Until about six months ago, it would have been hard to find a more inoffensive politician than the Labour backbencher Kim Leadbeater. A well-liked, upbeat, down-to-earth Yorkshirewoman, she entered politics because of a personal tragedy, the murder of her sister, the MP Jo Cox, in 2016. When asked on a Spectator podcast what was the worst piece of advice she had ever received, Leadbeater half-joked: ‘Have you thought about being an MP?’ Visibly a normal, friendly person plunked down in SW1, she won many admirers and attracted little controversy.

Then in September Leadbeater came top of the private members’ ballot and chose to take up the cause of assisted suicide. The current law, she argued, is cruel to those dying in terrible pain. With the Prime Minister quietly supportive, and celebrities such as Esther Rantzen vocally backing her, it seemed the perfect moment.

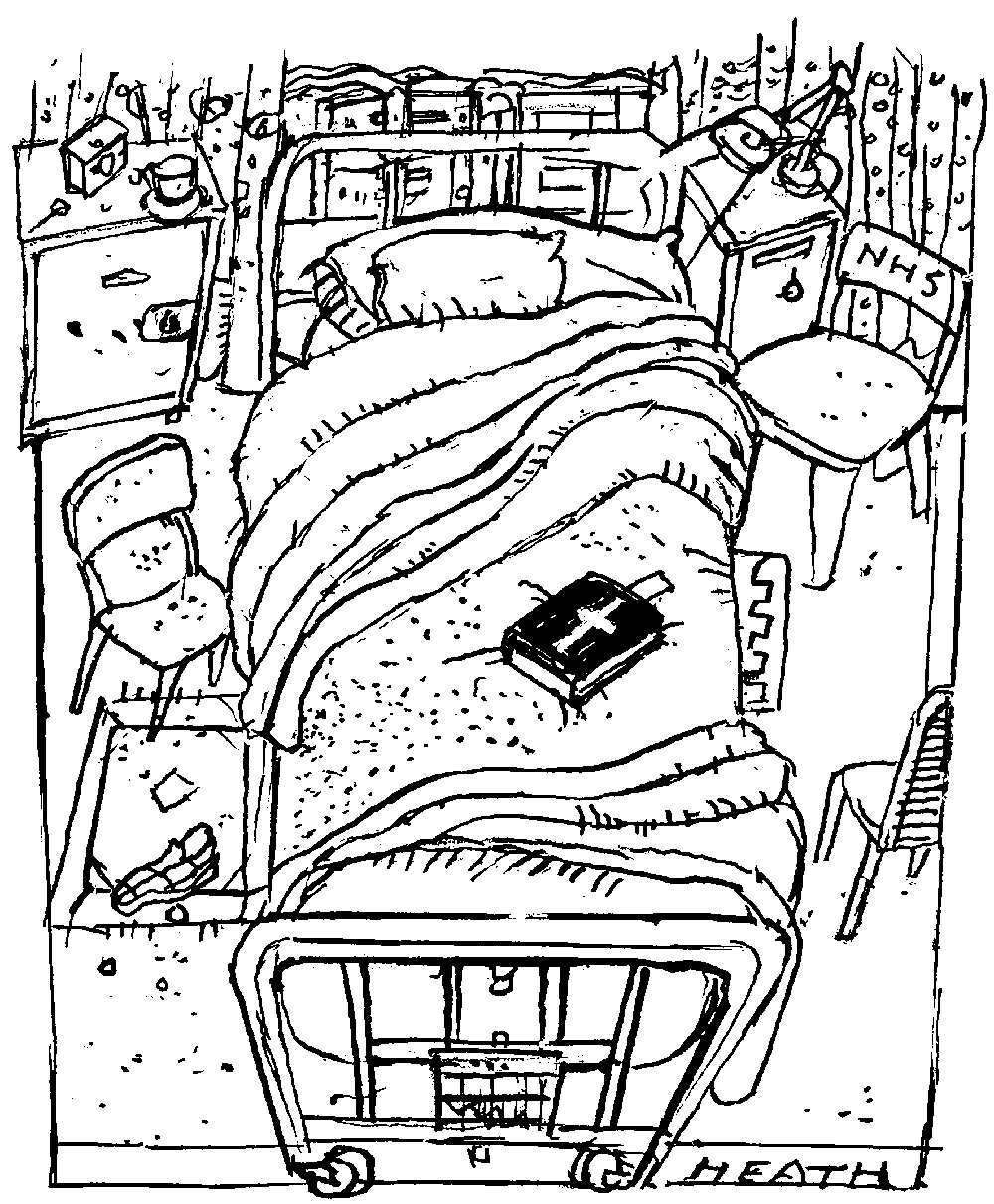

So how did we end up here? Six months after Leadbeater launched the Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill, a group of Labour MPs have pronounced it ‘irredeemably flawed and not fit to become law’. It’s ‘becoming beyond a joke’, according to the Tory MP John Lamont. Leadbeater’s bill has been hectically rushed, then frantically delayed, and somewhere along the way has lost its biggest safeguard, the inclusion of a High Court judge. The seasoned policy expert Richard Garside, director of the Centre for Crime and Justice Studies, says he has ‘never seen a bill less up to scratch’. For some, the imbroglio threatens to overshadow the government’s own reforms. ‘It’s become an embarrassment,’ says one Labour MP. ‘It’s more than a mess. A mess is something you can fix.’

From the start, the bill has faced major questions. Wes Streeting, the Health Secretary, warned that people might ‘choose’ assisted suicide because they felt like a burden on their loved ones, or because proper palliative care was unavailable. Shabana Mahmood, the Justice Secretary, also opposed this ‘profound shift’ towards a ‘duty to die’.

Even the bill’s most basic aspects do not hold up to scrutiny. Applicants need a six-month terminal prognosis, but such predictions are notoriously unreliable: a fifth of those given six months to live are still around three years later. The bill forbids ‘coercion’ – but in a world where only 5 per cent of recorded domestic abuse crimes result in a conviction, how many vulnerable people will slip through the cracks?

‘Assisted suicide is being sold to people as a way to avoid pain,’ says Baroness Finlay, former president of the British Medical Association. ‘But the bill doesn’t mention pain, and an amendment to make it the only qualifying reason was rejected. Pain was very poorly understood 30 years ago – often people didn’t know how to prescribe morphine and the use of nerve blocks was rare. Today we know what to do: the real problem is the lack of specialist services. But the evidence from abroad is that assisted suicide slows palliative care advances, to fund ending lives.’ European countries which forbid assisted suicide, for instance, have increased palliative care provision three times more than those that permit it.

Other alarm bells started ringing. The leading criminologist Jane Monckton-Smith said the bill could be ‘the worst thing, potentially, that we have ever done to domestic abuse victims’. The civil liberties group Liberty warned that it had all the makings of bad law. The head of the national suicide prevention strategy, Sir Louis Appleby, said it undermined the basis of his work.

At the bill’s second reading on 29 November, Leadbeater offered a deal: vote for it now and it will be scrutinised to the nth degree in committee. Expert witnesses would be called, amendments considered, every line of the bill examined, she promised wavering MPs – then you can properly make up your minds at third reading.

MPs took the deal, by 330 votes to 275. But nothing since has gone according to plan. ‘People are less enamoured of Kim now,’ says a Labour colleague. ‘After the last few years in politics, MPs want any process to be beyond reproach. They couldn’t have imagined what was going to happen in the bill committee.’

‘It’s become an embarrassment. It’s more than a mess. A mess is something you can fix’

First Leadbeater gave herself a two-thirds majority on the committee (the Commons margin had been 55/45). Then she picked a witness list skewed 80/20 towards the bill’s supporters, omitting Disability Rights UK (which opposes the bill) and blocking the Royal College of Psychiatrists (neutral but with some penetrating criticisms). After an online outcry, both were hastily included.

Among the expert witnesses was Professor Allan House, an NHS psychiatrist specialising in the psychology of severe illness. He was taken aback, he says, to find himself listening to ‘pre-prepared’ speeches from the bill’s supporters ‘to say that the bill was so fantastically safe’. There was no ‘serious attempt to understand the issues and what the pros and cons of the bill were’. As for Leadbeater and her most voluble supporter, the Tory Kit Malthouse: ‘I don’t quite know how to put it politely, but they strike me as way out of their depth.’

It’s hard to summarise the committee’s proceedings, except with a kind of Homeric catalogue of rejected amendments. MPs proposed changes to bar doctors from raising assisted suicide unprompted; to prevent people receiving lethal drugs because they feel like a burden; to explicitly rule out ‘encouraging’ someone to apply; to narrow the definition of terminal illness to exclude conditions such as diabetes or anorexia; to raise the standard of proof of eligibility from ‘balance of probabilities’ to ‘beyond reasonable doubt’; to allow families to appeal if they think an assisted suicide has been wrongly approved. All these proposals were voted down.

There were amendments to guarantee a palliative care consultation for every applicant; to ensure a meeting with a mental health professional at the start of the process; to require doctors to check for ‘remediable suicide risk factors’ such as depression; to make it impossible to apply straight after a terminal diagnosis, when people are most vulnerable to suicidal feelings; to ensure that doctors ask why someone wants an assisted suicide; to require that the lethal drugs – which according to some researchers could put patients at risk of highly distressing deaths – are approved by the official regulator, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. These were voted down as well.

All this was accompanied by a series of disconcerting public statements. Leadbeater declared that families discouraging loved ones from assisted suicide were guilty of ‘coercion’, and that doctors should be allowed to raise the subject even with under-18s (who are ineligible). Malthouse asserted that the terminally ill can’t be classed as suicidal: ‘To me, suicide is a healthy person taking their life.’

In this context, sceptics have grown frustrated with the relentless everything-is-awesome breeziness of the bill’s supporters. ‘There is an element of the Ministry of Truth,’ says one Labour MP. Another summarises Leadbeater’s line as: ‘These are the strongest safeguards in the world, and we’re making them even stronger, and we’re dropping the judge.’

The bill’s supporters had made a great deal of the provision that every case had to be approved by a High Court judge. But the Ministry of Justice said that would overburden the courts; so the judge has been replaced with an ‘expert panel’ of a psychiatrist, social worker and KC, distantly and sympathetically overseen by a new quango, the Voluntary Assisted Dying Commission. The commissioner – inevitably dubbed the ‘death tsar’ – will be a retired or current judge, but in either case will have no judicial function and little direct involvement with the panel’s decisions. Instead, they will be tasked with monitoring their own commission.

‘If we haven’t fixed your GP surgery but have allowed your nan an assisted death, what does that say?’

The new panels can’t summon witnesses: if they suspect a woman is being coerced and invite her husband to answer questions, he can just put the letter in the bin. The panel has to ‘hear from’ an assessing doctor, but there’s no obligation to ask anyone any questions, and the whole thing can be done over Zoom. Even the applicant themselves may not have to be heard from, if there are undefined ‘exceptional circumstances’. Leadbeater attempted to rebrand this process as ‘Judge Plus’, which did not exactly dispel the sense that there is too little scrutiny going on and too much PR.

Speaking of PR, it’s hard not to wonder about the influence of the campaign group Dignity in Dying, which spends more than £2 million a year, a third of it on campaigning. It is clearly helping Leadbeater, who gave one interview sitting next to a large Dignity in Dying placard, but did it also shape the bill? All the group will say is that it ‘shares… policy expertise with parliamentarians across the House’. It’s hard to be sure who is actually driving the train. Or, for that matter, of the train’s ultimate destination. Dignity in Dying declined to comment when I asked if it would campaign in future for any further change in the law.

Another great unknown is the future of the NHS. The bill features a startling clause which redefines NHS legislation, so that its duty to ‘improve health’ can include assisted suicide. The government has said that private firms can be involved, raising the disquieting prospect of an outsourced, for-profit suicide service.

Care homes and hospices would also find themselves on the front line. Some, no doubt, would close down rather than offer lethal drugs to their clients: there were amendments to give them legal protection from being forced to provide it, but Leadbeater and Malthouse squashed those proposals too.

Officials at the Department of Health face a logistical nightmare in working out the practicalities. Hence the recent extension of the implementation period, which in turn nudges the bill towards the awkward date of 2029. ‘The prospect of Keir [Starmer] having to appoint a death tsar in the run-up to the next general election is pretty concerning,’ says a Labour source. ‘If we haven’t fixed your GP surgery or your hospital, but we have allowed your nan to have an assisted death, what does that say?’

The bill will fail if 28 MPs change from aye to no. Two – Reform’s Lee Anderson and his ex-colleague Rupert Lowe – have already switched, and others have let it be known they’re considering it. But nobody on the Labour benches wants to take the spotlight by going public. Even privately, few are eager to discuss this terrifyingly large decision. ‘There’s a sense of dread,’ says one member of the 2024 Labour intake. ‘For or against, you have a knot in your stomach.’

The third reading vote, which will be held probably next month or in June, is not exactly the last word – the Lords are an unknown quantity – but it is likely to be decisive. On one side, the hope that our institutions, and the state itself, can be reshaped around the ideals of choice and autonomy. On the other, the belief in a fundamental, blanket protection for the vulnerable. No vote in our lifetimes, perhaps, will tell us so much about what kind of country we live in.

Dan joined the latest Edition podcast to discuss Assisted Dying, alongside the Revd Fergus Butler-Gallie:

Comments