The first Cold War thriller I ever read – before MacLean, before Le Carre, before Clancy – was Biggles Buries a Hatchet, from 1958, in which James Bigglesworth MC, DSO, of the Air Police, heads for Siberia to spring his nemesis Von Stalhein from a Soviet prison camp. The wily old German had first crossed swords with our hero in aerial combat over the Western Front, later thrown his lot in with the Nazis, and then deftly switched sides to serve the Communist Bloc after the second world war, but had run out of luck and been sent to the gulag after a falling out with his new masters. I must have been about ten or 11, and was just beginning to get a handle on what had been at stake in the great ideological struggle of the late twentieth century (which had then only recently concluded).

The series puts forward a well-developed and admirable moral code which is very easy to sneer at and mock, and rather more difficult to surpass

Biggles himself was rather older, of course. Given that he was a decorated veteran of the first world war, he was at least 60-odd by the time he so magnanimously rescued his old foe from the dastardly Reds in the late fifties, with 30 instalments in the series still to come.

Given his vintage – he grew up in India during the heyday of the British Raj, as we learn in The Boy Biggles – it is perhaps inevitable that Biggles has come under fire from various contemporary critics who expect us to be shocked that a British military hero from a century ago held views that might not pass muster in a university common room or a Guardian editorial conference in 2025.

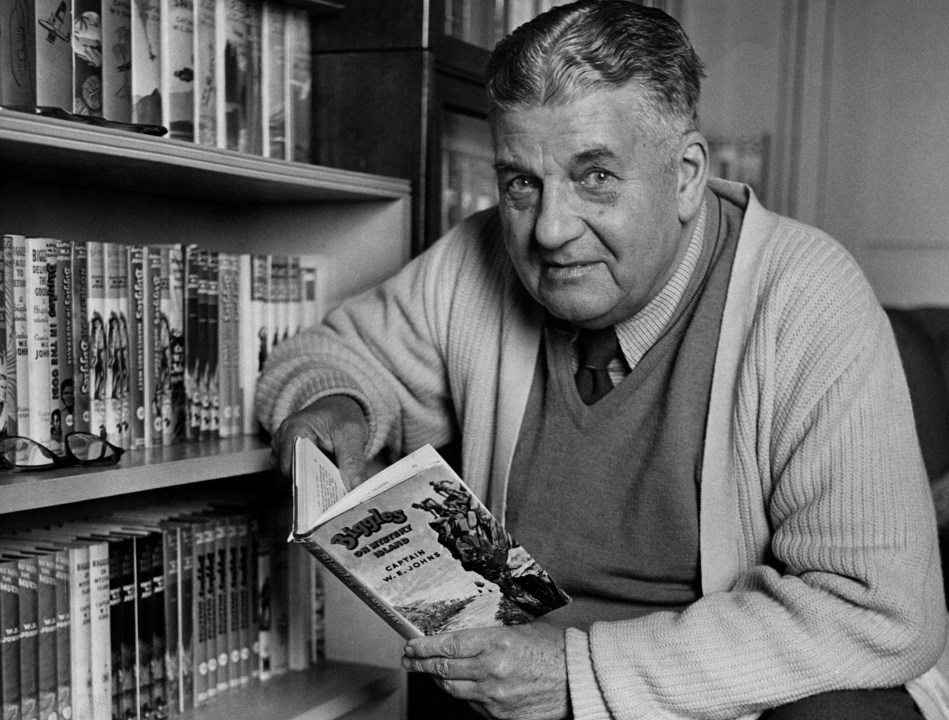

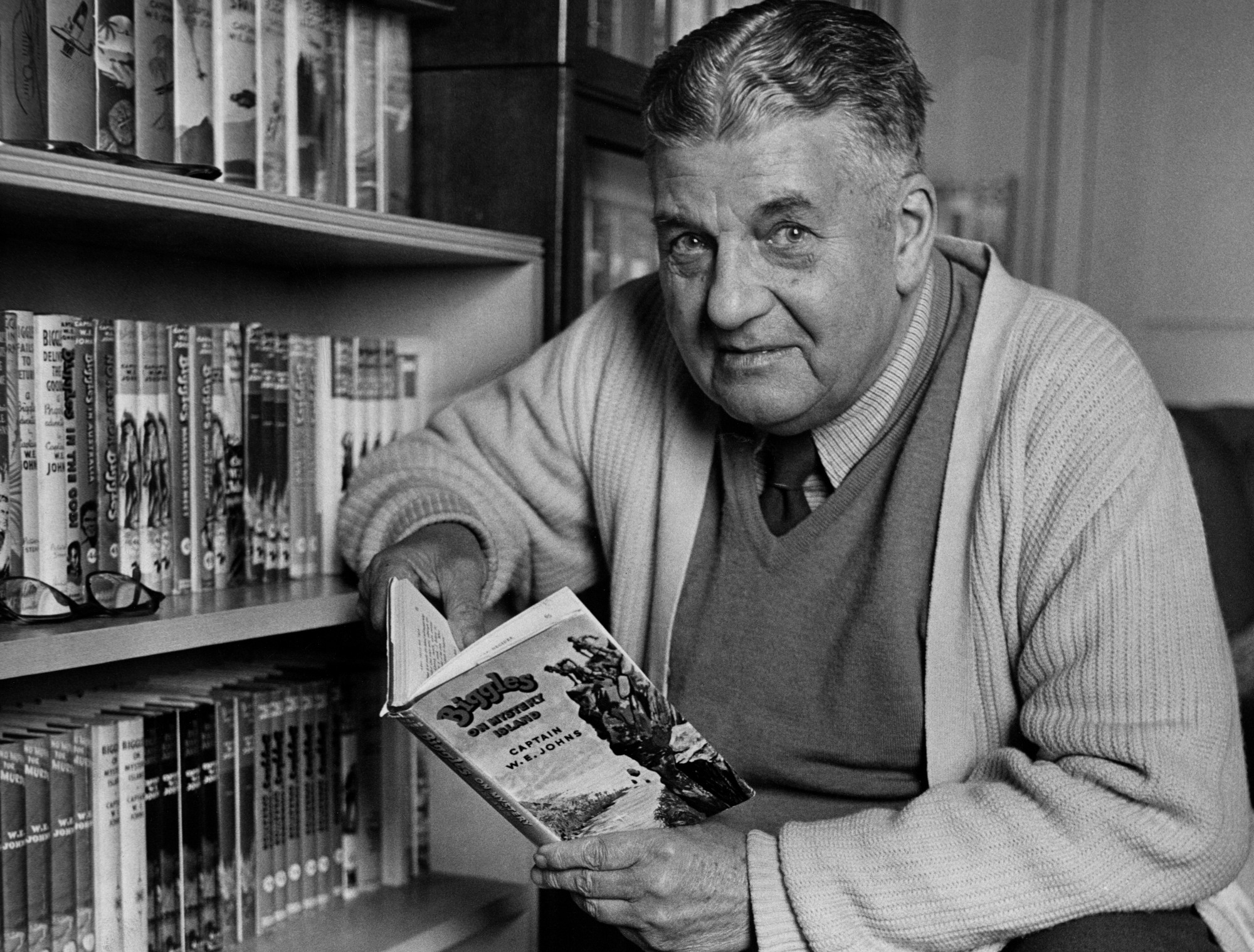

A recent addition to the ranks of such critics was Tom Tugendhat MP, who noted in an interview that many of the Biggles books had been added to the Forbidden Section of the Tugendhat family library, and would not be read to his son at bedtime. He suggested that ‘W.E. Johns’ views on people are more objectionable’, presumably a reference to the imperialist views espoused in the books.

Fair enough, it’s a free country. All the same, there is a good deal to be said in defence of the Biggles oeuvre – which was, incidentally, enormously successful all over the world, suggesting that the alleged British jingoism is not so very unbearable to those unfortunate enough to be born Abroad.

To be sure, the Biggles books are not great literature, and it’s advisable to not think too hard about the chronology; Captain W. E. Johns certainly didn’t. Only three years and half a dozen books into the series, the original presentation of Biggles as a 17-year-old rookie pilot who only gets into action in 1916-18, as seen in The Camels are Coming and Biggles Learns to Fly, is quietly superseded by a more experienced and poised tough guy, ready to be dispatched on a dangerous spy mission behind enemy lines in Palestine (Biggles Flies East). Similarly, Biggles and pals – Algy, Bertie, and Ginger – barely seem to age between their heroics in the skies of Flanders and the Battle of Britain.

But if we take a deeper look, the series, as with many of the now unfashionable Boy’s Own adventure yarns, puts forward a well-developed and admirable moral code which is very easy to sneer at and mock, and rather more difficult to surpass. Reading the books as a boy, I learned that you should be loyal to your friends, that you should love your country and fight for what is right, protect the weak from the cruel, and extend mercy to defeated enemies. It would be fascinating to know, specifically, what sophisticated moderns find objectionable about such axioms. At one point in Biggles Flies East, which I recently read to my own children, Biggles objects to the idea of blowing up a German-controlled dam because it would doom thousands of German troops stationed in the desert to an agonising death from thirst. In the same book he risks his own life to save a crashed German pilot, showing a chivalrous magnanimity which is presented as the obviously correct and honourable course of action.

And what of the supposed advocacy for European racial supremacy? In some of the novels and stories, Biggles does express strongly paternalist views about the civilising mission of Empire. On the other hand, such views were common at the time, and are not inherently sinister. He is also an admirer of India, and speaks fluent Hindi. W. E. Johns, for his part, was no crypto-fascist: he expressed early opposition to appeasement of Nazism, and appears to have favoured British intervention on the Republican side of the Spanish Civil War. His overall political stance seems to have been a strong and unwavering belief in the superiority of the British civilisation of ordered liberty, and hostility to its foes.

In this respect, he resembles another much-criticised but enduringly popular writer of patriotic thrillers, John Buchan, whose main hero Richard Hannay embodies and espouses the same kind of earnest, straightforward British fair play. Here were men who could read Henry Newbolt’s Vitai Lampada – ‘Play up! Play up! and play the game!’ – without sniggering. To understand the pre-first world war world that formed such values, we might recall an anecdote from Robert Graves’ Goodbye to All That. On his way from Waterloo to Godalming, to start a new term at Charterhouse, the young Graves neglected to buy a train ticket. When he informed his father of this fact, Graves senior immediately went to Waterloo, bought a single to Godalming, and ripped it up.

Johns and Buchan, and many others like them, really did believe in, and argue for, the attractive and heroic vision of the British gentleman set out by the Spanish-American philosopher George Santayana: ‘a steady and sane oracle amongst all the deliriums of mankind. Never since the heroic days of Greece has the world had such a sweet, just, boyish master. It will be a black day for the human race when scientific blackguards, conspirators, churls, and fanatics manage to supplant him.’

Comments