I am sure I have posed more questions to the chess engine Stockfish than to any living being. I love the instant gratification: you give it a chess position and it gives you an answer: the best move and an evaluation measured in hundredths of a pawn, like +1 24. Leave it alone, it will delve deeper; move a piece, it will respond anew. In human terms, ‘Ooh, a smidgen better for White’ gives way to ‘Go there, and your rook gets blown away’. The chess engine is, by turns, a spirit level and a hurricane forecast.

The basic design of a traditional chess engine like Stockfish is simple: check all the moves, back and forth, for both sides, and tot up the value of the pieces in each scenario. Then choose a move accordingly. But the tree of possibilities is so vast, even for a computer, that you must prune it judiciously: ignore the moves that blunder a queen, but not the brilliant sacrifices that lead to checkmate. Evaluating the pieces is nuanced as well. In the middlegame, you want mighty centre pawns, but in the endgame, a nimble flank pawn could be better. And don’t be too clever! If the evaluations are too sophisticated, they will take more nanoseconds to compute, so you won’t be able to examine as many positions.

Deep Blue, which narrowly beat Garry Kasparov in 1997, is a minnow next to the Stockfish of 2020, which is not just down to improvements in hardware. The powerful blend of algorithms and parameters that comprise Stockfish has been long in the making. An initial version was derived from a program called Glaurung in 2008, written by Tord Romstad. The latest version, Stockfish 11, credits Marco Costalba, Joona Kiiski and Gary Linscott alongside him. Crucially, Stockfish is freely available, open source software, so anyone can experiment with it. But how to begin tweaking something so complex? An important breakthrough came in 2013, when the ‘Fishtest’ framework was developed. Just as the Folding@home project allows users worldwide to run software which simulates protein folding for biological research, ‘Fishtest’ ensures that refinements to Stockfish are battle-tested over thousands of games on users’ computers, and only the best ones make it in.

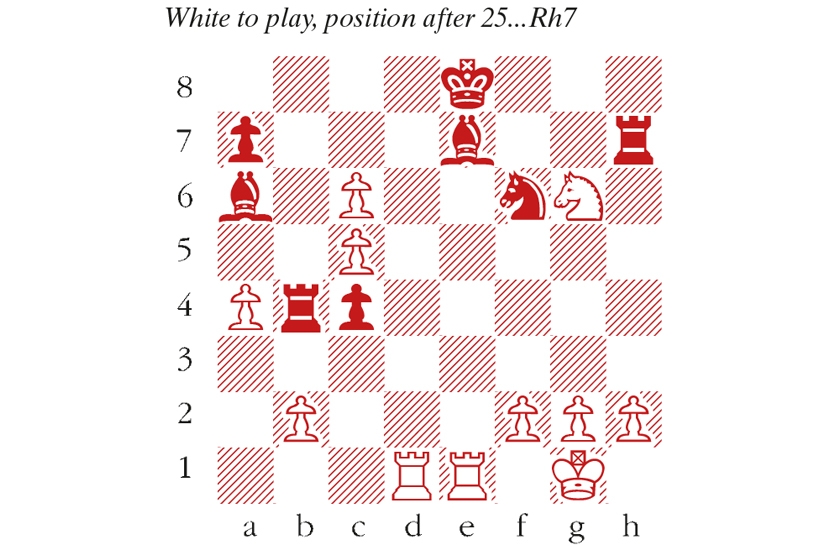

You can’t argue with the results: Stockfish just keeps getting better. Since 2013, it has finished first or second in every season of TCEC (Top Chess Engine Championship). The latest season saw Stockfish win the final against Leela Chess Zero, whose novel ‘neural net’ design, in contrast to Stockfish, is based on that of DeepMind’s famous AlphaZero. The eighth game was stupendously vibrant. In the diagram, Stockfish is two bishops for five pawns (!) down, but 26 Rd6!! emanates force. The f6 knight is attacked due to a pin, but the key point is that 26… Ng8 27 c7! Bb7 28 Rd8+ Kf7 29 Rb8! and White will ram the c7-pawn through. Note also the finesse 29 Rf6! which threatens Rf6-f8 mate. If 29… Rf7 30 Rxe7+! Rxe7 31 Rf8 mate.

Stockfish–Leela Chess Zero

TCEC Season 18, Game 8, June 2020

1 d4 d5 2 c4 c6 3 Nf3 e6 4 Nc3 dxc4 5 Bg5 f6 6 Bd2 b5 7 a4 b4 8 Ne4 f5 9 Ng3 Nf6 10 e3 Ba6 11 Be2 c5 12 dxc5 Nbd7 13 c6 Nc5 14 Nd4 f4 15 Nh5 Nfe4 16 O-O e5 17 Bxb4 exd4 18 Nxf4 Rb8 19 exd4 Rxb4 20 Re1 Be7 21. Bh5+ g6 22 dxc5 Qxd1 23 Raxd1 Nf6 24 Bxg6+ hxg6 25 Nxg6 Rh7 (see diagram) 26 Rd6!! Ne4 27 Rxe4 Rxb2 28 h3 c3 29 Rf6! Kd8 30 Nxe7 Rxe7 31 Rf8+ Kc7 32 Rxe7+ Kxc6 33 Rf6+ Kd5 34 Re3 Rb1+ 35 Kh2 c2 36 Rc3 Bd3 37 Rd6+ Ke4 38 Rdxd3 c1=Q 39 Rxc1 Rxc1 40 Rd7 a5 41 Rf7 Rxc5 42 g4 Kd5 Black resigns

Comments