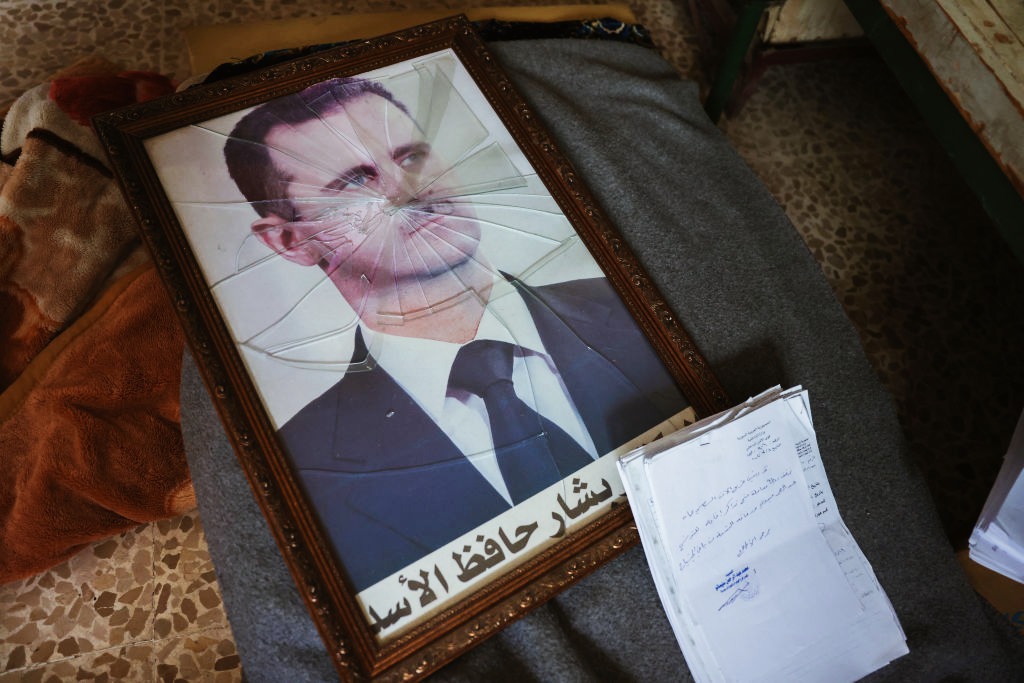

A momentous fortnight in the Levant. Following a negotiated ceasefire agreed in between Israel and Hezbollah bringing a fragile possibility of peace to Lebanon, opposition forces in Syria drove the dictator Bashar al Assad into exile. They ended 54 years of autocratic rule by the Assad family and 14 years of acute suffering for the Syrian people since the uprising of the so–called ‘Arab spring’.

Syrian Army soldiers not only abandoned their posts but also dumped their uniforms – though apparently not their guns – and thousands fled across the border to Iraq to avoid retribution. Around the world in countries that have given refuge to Syrian refugees in recent years, including Sweden, the UK and capitals in the Middle East, celebratory demonstrations erupted.

It is not clear what happens next

A Sunni businessman from Damascus proclaimed yesterday that he was now ‘living in a free Syria’, though such euphoria may unfortunately prove misplaced. Some of the opposition forces that took Aleppo, Hama, Homs and then Damascus in short order as the Syrian army melted away have an unsavoury track record. Hay’at Tahrir al Sham – already labelled ‘HTS’ by the vox pop – are listed as a terrorist organisation by the United Nations and its origins were as an affiliate of al Qaeda. Their leader, Abu Mohammed al-Jolani, who has gone from being an obscure resistance figure in the north-east of the country to global prominence in the space of a few days, repositioned the group in 2016 and distanced it from the global jihad movement to focus on the internal Syrian struggle. Those supporting the Assad regime maintain that HTS are terrorists.

This weekend, I listened to Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov tell a packed auditorium of international diplomats, politicians, academics and commentators at the Doha Forum that it was ‘inadmissible to allow terrorist groups to take control in defiance of agreements made by the Astana Forum’. He had just met with his Iranian and Turkish counterparts, the other main protagonists of that Astana Forum, to try and exert some sort of control over what is happening in Syria. Their joint statement reiterated the importance of respecting the sovereignty and territorial integrity of Syria, called for the end of hostilities, cited UN Security Council Resolution 2254 and demanded that it be fully implemented with dialogue between the government and opposition. The ink was barely dry on that statement when it appeared to be at least in part obsolete; Damascus fell and the opposition forces took full control.

It is not clear what happens next. Apparently, the Turkish government were aware of the opposition forces’ plans and in October stopped an offensive being launched. Russian forces were also seemingly aware of what might be afoot as they bombed the opposition forces’ bases heavily for a few days at that time. Not long ago, some countries took the now embarrassing decision to rehabilitate the Assad regime. Under Saudi and Emirati leadership, the Arab League allowed Syria to rejoin. And some European countries also re-established links which no doubt they now deeply regret. Others, such as the United States, United Kingdom and Qatar, retained their staunch opposition to the Assad regime.

Whatever happens next in Syria and whoever emerges as the power broker – they may not turn out to be much of an improvement on the Assad regime – the implications of what has just happened could prove profound and should be seen in the wider regional context. In particular, how the fall of Assad affects the fortunes of his two main backers could determine whether the Middle East now moves towards a more stable and prosperous period or descends into further conflict and instability. It was notable that Iran chose not to invest heavily in defending Assad’s position and that the Russians, while providing air support to the Syrian army also failed to intervene with the force that might have been expected.

Iran, which this year has been in direct conflict with Israel, seems to have calculated that it could not afford to be drawn in further to the battles in Syria this week. That has meant a withdrawal of IRGC forces from Syria. A big blow to Tehran is the loss of the supply route for Lebanese Hezbollah that has allowed that terrorist organisation – the jewel among Iran’s proxies – to become so strong and well-armed over the past decade. In signing the very recent ceasefire in Lebanon, Hezbollah and Iran appeared to have decided it was better to live to fight another day and plan to rebuild Hezbollah, rather than see it further degraded by Israel.

That goal would now appear much harder to achieve. The Islamic Republic faces the humiliation of having failed to defend its key ally, which will suggest to many Iranians that the regime is now weaker than in a long time. That will compound the difficulties that the Supreme Leader Khamenei and Revolutionary Guard leaders were already wrestling with, such as to how to respond to the last Israeli strikes on its air defences and concerned that further attacks – including potentially on vital oil installations and even nuclear facilities – might follow in the coming weeks.

Russia, despite Lavrov’s characteristic diplomatic bravado in Doha, is also faced with a dilemma. Since 2014, for the first time since 1967, Russia has had boots on the ground in the Middle East. It established bases on the Mediterranean for its navy and air force. That forward bridgehead has allowed Russia to grow its influence and project military might into the region in a new way. President Putin must now decide whether to relinquish those bases, particularly the naval port at Tartus, or to seek to maintain them in some way, whether through force or negotiation as the dust settles on the fall of Damascus.

Russia, despite Lavrov’s characteristic diplomatic bravado in Doha, is also faced with a dilemma

The positions of Turkey and Israel will have significant bearing on what happens next. The Turks arguably have the greatest influence over some of the forces that have ejected Assad. Israel, meanwhile, is still prosecuting its war on Hamas in Gaza and may be tempted to exploit the security vacuum in its neighbour Syria. There are reports already of Israel having pushed forward to occupy the Syrian slopes of the Golan Heights, which would prevent Syrian or others’ attacks launched from that high ground into Israel. While that clearly makes military sense, it would appear to be a blatant annexation of another country’s internationally recognised territory. Jordan may also continue to play an important role in the Syrian drama. Some of the Syrian opposition forces, such as the Southern Operations Room, have moved from near the Jordanian border to Damascus.

It is probably not a coincidence that these dramatic shifts in the political and security dynamics of the region are taking place against the background of an incoming US president, who has made clear his desire for the wars in the region to stop sooner rather than later. That may offer a further opportunity and encouragement for those seeking a regional grand bargain bringing greater stability. However, while the historical drivers of much instability in the region remain unresolved – such as the lack of progress towards a sovereign Palestinian state, as enshrined in UN Security Council Resolutions – the risk of further escalation and spreading conflict remains significant. Indeed, Prime Minister Netanyahu said as much when commenting cautiously on the fall of the Assad regime. As one Lebanese commentator told me, ‘the glass is half full but there is no room for complacency’.

Comments