In Margaret: Death of a Revolutionary (Channel 4, Saturday) — Martin Durkin’s superb tribute to our greatest prime minister — there was some footage of Harold Macmillan giving his ‘selling the family silver’ speech that made me quite sick.

What nauseated me first was the sycophantic laughter from his black-tie Tory Reform Group audience oozing entitlement at some smoky St James’s club; and, second, the noisome cultural assumptions behind Mac’s ineffably grand remark. According to Mac’s Weltanschauung, it was not only right that people of his class should always keep hold of their silver, their Canalettos and Rembrandts, but that everyone else, a notch or two below, should also applaud them for doing so. ‘Gor blimey, Lord Stockton, you’re a right proper gent and no mistake.’

Hand in hand with this — and you can see why so many of his breed were drawn to Oswald Mosley — went Macmillan’s upper-class national socialist view that the best way to run Britain was as a cosy stitch-up between the landed élite and the licensed corporate stuffed shirts supervising the managed decline of the nationalised industries. Up until 1979, Britain was a fascist state where the trains didn’t run on time and the amazing thing was, hardly anyone realised it.

One of the few who did — and they really were very few: mostly just Madsen Pirie and a handful of revolutionary, oiky whackos from the Adam Smith Institute and the Centre for Policy Studies — was a grocer’s daughter called Margaret Hilda Roberts. (You may have read a bit about her recently in the papers.) Young Margaret had read Hayek and knew what needed to be done. And she did it too — at the most terrible personal cost inflicted not so much by her enemies on the left as by her supposed allies on the ‘right’: the socialistic Tory wets of the Macmillan and Heath school to whom Cameron is the rightful true heir.

It’s not often you see a documentary that transforms the way you look at yourself and the world, but Durkin’s must-see masterpiece (still viewable on catch-up at More 4) had that effect on me. Though it presented its thesis as radical and counterintuitive — that Margaret Thatcher was no conservative but a working-class revolutionary — I’d say it made more sense than all the other Maggie tributes I’ve read put together.

Even now, people still don’t get it. Even now, the sophisticated line on Baroness Thatcher is that though she may have got one or two things right she was essentially a bossy vulgarian who lowered the tone, broke up ‘communities’ and established the culture of wanton selfishness that brought the global economy to the grisly pass in which it finds itself today.

So long as we go on thinking like this, we are never going to recover, for the way to engineer an economic revival is not to crush the lower orders’ spirit with welfare but to unleash it by getting big government out of their lives and giving them a real stake in their future. It’s bizarre, truly bizarre — 30 years after the Thatcher revolution which, as even David Cameron admits, saved Britain — that those of us who articulate the basic economic truths that made it possible are still as thin on the ground as were the Madsen Pirie revolutionaries of ’79.

And it’s inexcusable that so many on the left persist — as Kinnock did in the documentary — in endorsing exactly that same anti-Thatcher snobbery oozed by grandees like Macmillan, Jonathan Miller and the loathsome Alan Clark: that really it was quite wrong for the plebs to have too much cash because they’d only go and spend it on something dreadful like non-inherited furniture.

It’s that same poisonous ignorance, of course, which enables the left to rewrite other glorious moments in our history. Note, e.g., how the Industrial Revolution — which did even more to liberate the working classes from servitude than Maggie did — was recast at the Olympics opening ceremony as an ugly, grimy intrusion on Britain’s former pastoral idyll, with hideous tall chimney stacks bursting through our once green and pleasant land.

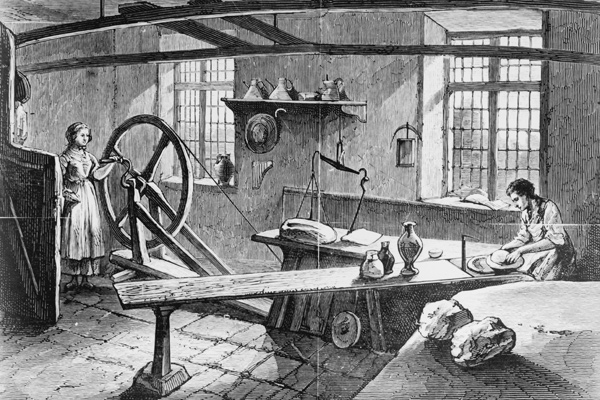

But as A.N. Wilson reminded us in his handsome tribute to The Genius of Josiah Wedgwood (BBC2, Friday) what these entrepreneurs really did was make the world a better place by giving more people more of what they wanted than at any time in history. Indeed, Wedgwood — though Wilson didn’t say this — was a revolutionary in the Thatcher mould. A fourth-generation potter, he transformed the family business by allying technological advances (new glazes, etc.) with a keen commercial insight into what it was that a newly affluent, increasingly sophisticated middle class wanted to have on its tea tables.

Besides all this, Wilson made the point, Wedgwood was a great philanthropist who believed that when you’ve made lots of money you have a moral duty to spend some of it on good causes. Well, I’d agree. But, as Thatcher understood better than any prime minister since: first you’ve got to make the money.

Comments