To some extent, all Romanticism has its origins in darkness, coming in the wake of the 1755 Lisbon earthquake that introduced fear into the age of reason. ‘Reason’s Sleep Produces Monsters’ proclaims the opening drawing in Goya’s series ‘Los Caprichos’ (1797–99), which features in this entertaining exhibition. After all the cruelties that man had inflicted on man at the 18th century’s twilight, it was only natural to turn to ghosts and witches for light relief. The exhibition’s title comes from an Edgar Allan Poe story but Goya’s phrase would be equally appropriate.

The exhibition starts not with Goya but with F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922), one of those German expressionist films that so influenced early cinema: silent and in black and white. Nosferatu was based, without attribution, on Bram Stoker’s Dracula and another clip, this one from Bela Lugosi’s Hollywood Dracula, is one of the exhibition’s funniest moments. Romantics, with their penchant for gore and thunder, could tip over into unintentional absurdity — for example, in portraying Milton’s Lucifer as a Byronic hero, or in a gleeful Mephistopheles flying like a bat through the sky, as in Delacroix’s 1828 lithograph for Goethe’s Faust. Delacroix’s skill makes the subject work but in lesser hands it would not. Of course, laughter can be mixed with unease. John Martin’s majestic ‘Pandemonium’ (1841) from Paradise Lost is impressive, especially in its frame decorated with serpents; it was as well that Martin expressed his interest in hellfire on canvas rather than by imitating his brother, who tried to set fire to York Minster.

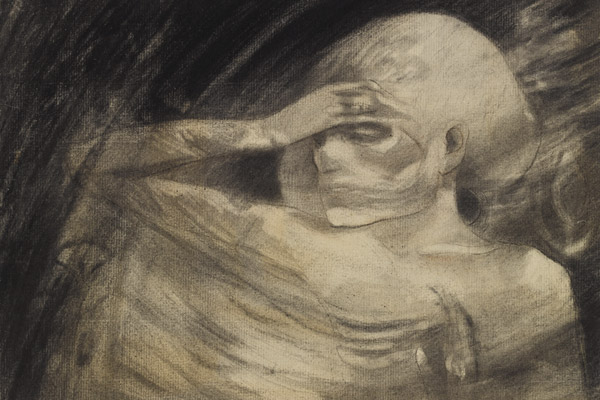

Horace Walpole thought Fuseli was mad and in the 20th century Sacheverell Sitwell detected evil in his work. ‘Mad Kate’ (1806–7), in Fuseli’s illustration for Cowper’s poem ‘The Task’ (to this eye reminiscent of Romney), does indeed look convincingly unhinged. Less distinguished is Fuseli’s ‘The Three Witches’ (1783), who might be Bottom and two of his mates having a lark with the Scottish play. His specialities were fear, sex and violence, the first two of which appear in ‘The Nightmare’ (1781), a painting that shocked and titillated Fuseli’s contemporaries with its abandoned sleeping beauty and a mischievous imp perched on her nightgowned lap. Nowadays it seems playful in comparison with Goya’s ‘Caprichos’ and ‘Witches’ Flight’ (1797–98), sardonic portrayals of man’s inhumanity.

After a lull, Dark Romanticism returned at the end of the 19th century in the form of Symbolism and then once more as Surrealism between the wars. By then, however, Lucifer had given way to the femme fatale, Salome or Medusa, or the Doomed Maiden Ophelia — deadlier than the male, perhaps, but much less given to carnage. Disappointing as it is to find that the French and German curators have neglected the Pre-Raphaelites and Beardsley, the final section is enticing. Perhaps it makes macabre sense that death should appear in a woman’s guise in Carlos Schwabe’s ‘The Death of the Gravedigger’ (1895), the 20th century’s curtain-raiser with snow falling everywhere. Gustave Moreau’s ‘La Débauche’ (1893–96) is so civilised that it longs to dice with barbarism, while William Degouve de Nuncques’s ‘Pink House’ (1892) is eerie in its ordinariness. In this way, the exhibition concludes less on a bang than with a satisfying shiver.

Comments