One of the many old temperance beliefs that linger on in the field of ‘public health’ is known as availability theory. Put simply, this theory says that if you make alcohol more available, people will drink more and there will be more alcohol-related problems. As a result, the temperance/public health lobby always wants shorter opening hours and fewer licences.

The problem with this theory is that it doesn’t stand up in the real world. More licences can correlate with more drinking for the obvious reason that more shops will sell alcohol in areas of high demand (public health campaigners struggle with the ‘demand’ part of ‘supply and demand’), but increased availability is neither a sufficient nor necessary cause of higher rates of consumption, let alone of alcohol-related harm.

And so, while the anti-booze brigade insists that licensing restrictions are needed if we are to tackle alcohol-related violence, the World Health Organisation admits that ‘there is a lack of clear evidence currently available on the impact of changes to permitted drinking hours on violence, with studies reporting contradictory results’. Among those contradictory results is the experience of England and Wales since the Licensing Act was introduced nearly 10 years ago.

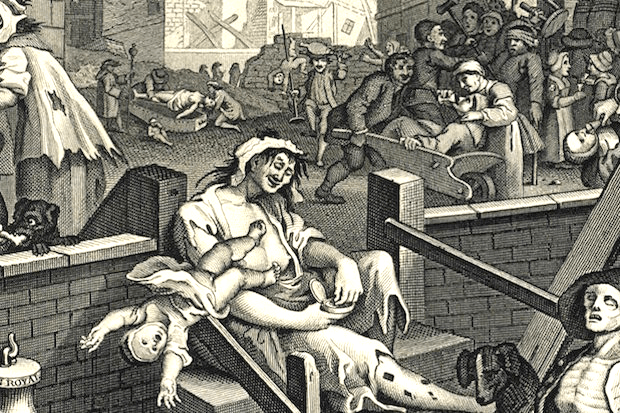

It is easy now to forget quite how fierce the opposition to relaxing the licensing laws was. You may not even know it as the Licensing Act, but as the ‘24-hour drinking’ law, since that is how much of the media referred to it.

Prophecies of doom were everywhere on the eve of its introduction. The Daily Mail predicted that ‘unbridled hedonism is precisely what the Licensing Act is about to unleash, with all the ghastly consequences that will follow’. The Sun told its readers to prepare for the ‘inevitable swarm of drunken youngsters’.

Scotland Yard predicted ‘an increase in the number of investigations of drink related crimes, such as rape, assault, homicide and domestic violence’. Prof Ian Gilmore of the Royal College of Physicians warned that ‘24 hour pub opening will lead to more excess and binge drinking, especially among young people.’ Everybody apart from Tony Blair and Tessa Jowell seemed to agree that the Licensing Act would bring nothing but trouble.

What happened next is the subject of a report I have written for the Institute of Economic Affairs. Published today, Drinking, Fast and Slow shows that since the Licensing Act came into force in November 2005, alcohol consumption has declined by 17 per cent and consumption in licensed premises has declined by 26 per cent. The proportion of young adults who say they drink frequently has fallen by more than two thirds. Rate of binge-drinking have fallen amongst every age group and rates of teetotalism are now higher amongst 16 to 24 year olds than they are amongst pensioners.

There has also been a 48 per cent decline in criminal damage, a nine per cent decline in public order offences, a 44 per cent decline in murder, and a 28 per cent decline in domestic violence. Despite a rapidly growing population, the number of violent crimes has declined by 35 per cent, according to the British Crime Survey, and by 17 per cent, according to police records.

As for health, there have been a number of studies looking at what happened to Accident and Emergency departments, most of which conclude that the Act’s introduction was associated with either a small decline or no change in the number of alcohol-related attendances. Meanwhile, alcohol-related mortality, which had been rising for years before the Act came in, started to level off in 2005 and has been essentially flat for the last ten years. There’s also been a decline in late night traffic accidents.

In short, every prediction made about the Licensing Act was wrong. Very wrong indeed. Contrary to the conventional wisdom, allowing us to drink for longer did not lead us to drink more. What happened instead is that we tended to go out later, stay out later and drink less.

There is no longer significant opposition to the new licensing regime. No parties mentioned it in their manifestos and there is no real pressure for the law to be repealed. The temperance/public health lobby has shifted most of its attention to the off-trade, where most of the alcohol in Britain is now sold. Those who still oppose the reforms rely on one of two arguments.

Firstly, they argue that the Act was a failure because it did not lead to the continental café-style drinking culture that was promised. Considering the British weather, this is hardly surprising, but the café culture aspect was never more than a bit of silly spin from the office of John Prescott. If you look at what the Labour front bench said at the time, it is clear that the main objectives were improving public order, diversifying the night-time economy and treating people like adults.

As Tony Blair said in January 2005, ‘We shouldn’t have to have restrictions that no other city in Europe has, just in order to do something for that tiny minority who abuse alcohol, who go out and fight and cause disturbances.’ This is not dissimilar to John Stuart Mill’s view of alcohol regulation, expressed 150 years earlier. As the Labour Party searches for a new way forward, it might reflect on the days when it won elections by sending text messages saying ‘Don’t give a XXXX for last orders? Vote Labour for extra time’.

Claiming that the Licensing Act was a failure because it didn’t achieve an unrealistic secondary objective is a way for the merchants of gloom to divert attention from their own dismal predictions. Their other argument is that the catastrophic effects of ‘24-hour drinking’ never materialised because pubs never opened 24 hours a day in practice. It is true that only a tiny handful of pubs have 24-hour licences and none them of them are used regularly, but the government neither hoped nor expected pubs to open all day and all night.

It was opponents of the reforms who painted a picture of endemic, round-the-clock bingeing. There was never any realistic prospect of this because there was never enough public demand to make it worthwhile for pubs to stay open all night.

Ten years later, most pubs still do not stay open until midnight, although most have the power to do so, because it does not make economic sense. On average, opening hours were extended by 27 minutes a day after the Licensing Act came in. This is not as trivial as it sounds – it amounts to an extra 13 million trading hours a year – but it is a far cry from round-the-clock boozing.

But, to repeat, it was the critics of the Licensing Act, not its supporters, who believed that the English were insatiable drinkers who were only restrained from permanent inebriation by restrictive licensing laws. This ‘24-hour drinking’ was their invention. In reality, deregulation led to pubs keeping sensible hours because most people want to drink at sensible times. It’s not a question of availability creating demand, as temperance dogma insists, but of demand creating availability – and demand is limited.

The scare about 24-hour drinking was a classic moral panic, as Henry Yeomans argued in an excellent academic study in 2009. When it was introduced, the Licensing Act made life a little bit better for millions of people without creating any of the terrible consequences that were forecast by the prophets of doom.

It would be nice to believe that the failed predictions of the past will make people more sceptical of the Chicken Littles next time the government suggests liberalising something, but that may be a forlorn hope and, besides, it’s a long time since a government has suggested liberalising anything.

Comments