Easter is the most important festival of the Christian calendar, and so it is unsuprising that most of England’s Pre-Reformation churches were adorned with artworks commemorating Christ’s passion and resurrection. Sadly, such was the zeal of the reformation that virtually none of these depictions remain, apart from fragments, mutilated, burnt or eaten away by rot and woodworm. But it is still possible to see some remains of the pre-Reformation Easter in England’s oldest churches today.

The most common pre-Reformation Easter depiction in every church would have been an image of the Crucifixion over the Chancel arch, between the sacred space of the Chancel and the people’s part of the church, the Nave.

The so-called ‘Mostyn Christ’ in Bangor Cathedral shows the power that such a figure would have had over the faithful. Wearing his crown of thorns, Christ is seated in contemplation, a ‘man of sorrow’ just before his Crucifixion. His torso and the drape-covered rock he sits on is cut from a single oak, with a skull at his feet.

Many carvings of the Crucifixion were fixed into a lower carved piece that depicted Golgotha (also known as Calvary) with rocks bestrewn with skulls and bones that would have sat atop a Rood Screen that divided the Chancel and Nave. Only one such example survives, at St Andrew’s in Cullompton, Devon – and it is a mighty and gruesome artwork, hewn out of a single tree trunk in the fifteenth century and then cut into two sections the same width as the flamboyant late-fifteenth-century rood screen that still survives.

The most complete and, for many, moving remnants of a medieval English carved figure of the crucified Christ are the painted wooden head and foot from a 12th-century crucifixion at All Hallows, South Cerney, Gloucestershire. The figures are little more than painted gesso, a mix of chalk and glue obtained from rabbit skins. Beetles have eaten away at the wood.

I first encountered these fragments at an exhibition of medieval sculpture at Tate Britain in 2001. They were displayed in an illuminated cabinet, with a blank space between them where the rest of the figure would have been. Even as fragments, they still possessed great power. I noticed how museum visitors crossed themselves when they saw the two precious parts and understood that it still inspired devotion, which said something of their power to move people in medieval times.

Despite the gauntness of Christ’s foot, it is an object of touching beauty. Rendered in pale fleshy tones with a puncture hole where it was pierced by a nail, its angular toes are bent in agony. Christ’s head is so small that it could be held in cupped hands. His eyes are closed, delicate eyelashes rest on prominent cheekbones above a downturned mouth, and a drooping triangular moustache conveys a mysteriously calm repose.

English medieval churches have a furnishing that is unique to England, the Easter Sepulchre, also known as the Tomb of Christ. These recesses in the church wall were only used once a year, during the Easter celebrations.

Hawton in Nottinghamshire has one of the best Easter sepulchres. Three yards tall and a couple of yards wide, it is divided into three horizontal limestone sections, which tell the story of the Crucifixion and resurrection. The foliage that adorns its three canopies is thick with fruit and leaves that look wind-blown. These canopies cover a mutilated depiction of Christ as he steps from his tomb. Mary kneels by her resurrected son.

The top panel is dedicated to Christ’s ascension to heaven. Flanked by an angel choir, all that is now visible is the bottom of his funeral garment, and his feet can be glimpsed as they ascend through a canopy. Beneath, the 11 barefoot disciples look up into the clouds. The base is my favourite; each of its panels contains a crouched Roman soldier slumbering against his shield instead of guarding Christ’s tomb. They are clad in the garb of late fourteenth-century men-at-arms – chainmail and surcoat – as if they had just returned from the Hundred Years’ War.

At Easter time, the vessels which held the consecrated host in which Christ’s body and blood were believed to be present were left in the sepulchre recess on Good Friday. This would then become a temporary sacramental shrine during the Easter devotions that culminated in a vigil on Sunday morning. The villagers would have padded in barefoot to kiss the host. The cross would have been raised and processed around the church and Churchyard, accompanied by incense and bells to purify the air before they were placed on the altar to symbolise Christ’s Crucifixion and Resurrection.

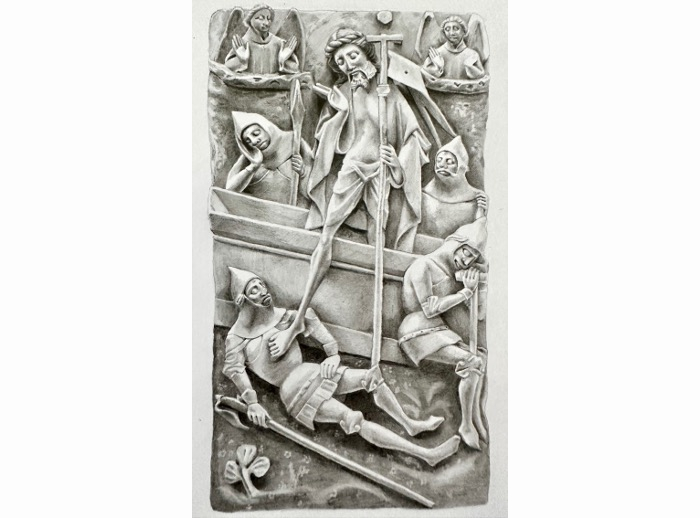

Depictions of Easter were also common in altarpieces known as Reredos, carved in translucent Alabaster from Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire. The image below depicts the Resurrection; Jesus lifts one near-skeletal leg over the side of the tomb and gently puts a foot down on a moustachioed sleeping guard to avoid waking him in a way similar to those carved into Easter sepulchres. The risen Christ is so exquisitely rendered that his shroud looks like it will yield if it is so much as touched.

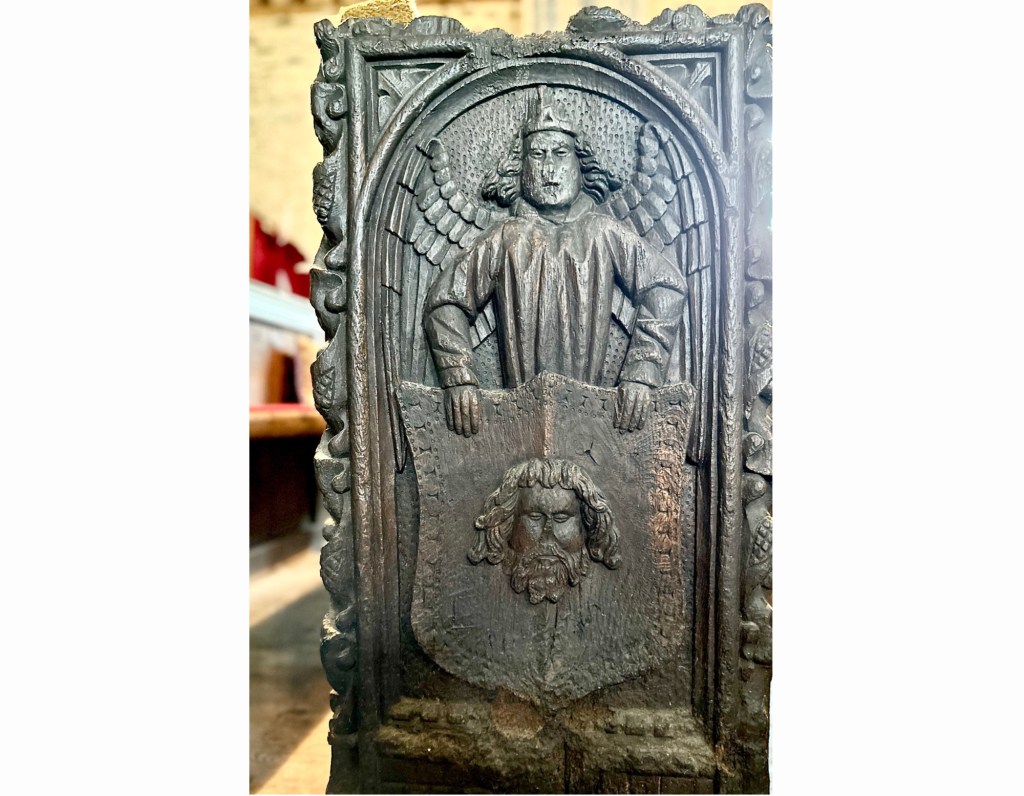

At St Nonna’s in Altarnun, Cornwall, the Tudor bench ends are carved with images whichwere subsequently prescribed during the Reformation, such asone showing Christ’s five wounds (from the nails in the cross and the Holy Lance) which was a subject of devotion in the Middle Ages. One of the benches features a portrait of Christ held on a handkerchief by an angel known as a ‘vernicle’. It is an image that St Veronica caught when she wiped the face of Christ on his way to the cross, causing his features to appear upon the cloth miraculously.

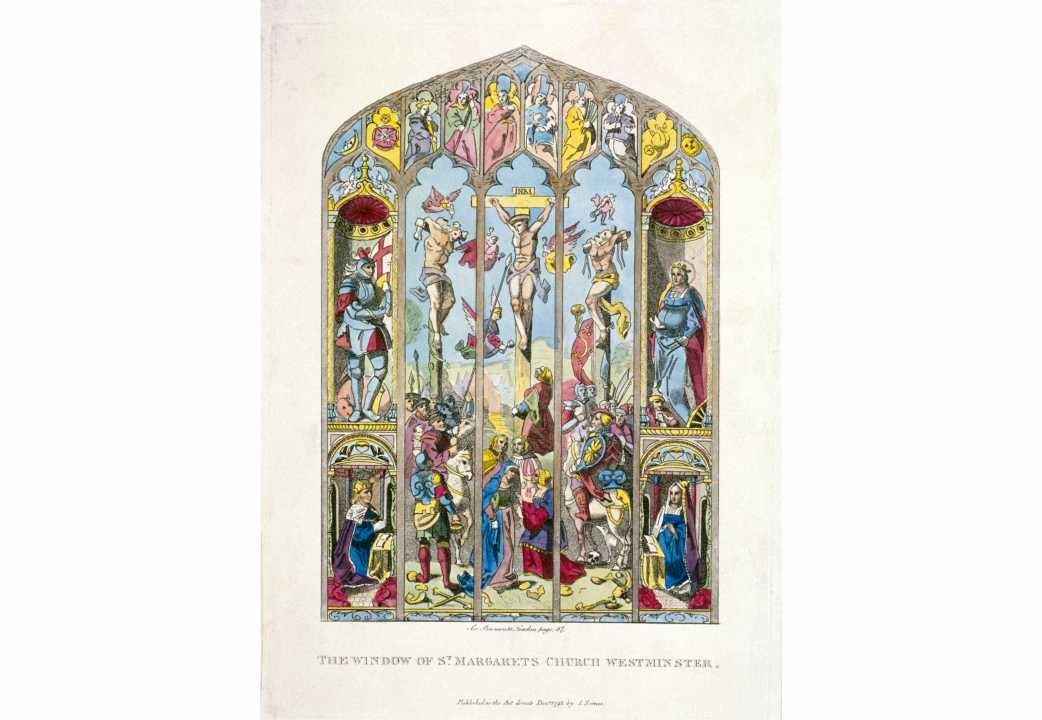

It is surprising that the iconoclasts missed these images in St Nonna’s. Even more surprising is the survival of an artwork which can be seen at the ground zero of the English Reformation at St Margaret’s, Westminster. The church’s great east window, illustrated at the top of this article, contains an unharmed and complete depictionof the Crucifixion in the most easily destroyed material, glass.

To add to the miracle of its survival the timing of its creation in 1526 could not have been worse. It commemorates King Henry VIII’s wedding in 1509 to Catherine of Aragon. The young married couple can be seen kneeling in prayer, separated physically from each other in the bottom corners. When the window was made Henry was already smitten with Anne Boleyn. I wonder who then would have imagined the destructive onslaught this would lead to when nearly all other depictions of the Crucifixion in painted glass, wood and stone were destroyed.

The plight of these artworks is a reminder of how incredibly fortunate we are that any pre-Reformation images and depictions remain. They are our connection, after all, to over a thousand years of Christianity in England.

Comments