In 1991, Moby folded the theme from Twin Peaks into a remix of his dance track ‘Go’ and a diminutive, teetotal, vegan Christian abruptly became the American rave scene’s first pop star. He was not the obvious candidate: one critic dubbed him ‘techno’s crazed youth minister’. As a showboating entertainer in a culture sceptical of stardom, and a somewhat sanctimonious puritan surrounded by hedonists, he put a lot of noses out of joint. On one early online rave forum the phrase ‘Go away Moby’ became a mantra.

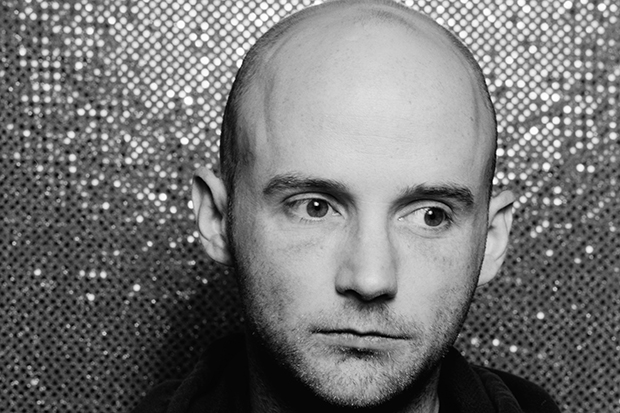

In his first memoir, Richard Melville Hall (nicknamed Moby due to his famous ancestor Herman) unpicks this paradox with an unusual degree of self-awareness and deadpan humour. Porcelain, which opens in 1989 with his first DJ gig and ends ten years later just before the release of his 12 million-selling electronic blues album Play, tells a quintessential Nineties story: the countercultural misfit becomes an unlikely star in a period of cultural flux, struggles to adjust to his new position and succumbs to predictable temptations.

You could say the same of Jarvis Cocker or Trent Reznor, but Moby’s faith frames this well-trodden path as a spiritual battle between purity and decadence. In one chapter he takes a breath of fresh air before DJing on a barge in Brussels. ‘The inside of the boat was like a Hieronymous Bosch painting, whereas outside was a quiet, bucolic night.’ Throughout Porcelain he observes the bacchanal with a mixture of repulsion and fascination, an astute anthropologist who isn’t averse to undertaking extensive fieldwork.

Moby doesn’t dwell on his childhood except to say that it was a mess. He loses his alcoholic father in a car accident when he is two and grows up poor and alien in middle-class Connecticut. A teenage alcoholic, he becomes a straight-edge Christian in 1987. Rave culture may seem like an unwise avenue for someone obsessed with rigour and self-control but to Moby it represents utopia. He is ‘reborn, unashamed and happy’ and captures that feeling in emphatically uplifting music. It can’t last. On New Year’s Day 1995, exactly halfway through the decade, he begins drinking again and embraces promiscuity with a vengeance. The observer of debauchery becomes a participant and he doesn’t feel as bad about it as he thinks he should.

Four hundred pages about a DJ/producer’s moral dilemma could easily be, to quote a damning review of his flop 1996 album Animal Rights, a ‘Great White Wail’, but Moby is an engaging writer. He says of Connecticut: ‘Happiness in New England had been suspect unless football or alcohol or money was involved.’ His hero David Bowie speaks like ‘Michael Caine crossed with a calm velociraptor’. Diana Ross’s disco song ‘Love Hangover’, which transfixed him as a child, ‘was a futuristic song on the radio, and neither the radio nor the future had ever betrayed me’. Moby milks a great deal of comedy from the tension between his highbrow and lowlife inclinations. A chapter which quotes Descartes and Rimbaud is followed by one in which he briefly becomes an apprentice dominatrix named Master Bobby.

One might attribute some of the detail and dialogue to artistic licence — each chapter is an extended anecdote — but Moby’s uncannily sharp recollection of what he was reading, hearing and eating at any given moment earns the reader’s trust. Most striking is his olfactory memory. He finds the hygienic aroma of dry cleaners and post offices comforting but plies his trade in grimy clubs in ungentrified early 1990s New York and lives in an apartment that reeks like ‘deep-fried cats’. He is constantly pivoting between the clean and the unclean; transcendence and squalor.

What makes Porcelain so refreshing in the crowded field of rock memoirs is its kindness. Peevishly judgemental as a young man (‘I was Christian, but I was also a dick’), Moby is much more understanding now. There are no real villains here and Moby’s brand of self-criticism is less punitive than the tedious self-flagellation of the post-rehab memoirist. He can even describe having sex in a toilet a week after missing his mother’s funeral and make it seem almost sweet, or at least forgivably human. Moby spent a long time pursuing clarity and redemption but it’s his fallibility that resonates.

Comments