‘An old lady’s fallen down – quick! She’s bleeding. Come help.’ An elderly woman lay on the entrance steps of the block of mansion flats, food from a Tesco bag spilled around her, blood spreading on the stone. It was clear she’d tripped and banged her forehead, opening a large gash over her right eye. The courier had already tried to call an ambulance, but been put on hold. He had to continue his delivery run, so he’d begun ringing doorbells to summon assistance.

The lady was groggy but awake. I asked her name – Daphne. I helped her sit up, slowly, and propped her against the doorway’s cold brickwork. Checking she wouldn’t keel over, I ran inside for a box of tissues. We wadded up handfuls and pressed them on the wound to staunch the bleeding.

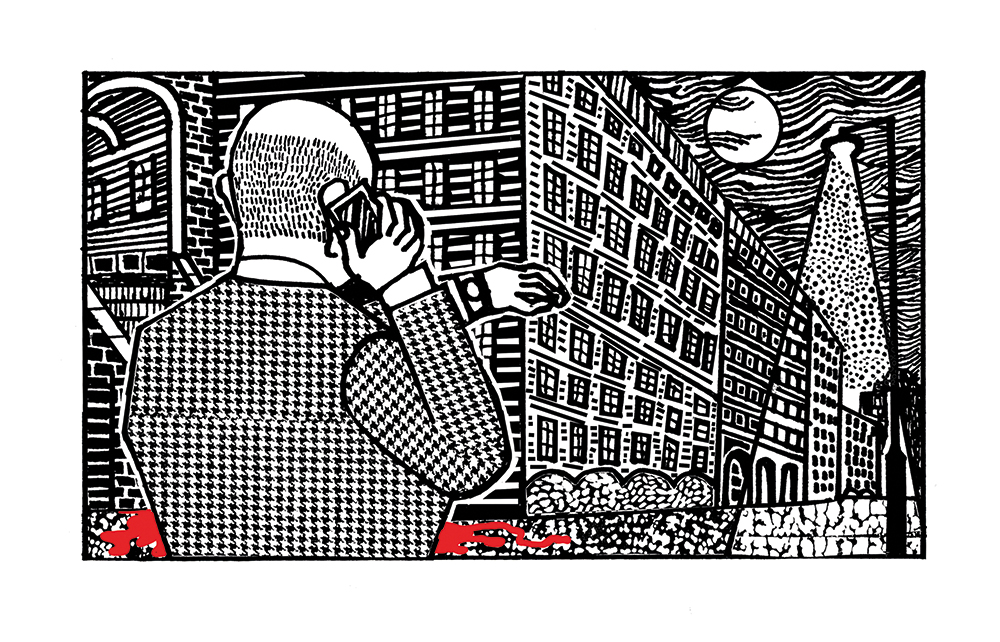

I dialled 999 and asked for the ambulance service. Like a fool, I believed that London actually still had one.

I dialled 999 and asked for the ambulance service. Like a fool, I believed London still had one

The operator came on the line in seconds – a hopeful sign. Or so I thought. Her questions were quick-fire and efficient: was the patient conscious? Yes; was she still bleeding? Yes; could she walk? No. Instructions on stopping the bleeding followed – clean tissues, pressure. So far, so good.

Then, our location. The operator wouldn’t log the address until she had the correct postcode. Though my mother lives in the block, I did not know it by heart and had to look through post in the hall. Next, the bureaucratic phase. The patient’s full name and date of birth (never an easy question to ask an elderly female stranger, least of all when she is close to fainting with pain and covered in blood). NHS number? By the time we got to this stage, I had been on the phone for 15 minutes, talking to the operator rather than tending to Daphne, who had begun to shiver.

‘When is the ambulance arriving?’ I asked several times in the course of this form-filling. ‘Is it on its way, at least?’ No response, except that the operator was going to ‘check with the dispatcher’. I was put on hold for five more minutes. Then, finally, an answer.

‘A paramedic will call you back within an hour,’ said the operator. I was incredulous.

‘She will have bled or frozen to death by then. We need an ambulance. Now!’

The operator repeated, word for word, her statement about the paramedic calling back. I repeated my response. We did this three times.

‘She’s welcome to make her own way to A&E,’ the operator finally offered.

‘But you told her not to try to move or stand?’

‘She’s welcome to make her own way to A&E,’ the operator repeated.

‘Perhaps you didn’t understand – there’s an elderly lady lying on the cold street bleeding and needs an ambulance urgently…’

‘A paramedic will call you back within an hour,’ repeated the operator, quickly, and then actually cut me off. We had been talking for 27 minutes.

At this point a young couple, passers-by, had stopped to help. I told them that there would be no ambulance, only a phone call. In an hour. The three of them looked at me, incredulous.

I’ve been a foreign correspondent all my life. I have not spent my career in a world of niceness and convenience. I’m usually good at getting stuff done in dysfunctional, chaotic, disaster-wrecked places – which more often than not consists of successfully persuading strangers to help. London Ambulance had defeated me. I felt embarrassed and at a loss. ‘Let me try again.’

When I dislocated my shoulder in Istanbul help arrived in 15 minutes. In London? It’s two-and-a-half hours

I called 999 once more. This time round I added urgency, drama, lurid details. We went through the same lengthy rigmarole identifying the patient, finding the address where she was (for the record – in Dolphin Square in Pimlico, a four-minute drive from St Thomas’ hospital). This time my histrionics – plus repeated and more insistent mentions of blood loss, danger of hypothermia, etc – seemed to do the trick. After a ten-minute wait on hold, the happy news came.

‘An ambulance is on its way,’ announced the operator – news that I relayed immediately to Daphne and our new young friends. ‘It will be with you within two-and-a-half hours.’

‘She could be dead in two-and-a-half hours!’

‘Your call has been assigned one of the highest priority classifications,’ responded the operator. ‘The ambulance may be with you sooner, but I must advise you that the call-out time for this type of emergency in central London is currently two-and-a-half hours.’

Over the next ten minutes I experienced one of the most Orwellian conversations of my life. Could Daphne be escalated to a higher priority?

‘An ambulance is on its way,’ answered the operator, repeating her spiel. I said that I’d heard and understood her clearly, no need to repeat. But an old lady was in a serious condition and needed to get to a hospital urgently. ‘An ambulance is on its way.’ The exact same words, again and in full. If this is high priority, how long do low-priority people have to wait? ‘An ambulance is on its way…’ And so on.

Nearly an hour had passed since I first called 999, 49 minutes of which I had spent on the line with London Ambulance. The young couple, shaking their heads in incredulity, summoned an Uber and volunteered to take Daphne to hospital themselves. I had a plane to catch and was running late. We parted in the dark as London drizzle began to wash Daphne’s blood from the doorstep.

I was just getting off the Gatwick Express when a call finally came through. It was 7.30 p.m., some two-and-a-half hours after the emergency had been called in. It was a paramedic. ‘Is the patient still in need of assistance?’ she asked. The ambulance had not yet arrived. Indeed, it had not in fact yet been dispatched. I checked the Twitter feed of London Ambulance to see if some mass medical emergency had befallen the capital. No. Only a long series of self-congratulatory tweets depicting heroic ambulance service people receiving awards and participating in charity fundraising events.

Do you find it shocking that London no longer appears to have a functional ambulance service? I do. I was born and raised in the City of Westminster. On the (mercifully) few occasions I was ever present at a medical emergency before I left the country in 1993, an ambulance arrived pretty much immediately in response to friends’ childhood fractures, epileptic fits, concussions. On more recent occasions – in Rome last year, for instance, where my son broke his arm – an ambulance came in 18 minutes. A friend with heart pains in Moscow in 2020 had an ambulance with a doctor in at his door within 20 minutes. When I dislocated my shoulder in Istanbul in 2019 help arrived in 15 minutes. But in London? Apparently, it’s two-and-a-half hours.

Rudyard Kipling asked: ‘What do they know of England who only England know?’ I have spent a quarter of a century, almost half my life, abroad. And I know this: Keir Starmer is correct. Britain’s NHS does need to be ‘re-imagined’ as a basically functional health service of the kind that citizens of every developed country (with the single exception of America) enjoy for free.

And the most shocking thing about Daphne’s ordeal? The poor lady’s resignation. The shrug from the two young Samaritans who called her a taxi. Rather than be outraged and ashamed that we are so appallingly served by the NHS, many Brits seem inexplicably proud of it. Have you not noticed that despite spending just as much money as all other Europeans on our national health service, it has ceased to function? Awake, and be angry. Very angry. Your life could depend on it.

Comments