Despite the economic gloom, ENO’s John Berry is optimistic about the future of opera

Opera director David Alden said in a recent interview, ‘Opera is alive, popular — and hot.’ I agree. Opera is very much in the public eye and thriving in UK opera houses, cinemas and performing arts centres.

However, as we wait to see the outcome of the coalition’s spending review, the arts community has been vocal about its concerns and fears. London is not Munich or Vienna where public subsidy for the arts is a way of life and debated on the same level of necessity as health and education. Yet Britain is revered worldwide for the energy and quality of its performing arts institutions. They make an incalculable contribution to the nation’s spiritual and emotional life — as well as to the economy — and their investment in people and talent is often hugely underestimated.

America is often held up to UK arts organisations as the shining example of the success of private giving with no burden on the taxpayer. But I find this shortsighted. Opera and theatre in the United States are far more conservative because they rely on patronage, whereas with the right balance of private/public money we can take risks (essential if creativity is to flourish). We can experiment and give the public an opportunity to see work they would otherwise not experience. We are in the entertainment business certainly, but the work we do should challenge what opera means today, not only with new commissions but also by continuing to reinterpret and illuminate the thoroughly modern worlds of Shakespeare, Monteverdi and Mozart, for example.

Opening up opera to a new public is important and I feel we have a responsibility to reassess and inject new life into it. Over the past few seasons, English National Opera has done much to attract a new and younger following from the wider arts, and our audience is visibly changing: last season 37,000 people came to one of our contemporary operas, and 30 per cent overall were under 44 years old (an increase from 21 per cent five years ago). And the average age is much lower for the contemporary projects, such as for our recent new immersive opera — The Duchess of Malfi — by Torsten Rasch, directed by Punchdrunk and presented in an abandoned old building in London’s East End, and Philip Glass’s mesmerising Satyagraha directed by Improbable.

We present more new productions each year than any other opera house — and it’s expensive, especially in a climate of cuts. However, the cost can be spread through international co-productions, and this is key to our ability to commission and produce new operas. This season we will generate £3.5 million of overseas investment through co-productions, rentals and commissioning money towards new works for the stage, compared with less than £200,000 ten years ago. We have, for example, joined up with De Nederlandse and will give the UK première of Alexander Raskatov’s A Dog’s Heart, based on Bulgakov’s novel (the book was banned in the USSR until 1987); and we finish the season in June 2011 with the world première of Nico Muhly’s first opera, Two Boys. Thank you, Pierre Audi (De Nederlandse) and Peter Gelb (Metropolitan Opera), without whom neither work would have been possible as both offer substantial financial investment.

We start our 2010/11 season next week with Gounod’s Faust directed by Des McAnuff (the award-winning director of Jersey Boys and Tommy), one of eight international directors to make their UK opera-directing debuts. People criticise us for working with theatre and film directors: they say they are too literal in their approach and are unmusical. I admit not every choice I have made has been successful, but with the talents of our music director Edward Gardner, and the high level of casting, ENO definitely has a palpable buzz.

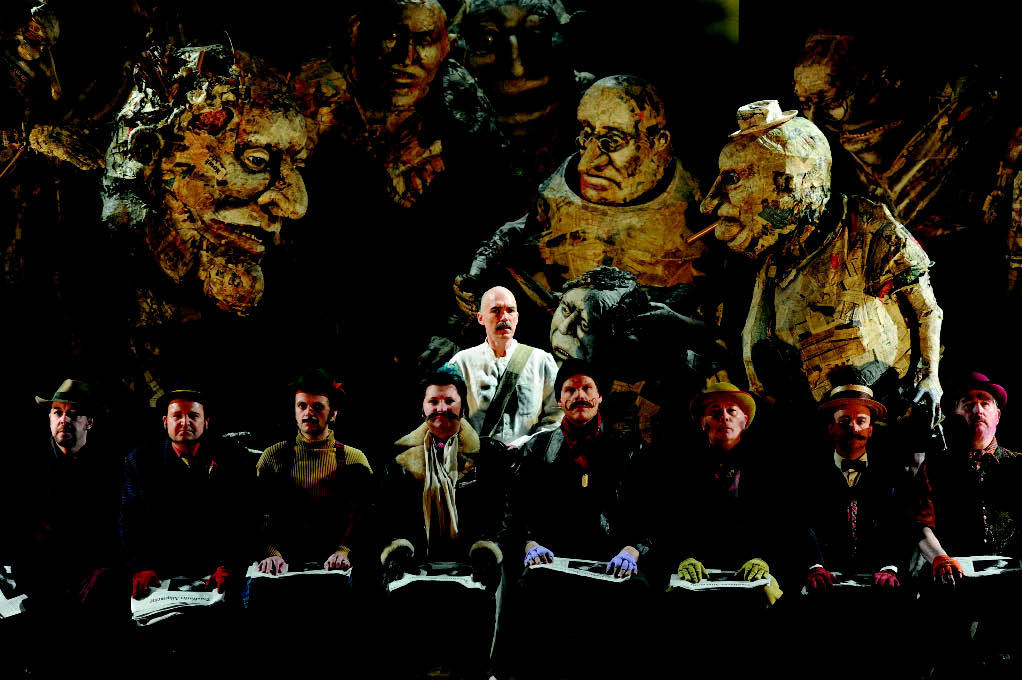

Rufus Norris’s theatre production of Festen at the Almeida left me reeling and his production of Cabaret impressed, so I have asked him to stage Don Giovanni for us. And it was Pierre Audi in Amsterdam who finally encouraged Simon McBurney of Complicite to take on an opera — A Dog’s Heart. He might be new to opera but his work over 20 years or more has integrated text, music, film and physical theatre to create some of the most surprising, adventurous and mind-blowing theatre to be seen in London and across the world. Another newcomer is Terry Gilliam, a brilliant storyteller, and with his cinematic experience and fertile imagination he will make sure there is never a dull moment in Berlioz’s rarely performed The Damnation of Faust. The more I meet Mike Figgis, the more I am aware of how much music is part of his life. He is a gifted composer and performer and will bring all of his multimedia magic and visual flair to Donizetti’s Lucrezia Borgia.

We continue to work with two of the best international opera directors: the brothers David and Christopher Alden, both of whom have produced for ENO some of the most compelling opera seen anywhere over the past four years. They will create two new productions: Radamisto and A Midsummer Night’s Dream. The great European venues continue to be a source of inspiration: I’ve seen wonderful work at Berlin’s Schaubühne Theatre, for example, led by Thomas Ostermeier, and it is one of Ostermeier’s protégés, the young Australian Benedict Andrews, who will create a new production of Monteverdi’s The Return of Ulysses for us and the Young Vic theatre next year. And we have successfully courted the young Russian opera director Dmitri Tcherniakov (whose Eugene Onegin was seen in London recently), who makes his ENO debut with Verdi’s searing Simon Boccanegra.

Staging familiar and new work in ways that make them resonate for contemporary audiences is essential for the future of opera. I hope that in a climate of uncertainty, ENO’s 2010/11 season will fly the flag for creativity and quality, and go some way to proving opera in the UK is worth the investment.

John Berry is artistic director of English National Opera.

Comments