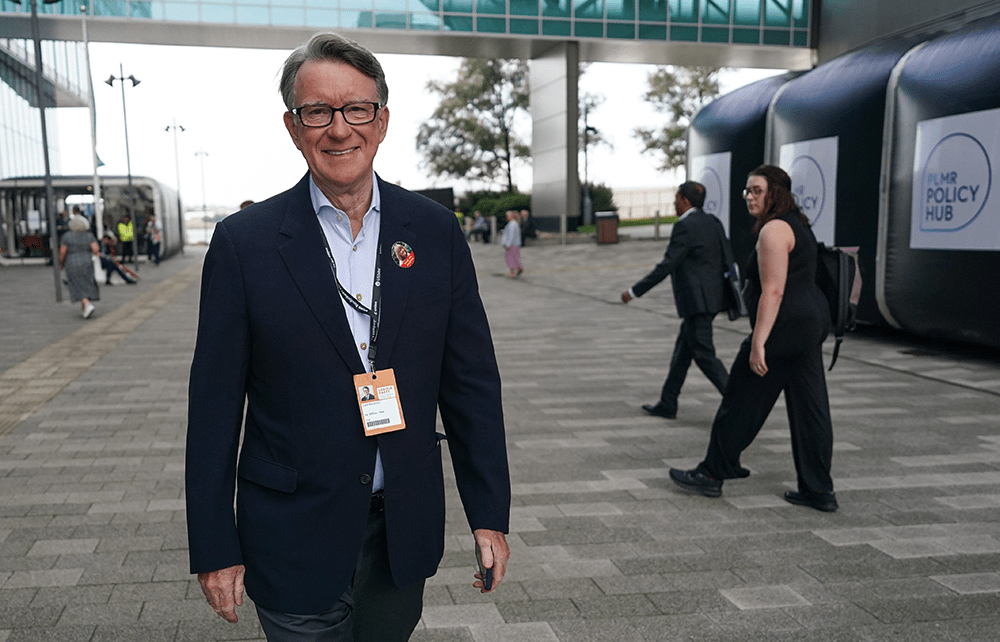

Being Cambridge, I thank God that we have no nonsense about electing our chancellor. We have had a blameless, unchallenged succession of eminent persons. Since 1900, three prime ministers (Balfour, Baldwin and Smuts), two military commanders, one royal Duke (Prince Philip), two great scientists (Lords Rayleigh and Adrian) and now that prince of commerce and philanthropy, Lord Sainsbury of Turville. Their presence has passed almost unnoticed, rightly so: a chancellor’s role is to be, not to do. Poor Oxford, however, has a form of democracy to choose its chancellor, and now has insanely extended its effective franchise by online voting. So there are 38 candidates, and pressure that they should stand for something or other, know how the university works and play a part in academic politics. If I had a vote, I would seek the candidate who stands for nothing at all. My eye would alight on probably the best-known, Lord Mandelson. He is brilliantly well-connected and therefore good at fund-raising, astute, tall enough to wear the robes with dignity and a connoisseur of la comédie humaine. There is an insuperable objection, however, which is that if Mandelson believes in anything, it is advancing the power of China. The Chinese Communist party is by far the richest and most corrupting single foreign contributor to our academic life – as Lord Patten, the outgoing Chancellor, has often warned. If you want China in charge, why not cut out the middle Mandelson and vote in Xi Jinping himself? He read chemical engineering at Tsinghua University as ‘a worker-peasant-soldier student’ and holds honorary degrees from King Saud University, St Petersburg University and the University of Johannesburg.

The cabinet secretary, Simon Case, has told all government ministers that the Assisted Dying Bill is an issue of conscience, not government policy, and so collective ministerial responsibility is set aside. That is correct. But it is the prime minister not the cabinet secretary who decides how ministers should approach issues of conscience. Mr Case added something else. Ministers, he said, ‘should not take part in public debate’ on assisted dying. That is not the convention. On capital punishment, for example, on which the Tories were for many years split, Margaret Thatcher, when prime minister, expressed her support in interviews, while permitting a free vote in parliament (which the opponents of capital punishment always won). As her home secretary, and therefore the relevant cabinet minister, Leon Brittan made a speech in parliament in which he supported capital punishment for terrorist killers only. The convention is not that ministers must be silent, but that they should make clear their view is strictly personal. Wes Streeting, the health secretary, says he will vote against the bill. Shabana Mahmood, the justice secretary, says her Muslim faith impels her to oppose it. Mr Case cannot silence them.

Labour has surely committed no crime by helping volunteers help the Harris campaign, though if I were an American voter, I might not welcome them. But it should recall what happened in 1992, when John Major’s Conservatives sent Mark Fulbrook to help George H.W. Bush’s campaign dig dirt on Bill Clinton. Clinton won, and consequently humiliated the Major government by giving Gerry Adams a visa to enter the United States. Lesson: pain without gain.

Near us in Sussex, two prep schools, Marlborough House and Vinehall, the latter formerly attended by our children, are amalgamating. It is a sadly logical reaction to Labour’s 20 per cent VAT on the fees. I hear other stories of closures and amalgamations, small prep schools being financially the weaker part of the sector. When, in more prosperous times, I was a governor of an independent school, I argued we should try to keep fees down because the market might break. We would then have to survive on the super-rich alone, which was not what such schools are for. They are there to help the many who seek the best for their children, not the few who can get it without effort. I think of all the musical, sporting, intellectual and dramatic talents unlocked by prep schools, of the many special needs children with whom the state system cannot cope, and of children with parents abroad, and I wonder how a Labour government thinks it is helping ‘working people’.

I had never attended a funeral with two coffins until I did so last week in St James’s, Piccadilly. That double presence has a solemn impact. The dead were Mike Lynch, the tech tycoon, and his 18-year-old daughter, Hannah, both of whom drowned in the freak storm which sank the family yacht off Palermo in August. Leading the cortege were Mike’s widow, Angela, their elder daughter, Esme, and two of the family dogs. Draped over Hannah’s coffin were words from the ‘personal statement’ which helped win her place at Oxford. She would have gone up this month. Her eloquent expression of her intellectual ambitions, now never to be fulfilled, was poignant, as were the pews filled by her female fellow pupils and the coffin carried by her male ones. I have read that personal statements may be abolished because, like everything requiring originality, they are now regarded as elitist. They should be kept. Hannah’s should be the model, encouraging pupils to write them with head and heart, as if they were their epitaphs.

Sometimes I tell people that when I was a boy we used to put our car on a plane and fly to France. Sometimes they do not believe me. Leafing through a 1959 Daily Telegraph this week, I found proof. ‘It’s cheaper to fly your car by Silver City’, said an advertisement, asking £5 to take a Ford Anglia to Le Touquet and £14 for a Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud. There, I didn’t dream it.

Comments