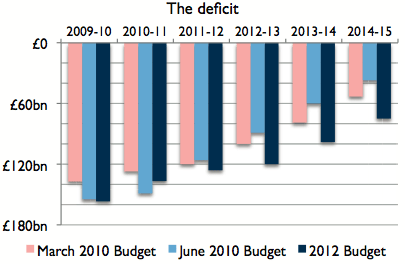

Will George Osborne’s refusal to look again at high levels of state spending become the greatest risk to Britain’s economic stability? There have been plenty of rude comments about the Chancellor’s supposed tactical ineptitude in the weekend press, but he has still managed to keep on borrowing and have almost no one notice. Osborne’s iron commitment is to spending, and a programme of cuts which total just under 1 per cent a year. His commitment to deficit reduction is flexible, as his three Budgets have demonstrated:

Osborne spent the election campaign berating Labour for its lack of ambition in halving the deficit in four years. He’s now doing it in five, but no one points this out. Quite a result. And, yes, Gordon Brown may also have done the same in the face of the slowdown — but Brown would have been lambasted by the opposition for breaking his promise. Osborne has not just got away with it, but is being congratulated for sticking to a plan he abandoned long ago. He has brilliantly outmaneuvered Ed Balls, whose ridiculous ‘harsh, deep cuts’ attack line has rendered him mute on real story: that Osborne’s proposed savings are not ambitious enough, and may yet cost Britain its AAA rating.

I’ll leave CoffeeHousers with this graph from Citi. It shows Britain’s projected debt increase, and compares it to that of countries with AAA rating. It suggests that there may be trouble ahead.

Right now, Osborne can borrow so cheaply because of QE: he has the Bank of England buying up a quarter of all government debt with freshly-minted cash from Sir Mervyn’s Magic Money Machine.

But this can’t last forever. I argue in my Telegraph column that another spending review is needed. Osborne said in the Budget speech that his first commitment is to ‘stability’.

The high spending he inherited may soon become the no.1 threat to that stability.

A P.S. for the small print: In office, Osborne has used a specific (narrower) definition of the deficit: the cyclically-adjusted deficit which his 2010 Budget showed would be eliminated in

the financial year 2014-15. His decision to borrow more, in response to the slowdown, has added another two years to the timetable. So a cyclical surplus is now expected in 2016-17. See Table C1

here, and Table 1.2 here, for comparison. There are, as yet, no plans for elimination of the unadjusted deficit.

Comments