The ghost story is a literary form that favours brevity. Its particular emotional effects — the delicious unease it creates, the shapeless menace and the unsettling uncertainty — work particularly well in concentration, as both Henry James and M. R. James knew so well. A ghost story does not need distractions.

Susan Hill has already established herself as a distinguished modern exponent of the genre with The Woman in Black and The Man in the Picture. She returns to it in her latest novel — or, rather, novella, The Small Hand. It is set firmly in the present, in a world with emails and trips to New York; but, as so often with a ghost story, it is also full of echoes from the past.

Adam Snow, the possibly unreliable narrator, is an antiquarian bookseller. One summer evening, he loses his way in the Sussex lanes and stumbles into the ruined garden of an apparently derelict Edwardian house. In the gathering dusk, a small child briefly takes his hand in a way suggesting that Adam is an adult whom the child trusts implicitly. The hand feels unmistakably real. But the child is not there.

The entire narrative unrolls like a carpet from this one moment at the end of the first chapter. In its impact, the carefully constructed episode recalls the point in W. W. Jacobs’ classic ghost story when the disembodied monkey’s paw writhes in the hand of the man that holds it.

Adam is drawn back to the garden, which, a generation earlier, had been a showplace of garden design, and which Adam himself and his family had visited when he was a schoolboy. The woman who owned it is still alive, as decayed as the garden, and equally marred by tragedy. He discusses the matter with his elder brother, who accompanied him on the family visit.

Meanwhile, in his professional life, he is pursuing a Shakespearian First Folio for a wealthy client, a quest that takes him from the Bodleian to a remote Alpine monastery. But the small hand will not leave him alone. Its invisible owner is no longer confiding. The hand’s intentions are increasingly hostile.

This beautifully written novel may be short, but not a word is wasted. The very name of ‘Adam Snow’ is full of symbolism, with its conflicting suggestions of the fallen man and unsullied purity. In common with many protagonists of ghost stories, Adam is emotionally incomplete. It is this, we sense, that makes him vulnerable. The sinister child, the rotting mansion, the monastery and the old books are of course familiar gothic props; but Susan Hill uses them to lend depth, as an expert cook uses familiar ingredients to enrich a new recipe, and draws out new flavours from them in the process.

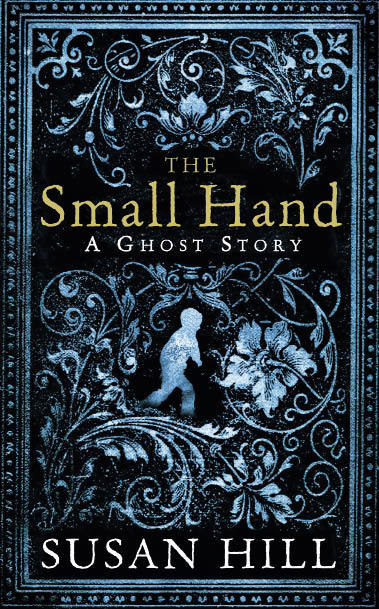

All in all, The Small Hand is highly recommended for a chilly autumn evening by the fire. And, as a bonus, the book has an exceptionally attractive cover.

Comments