War – huh – what is it good for? According to Duncan Weldon, throughout most of history it’s been fantastic for economic growth and development and has perhaps fuelled technological innovation and more.

Blood and Treasure is a delightfully quirky approach to military history. Colonial Spain was thought to be cursed by the gold brought home from its colonies in the New World, since the crown somehow bankrupted itself multiple times during this period, despite the riches. Weldon contends that since the gold meant that Spain’s monarchs did not need to approach parliament for money, it left them untethered from their economies and constraints.

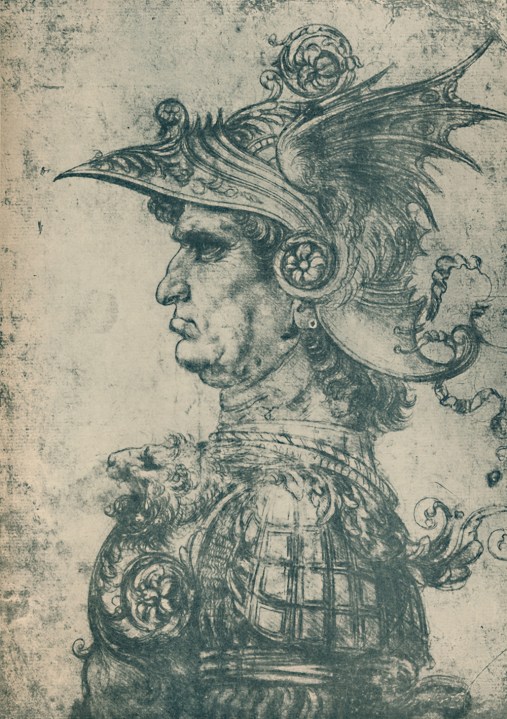

He also offers an alternative theory for why the Renaissance originated in Italy, suggesting that it was a result of the particular way in which Italian city states waged almost perpetual war on each other by means of mercenaries. Commanders of such companies would infinitely prefer to drag out a conflict and avoid major battles – in which they might die. Huge fortunes were thus amassed, which translated into social status through patronage of the arts.

Given that the book covers a vast period and range of geographies, it is perhaps best viewed as a collection of vignettes, each containing a lesson about how combat interacted with the everyday economy. The most convincing example of the destructive, coercive force of war being also a major driver of growth and better living conditions can be seen in a study of India. Weldon describes how researchers pinpointed the dates and locations of conflict in the subcontinent going back 1,000 years. They then used satellite imagery from 1992 to 2010 to assess the level of night-time electric lighting across the country (creating proximate measures for economic development where no such granular data existed) to check for a correlation. They found that areas where there had been intensive fighting tended to be more economically developed, even centuries later. The conclusion was that warfare leads to a strengthening of local governments and institutions, which in turn is conducive to growth.

When the book turns to more recent times, such intriguing, counterintuitive stories disappear. Pre-industrial societies, Weldon explains, worked below their capacity, so when extra materials were needed for warfare it resulted in growth. Post-industrial societies do not have spare capacity waiting to be used, so modern warfare, in its destructiveness, ends up killing growth.

In a sense it is convenient that the story changes, given the difficulties that might result from claiming any modern conflict would actually be a good thing when the casualties are those who might otherwise be alive today. But it inevitably means that the book’s later pages are less lively.

Blood and Treasure risked falling between two stools – being military history targeted at people who don’t normally read it, satisfying neither warfare nerds nor those looking for a post-Freakonomics hit. Thanks to an obvious deep love of the subject, a deft choice of examples and some thoroughly satisfying human stories, Weldon has at least made warfare a good thing to read about.

Comments