John Bellingham dressed fastidiously. On the day that he committed murder, he wore exactly what the fashion magazine Le Beau Monde advised for a gentleman’s morning wear in 1812 — a chocolate broadcloth coat, clay-coloured denim breeches and calf-length boots, the whole set off by a waspish black-and-yellow waistcoat. By contrast, his victim, clad in the equivalent of a business suit — blue coat and dark twill trousers — was almost anonymous.

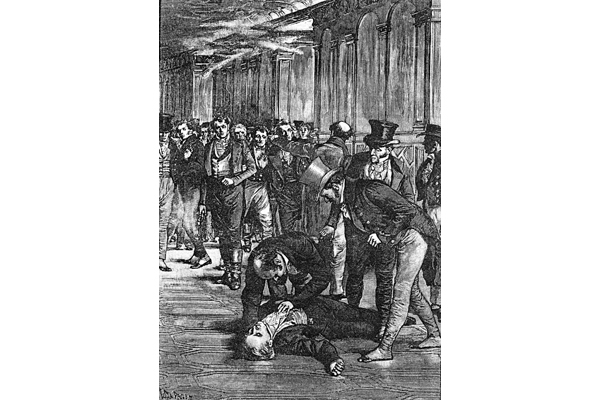

But Spencer Perceval had no need for display. Not only was he prime minister and chancellor of the exchequer, but, thanks to the insanity of George III and the loyal support of a majority of MPs, he had achieved a unique degree of political power. And when Bellingham confronted him in the lobby of the House of Commons on Monday 11 May, and fired a bullet into his chest from close range, Perceval also experienced the unique distinction of becoming the only British prime minister in history to be assassinated.

Other than an occasional reference in footnotes and pub quizzes, this startling crime has passed into oblivion, dismissed as the act of a lone gunman who, although generally thought to be ‘deranged’, was quickly tried, found guilty and hanged on the Monday following the murder. More surprisingly, Perceval also disappeared from view, remembered only by specialist historians for his ferocious oppression of the Luddites — he made it a capital offence to break a machine — Catholics, and political reformers. Yet for a democracy that since 2001 has cocooned its political leaders in security for fear of assassination, the circumstances of a prime minister’s murder should be of consuming interest.

It might also be of concern to David Cameron’s minders that, contrary to history’s judgment, the killing was almost certainly not the aberrant act of a single madman. One small clue comes from the expense of Bellingham’s dandyish tastes. A Liverpool merchant, the murderer had arrived in London on 2 January 1812, ostensibly to get compensation from the government for a failed business deal. In the next four months, he managed to spend at least £90 on comfortable lodgings, pistols and stylish clothes — a sum that would have paid the salary of a grammar school headmaster for 18 months. The weekly laundry bills for his extensive wardrobe were alone more than a labourer earned. Yet at his trial, he described himself as virtually destitute, ‘driven into tribulation and want … [and] my wife and child claiming support’. It is not unreasonable to wonder where the money came from.

The answer must begin with Perceval. The prime minister took power in 1809, and showed himself to be that dangerous phenomenon, a conviction politician whose policies were grounded in a belief that he wielded power as an agent of Providence. Thus he saw the war against Napoleon, not simply in military terms, but, like Reagan faced with the Soviet Union, as a war against evil. Perceval, however, identified France in biblical terms as ‘the woman who rides upon the beast, who is drunk with the blood of the saints, the mother of harlots’, which went beyond anything Reagan said about the communists.

The prime minister employed the same fundamentalist zeal against all his foes, and they responded in kind, one of them, the journalist William Cobbett, depicting him in a sharp phrase as ‘a short, spare, pale-faced, hard, keen, sour-looking man’. But Perceval was not without redeeming features: fortified by Bible prophecy, he kept Wellington’s army in the Peninsular War against all military and financial advice; in an era when harsh discipline was thought essential to a child’s upbringing, his indulgent affection for his children provoked Sydney Smith to the barbed comment, ‘If public and private virtues must always be incompatible, I should prefer that he … whipped his boys, and saved his country’; finally, and most significantly for his eventual end, he was unrelenting in his hatred of slavery.

In 2007, the bicentenary of the act making the slave trade illegal celebrated William Wilberforce’s role in the successful campaign. But it is one thing to pass a law, another to enforce it, especially when the illicit practice produces annual returns of £3 million, approximately £300 million today. Through orders passed in the Privy Council, Perceval turned the Royal Navy into an international police force, with the power under wartime regulations to enforce the ban by searching all vessels on the high seas; at the same time, his legislation made it a felony for British citizens to participate in the trade in any form and under any flag. At a stroke, many of the City’s grandees, including Barings bank, which financed the Brazilian slave trade, and the leading lights of Liverpool — Bambers, Gascoynes, Gladstones, and the like — whose ships operated under American and Portuguese flags, found themselves liable to imprisonment or transportation for up to 14 years. By 1812, the number of captured Africans shipped across the Atlantic had dropped by more than a third from the figure in 1807, a loss to the trade of £1 million. Murder has been committed for less.

When Perceval was shot, one London hostess wrote in her journal, ‘Nobody knows at present whether it was the sole act of this man, or whether it is a plot.’ The bitter hatred that the prime minister aroused, especially among Luddites and radicals, made conspiracy probable, and the authorities feared that the murder was the prelude to an organised revolution on the French model. When no uprising occurred, they — and historians ever since — concluded that there had been no plot either.

Yet it was the wealthy who had most to gain from Perceval’s removal from power and, given his political dominance, that outcome was unlikely to happen by parliamentary means — indeed, his successor would remain in office for almost 15 years. It is clear, too, from comments by a Liverpool newspaper that talk of assassination in the city was common. From Bellingham’s self-regarding, obsessive account of his motives — like Anders Breivik, he equated reality with his own toxic imagination — emerges the portrait of a twisted perfectionist who would make the ideal patsy. In his letters, personal records and the investigations of the Bow Street Runners, there is an unmistakable money trail leading from the City of London back to Bellingham’s home city of Liverpool, whose wealth was built on the slave trade. And by 1815, with enforcement relaxed under the premiership of Lord Liverpool, the illegal trade had bounced back, regaining £600,000 of its loss.

Cameron’s minders may have more to fear from the bankers than from al-Qa’eda.

Andro Linklater’s Why Spencer Perceval Had to Die will be published by Bloomsbury on 10 May.

Comments