I sometimes think the classical record industry would collapse if it weren’t for the Goldberg Variations. Every month brings more recordings of Bach’s monumental, compact and rhapsodic keyboard masterpiece. And that’s impressive, given that nowhere else does the composer demand such sustained technical brilliance from the performer, who must execute dizzying scales and trills that wouldn’t sound out of place in one of Liszt’s fantasies.

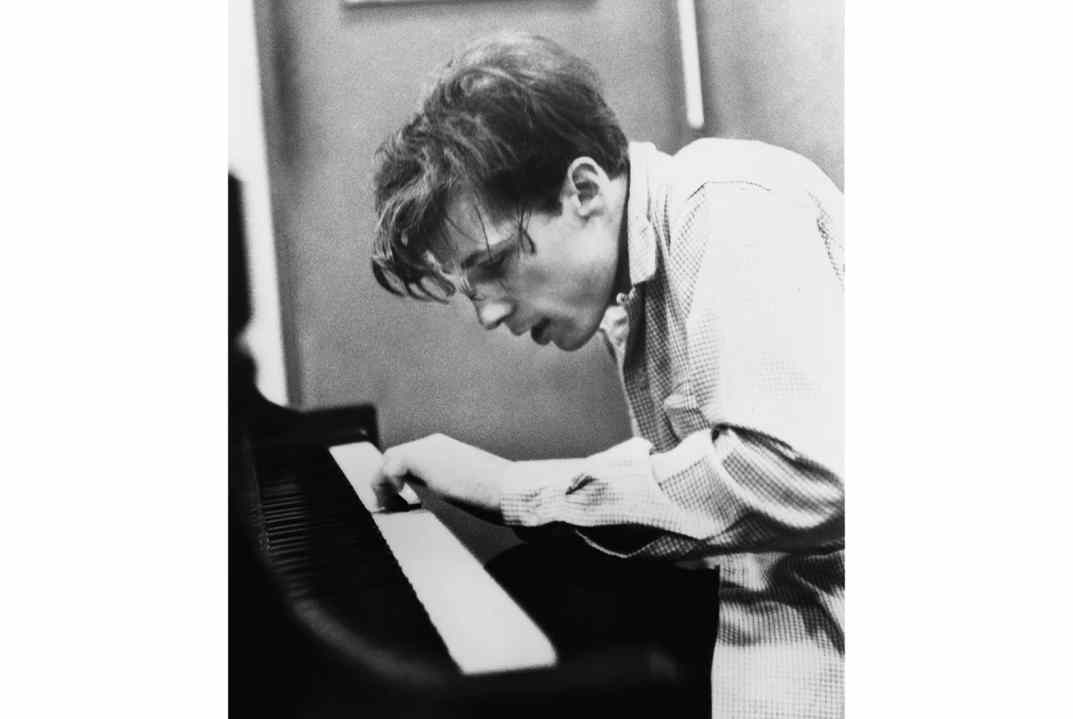

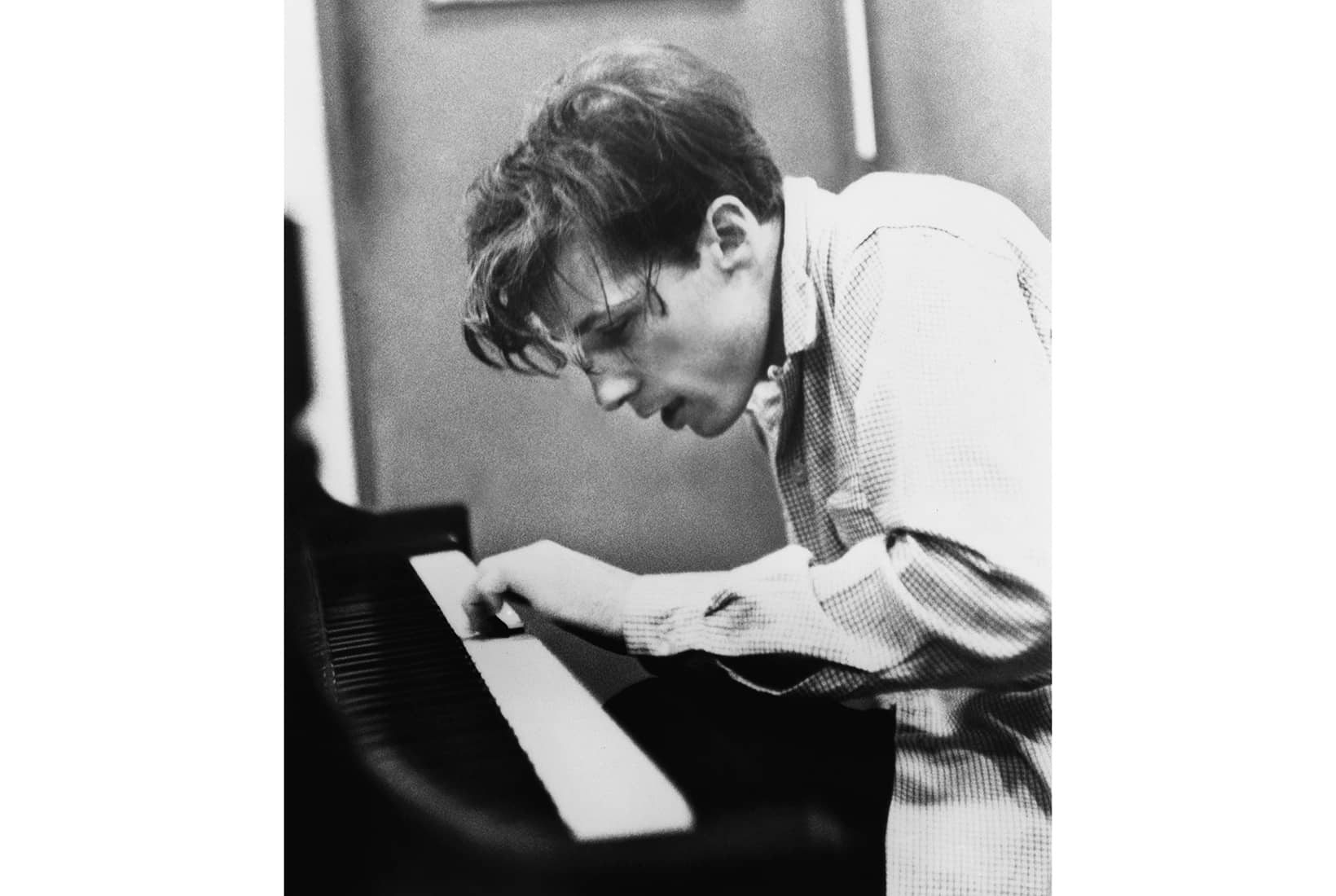

If the Goldberg Variations are an ordeal for harpsichordists, they’re a bloody nightmare for pianists, because they have to tackle music written for two manuals on just one. Their fingers tumble perilously over each other; it looks a bit like high-speed knitting. When the 22-year-old Canadian prodigy Glenn Gould — already dosed up on the barbiturates that would shorten his life —shuffled into Columbia’s studios to record the Goldbergs in 1955, there wasn’t a single piano performance in the catalogue. (Claudio Arrau’s 1942 recording didn’t see the light of day for decades.) I imagine big-name pianists thumbing through the 30 variations and thinking: ‘Nah. Too much work for too little reward’ — and then wincing when Gould’s Goldbergs became the bestselling piano record of all time.

Nowhere else does Bach demand such sustained technical brilliance from the performer

Now we have access to about 300 recordings, and the number is growing all the time. This year, three Goldbergs were released on the same day, 27 August. Quite a few of these are self-financed, so we can’t assume there’s unlimited public appetite for new Goldberg Variations. But tickets to live performances — still comparatively rare, thanks to the risk of finger-collision — usually sell out quickly.

There’s only one musical experience comparable to it: Beethoven’s Diabelli Variations. Posterity has never decided which work is greater, but there’s a consensus that no standalone set of variations written after Beethoven — solo, chamber or orchestral — approaches them in stature. (The pianist Igor Levit believes Frederic Rzewski’s gimmicky The People United Will Never Be Defeated! is the third person in a Holy Trinity of variations, but I doubt he’d think that if Rzewski hadn’t shared his toxic left-wing views.)

In the public affections, however, Goldberg beats Diabelli. If Gould had chosen to record Beethoven’s kaleidoscopic epic, with its long stretches of mid-flight turbulence, he’d never have sold two million copies. Bach’s writing is far less abrasive. On the other hand, until 1955 no one guessed that listeners could be so utterly seduced by between 40 and 90 minutes (depending on tempo and repeats) of music almost entirely in G major, including some of the most rigorous exercises in counterpoint ever attempted.

Every third variation is a canon, sometimes inverted, and the interval between the two voices steadily increases. Also, these aren’t variations on a tune. The graceful melody of the opening Aria returns unchanged at the end but in the meantime disappears. That’s because these are variations on the ground bass, not the tune. They are one of Bach’s supreme achievements as a structural engineer.

Put like that, the Goldberg Variations sound about as enticing as post-Webern dodecaphony. But a lovely paradox of Bach’s music is that its most intricate musical logic often inspires its most daring leaps of imagination. The inversion of figures, the integration of ground bass and canonic line, the cunning experiments in symmetry — well, it’s nice to know about these things, but don’t let that distract you from the terrific and perhaps sadistic fun Bach is having making the performer’s hands chase each other.

The Goldbergs must convey this sense of virtuosic fun. I’m not the best judge of which harpsichordists achieve that, since listening to the harpsichord isn’t my idea of fun. But I make an exception for Pierre Hantaï, who scampers like a schoolboy through the knottiest thickets of semiquavers. My favourite recent piano recordings is by the artist known simply as Ji, who supplements Bach’s inventions with a few naughty ones of his own: for a few seconds in Variation 28, it’s as if Earl Hines has pushed him off the piano stool. In contrast, all those transcriptions for string trio or baroque orchestra fall at the same hurdle. They can’t, by definition, reproduce keyboard flourishes. It’s like Daleks not being able to climb stairs. Accordionists, on the other hand, can pull it off, and the mysterious resources of their two-manual instruments have given us some thrilling Goldbergs (and Scarlatti Sonatas).

In the end, though, the search for the gold standard will always take us back 66 years to a converted Presbyterian church on East 30th Street, Manhattan, and you-know-who slouched on a chair just 14 inches off the floor. Columbia’s technicians could hardly believe their eyes. But nor could they believe their ears when, to quote Otto Friedrich, ‘he made Bach’s creation leap and plunge and fly’. Hundreds of recordings later, no one else has worked such a miracle, and that is why Glenn Gould still owns the Goldberg Variations.

Comments