Some years ago there was a study at Harvard that tried to find out what people did when they held an incorrect opinion. Not an opinion of the kind that the era happens to deem incorrect, but one that is actually, provably not the case. The study looked at what happened when that factually incorrect view was introduced to the evidence that it was wrong.

We might hope that the results would be clear: man holding wrong view meets the right view, immediately throws up his hands and asks himself how he could have been such a dolt. Alas, as anyone who has ever been married will know, people do not always concede wrongly held views as swiftly as that. And so the Harvard study showed. When people with an incorrect view were introduced to the correct view, a vast proportion doubled down on their wrong opinion and thenceforth refused to budge.

I am slightly haunted by this study because of how much it says about us human beings. We like to think of ourselves as reasonable, rational types. After all, you rarely meet someone who confesses to being unreasonable and irrational. But we do not really know ourselves, and if reason and rationalism alone drove us then we would be something else entirely. While we are sometimes motivated by reason, we are also fuelled by pride, jealousy and much more.

Changing our mind must count as one of the most curious processes we go through. Indeed, we do not always notice we are going through it. Look at those politicians who seem to become more and more reasonable to you – or the opposite. Is it they who have changed? Or you?

And then there is the question of whether there is any price to pay for changing your mind, or being seen to do so.

Whenever I see Jeremy Corbyn speaking I feel a pang of pity. Although he can be fiery, the poor man always seems tired – not to say exasperated. As well he might be. He has expressed the same few views for 40 or 50 years, and has not changed them one iota. There are some people who admire this, and think that never changing your mind, or your stump speech, is a virtue. But we also know that it can be a sign of other things, including – although not limited to – fanaticism, absolutism and a rather obvious lack of intelligence and curiosity.

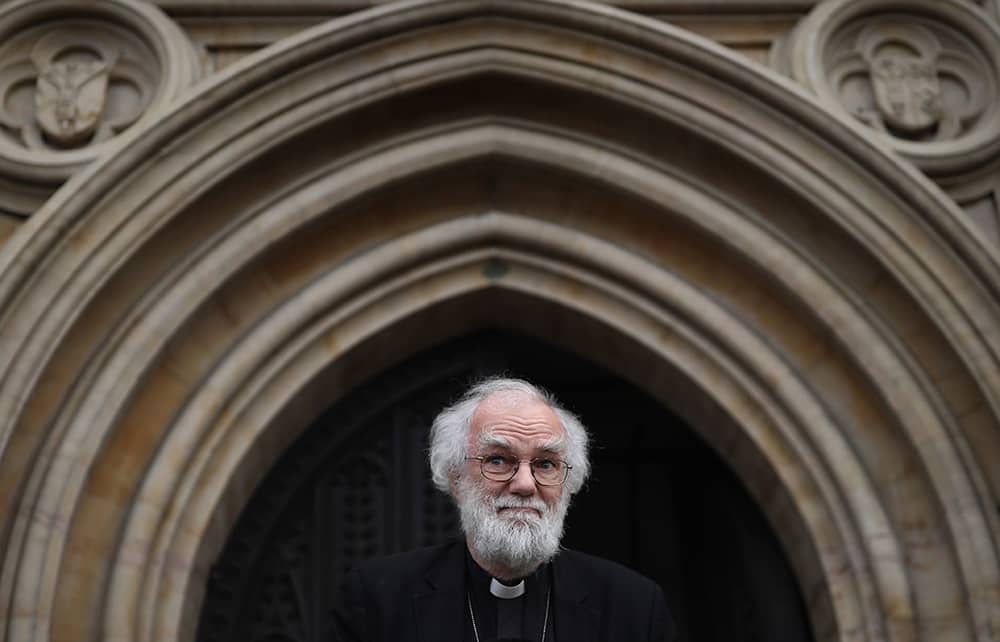

But just as holding on to the same views can bring trouble, so can appearing to change your mind. I was thinking about this recently when trying to parse a statement released by the former Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams.

If rationalism alone drove human beings, we would be something else entirely

Before Williams became Archbish every-one rather admired him. Then he had to try to run the Church of England, and hold the whole thing together, and he seemed to become less and less intelligent with time. I called for his resignation once, and reminded him of this face to face when we found ourselves uncomfortably on the same side of a debate some years later at the Cambridge Union. I semi-apologised to him afterwards at drinks, saying that I really did have to stress to the students what a catastrophic archbishop I thought he had been. ‘Oh no, Douglas,’ he said, with that look of a beaten-up sheep, ‘it was certainly a brilliant tactical move on your part to present both of the other people on your own side as complete dumbos.’

Anyhow, I only ever really disliked him because of his infamous comments backing sharia law for British Muslims. But another thing Williams did while he was Archbishop of Canterbury was to oppose every one of the British government’s proposals on gay unions. He led the church as it opposed civil partnerships and gay marriage. Under Williams, the church did not only oppose the blessing of same-sex unions in churches – as it certainly had the right to do – but also opposed such unions existing in secular law.

As it happens, I don’t hold any of this against him. Williams was simply steering, or being steered by, the views of the Church of England at that time. But it does make his intervention into the trans debate even more confusing. Because last week Williams was one of a group of people to sign a letter to the Prime Minister about the issue of conversion therapy.

As I have described here before, conversion therapy now means two different things. It means what people think it means (trying to persuade gay people that they are not gay) and it also means raising any questions about whether a child with so-called ‘gender dysphoria’ should be medicalised to approximate the appearance of the opposite sex. I am very much in favour of people having the right to question this latter course.

The letter that Williams signed was furiously pro-trans, against ‘conversion therapy’ and absolute in its belief that trans people are obvious, clear and never to be questioned. Indeed Williams appears to have found a whole theology to encompass the new trans goddess of the era. The line that stood out was this one: ‘To be trans is to enter a sacred journey of becoming whole.’

When I read this I was immediately put in mind of Canon Jeffrey John and other gay people whom Williams put through a kind of torture while he was archbishop, all because he could not recognise gay relationships as being in any way on a parallel with straight ones.

Again, I do not hold this view against him. But how can it be wrong for somebody to be in a committed same-sex relationship, whereas having a double mastectomy or a clitorectomy, or having part of a leg or arm flayed in order to have something resembling a penis stitched to the abdomen (sorry about the details), is part of ‘a sacred journey’? I do not know what the answer is. I wonder if Dr Williams knows?

Comments