What is your p(doom)? This is the pseudo-scientific manner in which some people express the strength of their belief that an artificial superintelligence running on computers will, in the coming decades, kill all humans. If your p(doom) is 0.1, you think it 10 per cent likely. If your p(doom) is 0.9, you’re very confident it will happen.

Well, maybe ‘confident’ isn’t the word. Those who have a high p(doom) and seem otherwise intelligent argue that there’s no point in having children or planning much for the future because we are all going to die. One of the most prominent doomers, a combative autodidact and the author of Harry Potter fan-fiction named Eliezer Yudkowsky, was recently asked what advice he would give to young people. He replied: ‘Don’t expect a long life.’

Expressing such notions as probabilities between 0 and 1 makes them sound more rigorous, but assigning numerical likelihoods to one-off potential catastrophes is more like a game of blindfold darts: no one agrees on how such figures should be calculated. Just as no one actually knows how to build an artificial superintelligence or understands how one, if it were possible, would behave, despite reams of science-fictional argumentation by Yudkowsky and others. Everyone’s just guessing, and going off the vibes they get from interacting with the latest chatbot.

The AI doomers are the subject of too many chapters in Tom Ough’s book, which traces the career of one of their godfathers, the philosopher Nick Bostrom and his Future of Humanity Institute, a research unit latterly shut down by the University of Oxford. It also excitedly relates Rishi Sunak’s creation of the UK’s AI Safety Institute, which earlier this year was renamed the AI Security Institute when it was announced that the American AI company Anthropic would be helping the UK to ‘enhance public services’. Presumably the implication that AI might be unsafe was distasteful to the American corporation, currently valued at $100 billion.

Probably AI doomerism as a whole is just another millennarian apocalypse cult. No one mentioned here, at least, seems bothered by the harms that existing AI is causing – from destroying students’ ability to think to helping lawyers plead arguments with reference to made-up cases or decimating the creative class as a whole – inasmuch as what is called ‘AI’ is a set of giant plagiarism machines that are fed illegally acquired artwork and books and simply spit out probabilistically recombined copies of them.

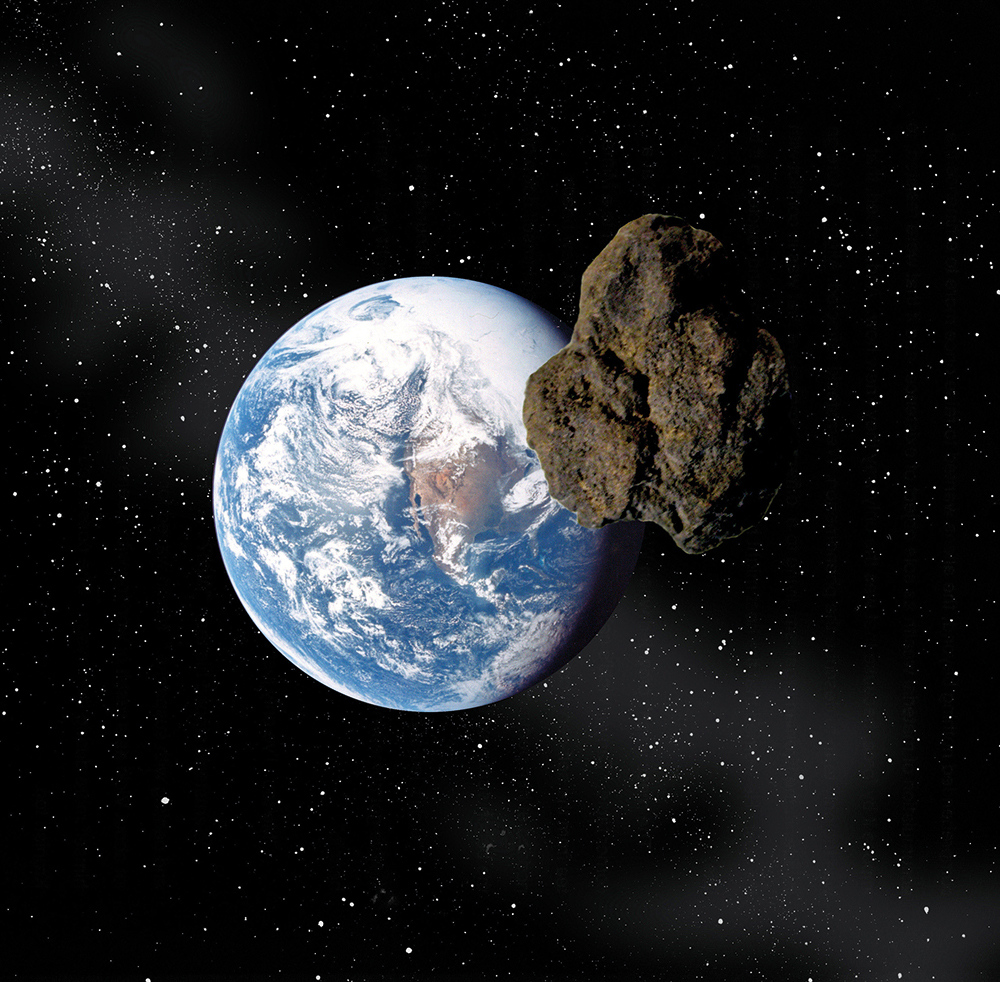

Much more dangerous in the real world are the other classes of ‘existential risk’ – catastrophes that could cause the extinction of the human race, or at least a very bad few decades for billions of people. What about an asteroid strike, for example? A space rock 10km across did for the dinosaurs, and over Earth’s long history the planet has, as Ough amusingly puts it, resembled ‘not so much an island paradise as a coconut shy’. So he talks to the scientists who successfully conducted the first asteroid-deflection experiment, when Nasa crashed a spacecraft into one named Dimorphos in 2022 and successfully altered its trajectory. Not as glamorous as sending Bruce Willis to nuke it but arguably more practical.

In 2022, Nasa crashed a spacecraft into an asteroid named Dimorphos and successfully altered its trajectory

Ough also talks to people worried about solar storms – a big enough coronal mass ejection could bring down power grids and electrical equipment over an entire hemisphere of Earth – and about supervolcanoes, which are like volcanoes but bigger and could cause something resembling a global nuclear winter lasting years. It turns out that there are even people working on ‘defusing’ volcanoes by drilling carefully into their magma chambers – though it is a bit worrying that only 30 per cent of the world’s active volcanoes are monitored for signs they might be getting ready to blow.

Other chapters consider nuclear war, and the potential for saving people in a real nuclear winter by converting the fungi that will flourish in such conditions into a mass food source; or the prospects for reversing some global warming by geoengineering – seeding the high atmosphere with sulphur particles that reflect sunlight. (This one might go wrong.) The dangers of biowarfare, meanwhile, have never really gone away. Indeed they are greater than ever, Ough argues, in a high-tech world of benchtop DNA synthesis of novel pathogens.

The conceit of this book is that all the men and women studying such risks are part of a global society of superhero boffins that the author names the ‘anti-catastrophe league’. And it would indeed be pleasing if they all worked together in a giant spaceship, like the Avengers. Ough’s style is at times misfiringly jokey (I don’t think anyone needs to be told that Hollywood is ‘that ever-reliable purveyor of public collective-consciousness epiphenomena’). But he writes with vim and colour about a lot of interesting subjects. My favourite chapter follows the people who are really interested in drilling extremely deep holes into the Earth, trying to beat the impressive record of the Soviets, who made a borehole 12km down. Do more of this and you’d have lots of cheap geothermal energy to power, er, more AI data centres.

So how worried should we be? After reading this entertainingly dark book, your p(doom) might be very low for the AI apocalypse but much higher for other kinds.

Comments