Do you remember the first wave of hygge, in 2015? It seems a long time ago — back in the freewheeling technicolour of a pre-Covid world — but at that time hygge was the hottest thing to come out of Denmark. The country already attracted envy for its vigorous welfare state, covetable knitwear and high rating on the international happiness index, but the new export outshone them all. It roughly translated as ‘cosy’, people said, but the English word was frail and puny next to the soul-feeding, friendship-cementing, quasi-spiritual force that was hygge. The latter signified home-baked bread and cakes, hand-knitted socks and friends laughing around a wooden dinner table as a hotpot bubbled on the stove.

It was a feeling, a philosophy, a way of life, and the publishing industry went nuts for it: there was The Little Book of Hygge by Meik Wiking; Hygge: The Danish Art of Happiness by Marie Tourell Soderberg; and The Book of Hygge: the Danish Art of Living Well, by Louisa Thomsen Brits, among others. Wiking, an attractively rumpled, bearded Dane who runs the Happiness Research Institute thinktank in Copenhagen, spent a significant chunk of his book discussing the importance of low, diffuse lighting. One achieved this with well-placed lamps creating ‘caves of light’, he said, and a plethora of candles: ‘When Danes are asked what they most associate with hygge, an overwhelming 85 per cent will mention candles.’

One of the paradoxes of the hygge craze was that — although officially dismissive of vulgar consumerism — it was stupendous at selling us things. Not just books and candles, but rustic side tables, alpaca blankets and charmingly irregular pottery mugs. You could hardly hear the log fire crackling for the dinging of cash registers. Of course, like all popular movements, it spawned its begrudgers. It was enforcing conformity, some people said, with its instructions to keep politics away from dinner-table chat. You’d get lardy from all that cake. The Danes were suffering a disproportionate number of respiratory problems and house fires from their obsessive candle-burning. And anyway, there were now some cracking trends coming out of Sweden, such as lagom, the art of leading a balanced life, and fika, the life-changing Swedish coffee break.

With time, hygge calmed down, shifting from the white heat of publishing mania to the gentler terrain of familiarity. In 2017 the word entered the Oxford English Dictionary. It made regular, lower-key appearances in homeware catalogues and Sunday supplements. But then came the pandemic, and hygge came back, bigger than before. This time it ate the world.

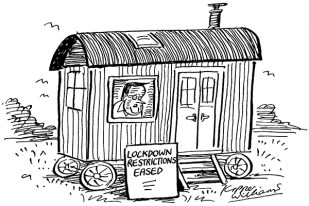

Unlike the second world war, which propelled British people out of their houses and into trucks, fields and hospitals, the Covid-19 pandemic is like a crisis designed by introverts. Aside from the heroic band of key workers who have kept the country going, the rest of us were instructed to fight the enemy simply by staying in. Pubs, cinemas, parties, concerts, all padlocked. Walks, for an hour a day. Apart from that, home. And working from home.

I’ve always liked staying at home, though in adulthood I generally prefer it to be optional. But as a child my two favourite words — rarely heard — were ‘snowed in’, closely followed by ‘power cut’. I was a fan of hygge before we even knew the word for it. What could be better than to be contained indoors, I thought, reading and drinking Campbell’s tomato soup, or navigating the house solely by oil lamp and candlelight?

Lockdown, of course, is the biggest mass house arrest in living memory. But for those of us with an instinct for domestic cosiness — the type who come alive at the sight of an Edinburgh Woollen Mill — it’s been like sticking someone with a penchant for cocaine in a 1980s Wall Street investment bank. It didn’t stop at candles. Next came the ‘heated throws’: plug-in electric over-blankets that you could gently roast yourself under. I got two for our house, and a large double dispatched to my parents in Belfast. At the back of my mind was the thought that even if the boiler broke, as its strained gurgling threatened, we could all huddle under these heat sources. ‘Pennies to run,’ I boasted. The children weren’t listening: they were in the kitchen, churning out sponge cakes and plaited loaves.

For us cosy types, lockdown is like sticking someone with a penchant for cocaine in a 1980s Wall Street bank

I had thick woollen socks, of course, but then I went one better: into a pair of sheepskin–lined house-boots from an excellent shop called House of Bruar, which seems to specialise in cable-knit coatigans for people who live in crofts or freezing baronial halls. When I ventured outside it was in a knee-length, hooded duvet coat, with a Thermos flask full of piping tea in my backpack. This is not my usual London winter-wear, but since lockdown abolished the concept of ‘external interiors’ — a shop, a café, a friend’s house — I had to take the hygge everywhere with me.

A record number of Londoners are buying homes in the country, apparently, but even more save themselves the effort by simply acting as if London is the country: striding around in hiking boots and waxed jackets, barking at their newly acquired dogs. The straggling band of ‘influencers’ who are marooned in Dubai in minuscule swimwear, dolefully nursing giant cocktails, have been bemused at the waves of public anger coming their way, but they’ve missed the zeitgeist. Abroad is out. Competitive cosiness is in. The thing now is to tweet a picture of your whisky glass and slippers next to a roaring fire, with the caption: ‘Friday night!’

The question now is: can we ever get out of it, even as the days lengthen and spring stirs? One day I know the door will open, and someone will say: ‘Are you coming?’ ‘Where?’ ‘To a party.’ ‘Are we allowed?’ ‘Yes.’ I’ll struggle to get up from the sofa, but my body — now 90 per cent pastry and wool — won’t let me. ‘Another time, maybe,’ I’ll murmur, settling back into a nest of blankets with my book. And somewhere, from behind a row of flickering candles, I’ll hear something sly and unsettling: the sound of hygge laughing.

Comments