On a freezing January morning two years ago, I joined a US army assault in an al-Qa’eda-controlled village in northern Iraq. We were dropped by helicopter half a mile from the village not long after midnight and shivered till dawn, when the soldiers launched their assault. They met with no resistance and by late afternoon had completed their searches and were mostly asleep.

I sat in the garden of the makeshift company HQ — the largest house in the village, commandeered from a reluctant sheikh. Above me a US soldier was on sentry duty, while at the bottom of the garden women were cleaning clothes in a stream. There was just enough warmth from the winter sun, so I took out my book, Sir Walter Scott’s Chronicles of the Canongate.

Like much of Scott’s work, it deals with the struggle between the clans of the Scottish Highlands and the savage British redcoats. The wonder of Scott is that he understood both sides.

His heart was with the clans because he loved their songs and customs and the contrast to the ordered life of an Edinburgh lawyer. But he knew that the old order was passing, that a new world was being born, and that, despite some atrocities, the British soldiers were not bad men. In Old Mortality, such a byword for cruelty as Graham of Claverhouse — notorious for the alleged murder of children and executing men without allowing them time to pray, let alone a trial — is portrayed as a figure of nobility.

The story I was reading concerned a murder committed by a young Highlands farmer travelling to England to sell cattle. He had been insulted and acted as his code of honour dictated, but found himself in a fatal conflict with modern notions of fairness and justice. All of Scott’s Waverley novels explore this confusion of sensibilities, set in motion by the Hanoverian succession and the birth of the British state at the start of the 18th century.

Scott, though some critics look down on him, is one of Britain’s greatest novelists, with an ability to evoke character matched only by Charles Dickens, and a tragic sense of men trapped in circumstances they cannot comprehend. He was the first great writer to brood at length on the conflict between modernity and the pre-industrial order — and this makes his books stunningly relevant today.

The struggle of the United States and its allies against Islamic insurgents in Iraq, Afghanistan and other parts of the globe is in essential respects identical to the battle between the British redcoats and the Scottish Highlanders of the 18th century. One side believes that it represents enlightenment and progress, the other side that it has no choice but to stand up for its liberties, beliefs and practices. Both sides regard their opponents as barbarous. We are talking about two ways of understanding family, community, ethics, religion, the state and mankind.

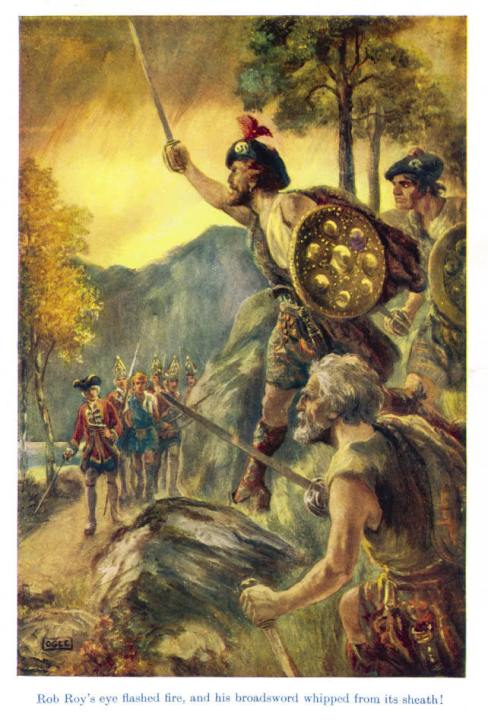

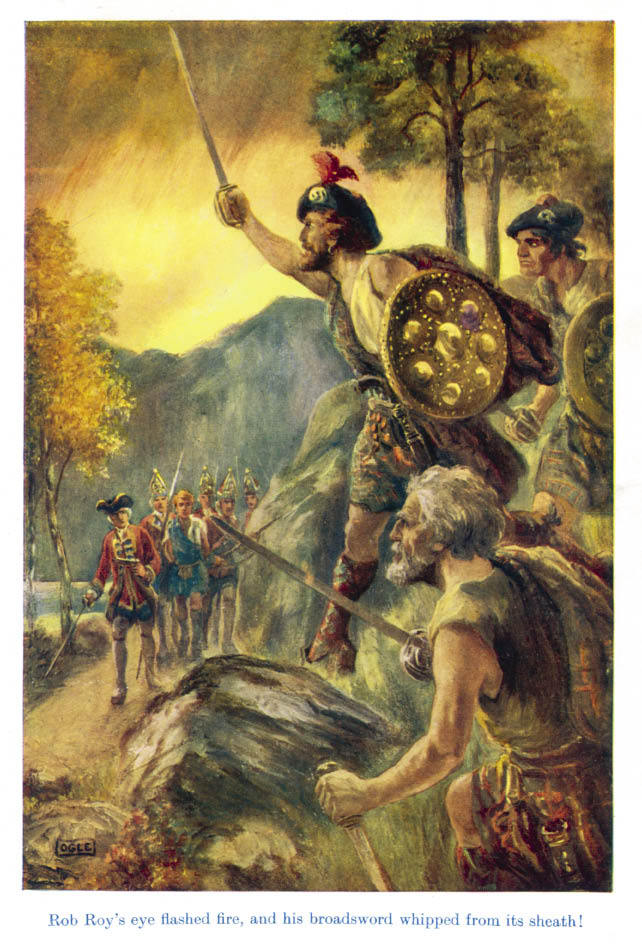

There are numerous lessons to be learnt from Scott’s novels. The first is that, though an unusually moral writer, he does not take sides. He writes with a profound admiration for the Highlanders who fought hopelessly for their way of life in the 18th century: characters such as Baron Bradwardine, Callum Beg, Rob Roy and Fergus Mac-Ivor were manifestations of an ancient culture in certain respects richer than the commercial society being established in their place.

For this reason, Scott stands in sharp contrast to the generation that immediately preceded him. When Boswell and Johnson made their journey to the Scottish Highlands in the 1770s, they could perceive little more than ignorance and squalor. Their contemporaries Voltaire, Gibbon, Hume and the other great writers of the Enlightenment celebrated the triumph of human reason over what they saw as barbarism and superstition. They had as little time for Highland clans as for Irish peasants, Tasmanians, Red Indians or black Africans.

Growing up in Edinburgh in the 1780s, Scott entered the same intellectual universe as Hume and Adam Smith. But he also spent his holidays at a family farm on the Scottish Borders. Above the farm was a keep where Borderers had taken refuge against raiders since time immemorial. He discovered family connections with the rebels against Hanoverian rule. As a trainee lawyer in Edinburgh he would spend holidays travelling through the borders and collecting Scottish ballads, the foundation for his first published work, The Lay of the Last Minstrel.

It is curious that at exactly the same time that Scott was making his way as a writer, the remarkable Mountstuart Elphinstone, also brought up in Edinburgh and a family acquaintance of his, was dispatched on the first British diplomatic mission to India’s North-West Frontier. Upon arrival, Elphinstone was at once reminded of the feuds and alliances of ancient Scotland — and, perhaps as a consequence, admired the Pashtun tribesmen: ‘Their vices are revenge, envy, avarice, rapacity and obstinacy; on the other hand they are fond of liberty, faithful to their friends, kind to their dependants, hospitable, brave, hardy, frugal, laborious and prudent.’ Elphinstone noted that they were always ‘ready to defend their rugged country against a tyrant’. He might just as well have been describing Scott’s Highlanders.

One problem with the ‘war on terror’ as prosecuted by the US and Britain is that both countries have tended to rely on the certainties of the Enlightenment rather than the more complicated vision which, thanks to Sir Walter Scott, Elphinstone and others, partially replaced it at the start of 19th century.

This observation does not just apply to policymakers. Our most influential novelists tend to accept a binary opposition between a virtuous western ascendancy and its hate-filled, barbaric opponents. Try Ian McEwan: ‘I myself despise Islamism, because it wants to create a society that I detest, based on religious belief, on a text, on lack of freedom for women, intolerance towards homosexuality and so on — we know it well.’

Scott was less ready to categorise and to condemn. I have little doubt what he would have made of today’s war in Afghanistan. He would certainly have celebrated the valour, integrity and honour of the British fighting men. But he would also have been an admirer of their Taleban and al-Qa’eda opponents, hiding out in caves, sustained by their religion, able to rely on the ancient codes of the Pashtun tribes for protection. Scott would surely have made a hero of Mullah Omar, the founder of the Taleban, who according to legend gouged out his eye and sewed up his eyelid when hit by a piece of shrapnel, and who now directs the war against President Karzai. He would have fully appreciated, and converted into great literature, the tragic conflict of loyalties felt by Muslims torn between support for the Islamic fighters in Iraq or Afghanistan and their British identity.

Anjem Choudary of the now proscribed al-Muhajiroun would have engaged Sir Walter. Choudary is an archetypally British fanatic with literary antecedents in Scott’s deranged Covenanter Habakkuk Mucklewrath in Old Mortality or the Gifted Gilfillan in Waverley. Scott might have acknowledged that Choudary was not always wrong. His plan to carry empty coffins, symbolising dead Afghan Muslims, through Wootton Bassett was tasteless and offensive to the families of dead British soldiers. But he was surely right to point out that Britain must acknowledge the thousands of Afghans, many innocent, killed as a result of allied military action.

Scott’s clans were excised from history after the 1715 and 1745 rebellions. The techniques that in barely 50 years converted the Highlands from an existential threat to the nascent British state to a sporting paradise for the Anglo-Scottish aristocracy are of extreme interest today. Some rebels were incorporated into the royal armies through the foundation of regiments which recruited from the defeated clans, above all the Black Watch, which has seen heroic service in Iraq and (in its regrettable new identity as the Royal Regiment of Scotland) in Afghanistan. This is comparable to ‘Afghanisation’: the attempt, so far unsuccessful, to build up a national army capable of defending a central state.

The second part of the British strategy in the Highlands was bribery, also much in use by occupying forces in 21st-century Afghanistan. In Scotland, clan leaders were paid significant sums to change sides. The Dukes of Argyll received more than £20,000, then a prodigious amount, to reinforce their wavering allegiance to the Hanoverians. Chiefs who refused to buckle were hunted down.

The third part of the strategy would today be called modernisation. The Scottish Highlands had enjoyed the same legally privileged status as Pakistan’s Federally Administered Tribal Areas, which harbour so many al-Qa’eda and Taleban leaders, including (it is believed) Osama bin Laden. The 1747 Abolition of Heritable Jurisdictions Act put paid to that, removing the right of local leaders to personally maintain the rule of law (including the power of ‘pit and gallows’). Another law ordered that all weapons should be handed in and banned Highland dress, particularly tartan, except as British Army uniform. From 1725 onward General Wade opened up the Highlands by building roads and bridges, many of which are still in use.

Finally, the British adopted a policy of what today would be called ethnic cleansing. After the Battle of Culloden in the spring of 1746, the Duke of Cumberland told his troops to give ‘no quarter’ to the vanquished Jacobite forces, opening the way to indiscriminate rape and killings. The decades that followed saw the Highland clearances, with the eradication of the economic and social structures that supported the clan system, imposed agricultural ‘improvements’, and the near-total depopulation of the Highlands, which never fully recovered. Some clansmen fled to the lowlands, but thousands sailed to America, where two decades later some took revenge on the British by joining the War of Independence.

This tactic has been applied in the tribal areas of Pakistan. Sanctioned by Britain and America, and armed with F16 fighters and lethal long-range cannon, backed up by helicopter gunships, the Pakistani army has maimed and slaughtered tens of thousands of tribespeople, the majority innocent of any involvement with the Taleban. In their hundreds of thousands they have fled their villages to camps and to relatives in the rest of Pakistan — a huge internal displacement that has scarcely been reported in Britain and America. But unlike Sir Walter Scott’s Highlanders, these Pashtun tribespeople have nowhere else to go and in due course they must return to their homes and resume their ancient way of life.

Comments