As one might expect from a 103-year-old organisation, the BBC has a very high opinion of itself. Outside Broadcasting House stands a statue of George Orwell. Inscribed next to it is a quotation by him: ‘If liberty means anything at all, it means the right to tell people what they do not want to hear.’ A noble sentiment, and a more flattering testament to the corporation than Orwell’s description of it after working there during the second world war: ‘Something halfway between a girl’s school and a lunatic asylum.’

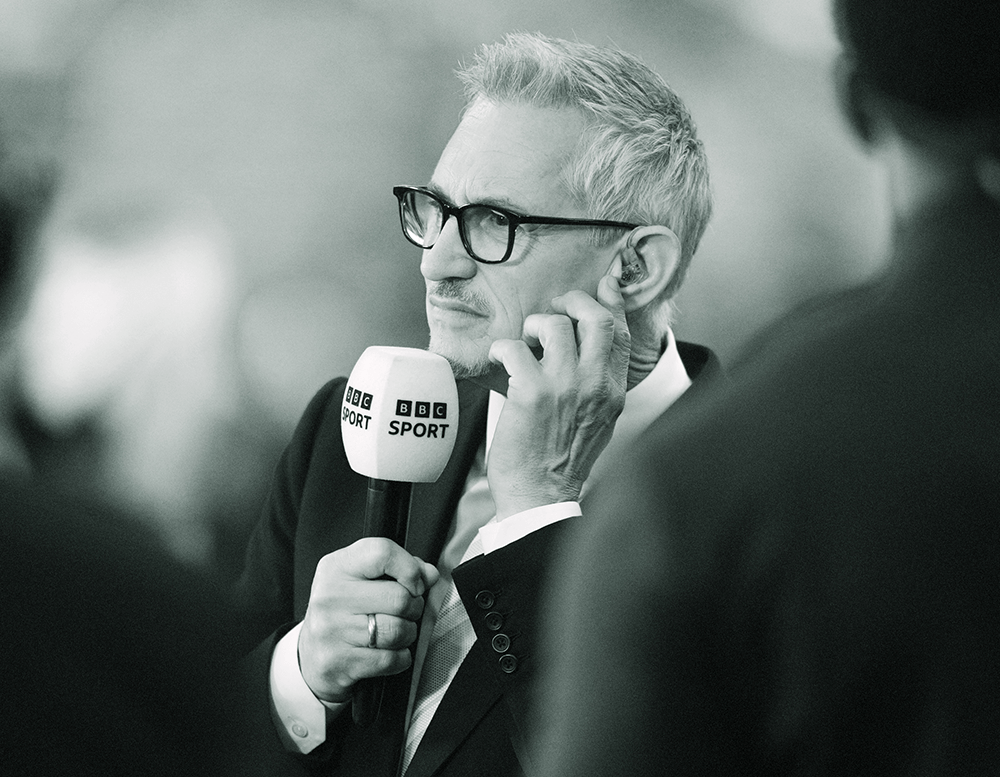

In his growing outspokenness, the football pundit Gary Lineker might have thought that he was channelling Orwell. Even before he was accused of sharing anti-Semitic emojis on Instagram, his handsome salary and his unwillingness to trim his social media output to fit his employer’s impartiality rules were making his role as Match of the Day presenter untenable. Yet the Lineker of today curiously embodies Auntie better than anyone else: smug, expensive, out of touch.

Our national broadcaster resembles the monasteries of Tudor England on the eve of their dissolution. Once a focal point for enlightenment, the BBC now houses a privileged and costly class that has forgotten its duty to the public. Mired in scandal, financially unviable and marooned in a changing world, the corporation is ripe for reformation.

The BBC was created in 1922 in response to the proliferation of radio. In the United States this had led to the swift creation of hundreds of stations. Frightened by this audio anarchy, Britain’s six leading radio firms established a single, state-approved broadcaster. Under John Reith’s direction, the BBC aimed to make available ‘the best that has been thought and known in the world current everywhere’ to the masses.

In the ensuing decades, Reith’s commitment to inform, educate and entertain triumphed. In the second world war, the BBC gave hope to the people of occupied Europe. In the postwar years, the Beeb became central to national life, bringing events such as the coronation to millions or uniting the public around a common national culture of the six o’clock news, Morecambe and Wise and Test Match Special – as much a cornerstone of postwar Britain as the NHS.

In YouGov’s ranking, the BBC sits at spot 218, sandwiched between Braun and Nutella chocolate spread

The same cannot be said today. In YouGov’s ranking of brands by favourability, the BBC sits at spot 218, sandwiched between the grooming product purveyor Braun and Nutella chocolate spread. It hasn’t had the easiest few years. The plaudits for its coverage of the Queen’s funeral evaporated after Huw Edwards’s disgrace and questions over what the corporation knew about his arrest and when. Lineker’s denunciations of Israel followed the scandal surrounding the broadcast of Gaza: How To Survive a Warzone, a documentary narrated by the son of a Hamas official. The BBC has arranged an independent investigation of its Arabic channel following allegations of anti-Semitism.

The corporation faces challenges far more existential than the controversies generated by any one presenter, programme or channel. It is trapped between the Scylla of a changing media landscape and the Charybdis of its own disconnection from the country it is supposed to address.

When the licence fee was first introduced, it was a genuine subscription, paid to access all that was broadcast. Yet since ITV’s launch in 1955, the fee has become a proscription required by anyone wishing to watch television, an absurdity that accelerated as channels proliferated. Now that streaming services have shattered the traditional broadcasting model, the fee has become unsustainable. The millions who have grown up watching Netflix on their phones are unlikely ever to pay a £175-a-year television tithe. In 2022, only one in 20 of those aged 18 to 30 watched the BBC live each day; a third never watched at all. Each year, the number cancelling their licence only grows – more than half a million in 2024 alone.

Even then, do those who do still cough up receive value for their money? As per Orwell’s Animal Farm, viewers will look between the BBC and its commercial rivals and find it impossible to say which is which. Claudia Winkleman’s ubiquity speaks of a corporation that has abandoned its cultural mission for the shameless pursuit of ratings. What would Reith – the son of a Presbyterian minister – have made of I Kissed a Boy or Alan Carr’s Picture Slam?

It is in its news output that the BBC’s struggles are most obvious. However fervently the corporation’s higher-ups proclaim their impartiality, Lineker’s posturing was indicative of the broadcaster’s progressive and metropolitan tilt. An institution staffed by arts graduates in London and Manchester struggles to understand the swathes of the country that do not share its liberal instincts. On the Brexit debate, on ‘grooming gangs’ and immigration, the corporation has proven itself to be disengaged from the many on the issues that concern the British people the most.

The debate over the BBC’s future will become more pressing as the licence fee’s 2027 renewal approaches. The challenge is to find a funding model that guarantees the corporation’s sustainability while encouraging the BBC to take greater notice of the Britain it has ignored. And if the BBC cannot fix itself, there are plenty of would-be Thomas Cromwells itching to dissolve it.

Comments