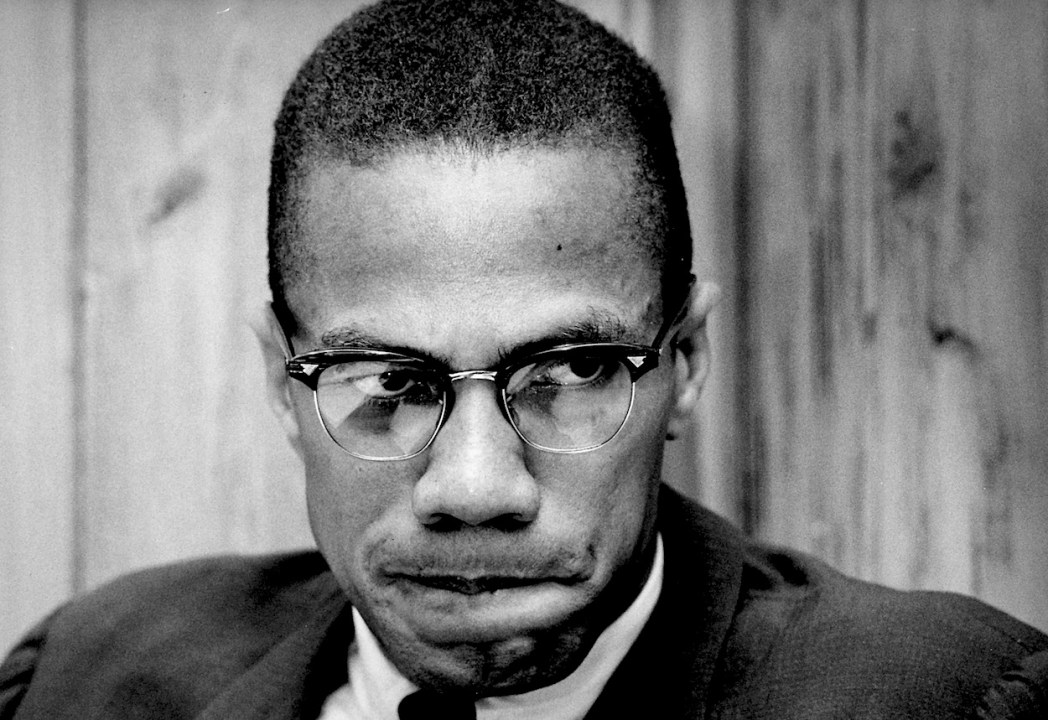

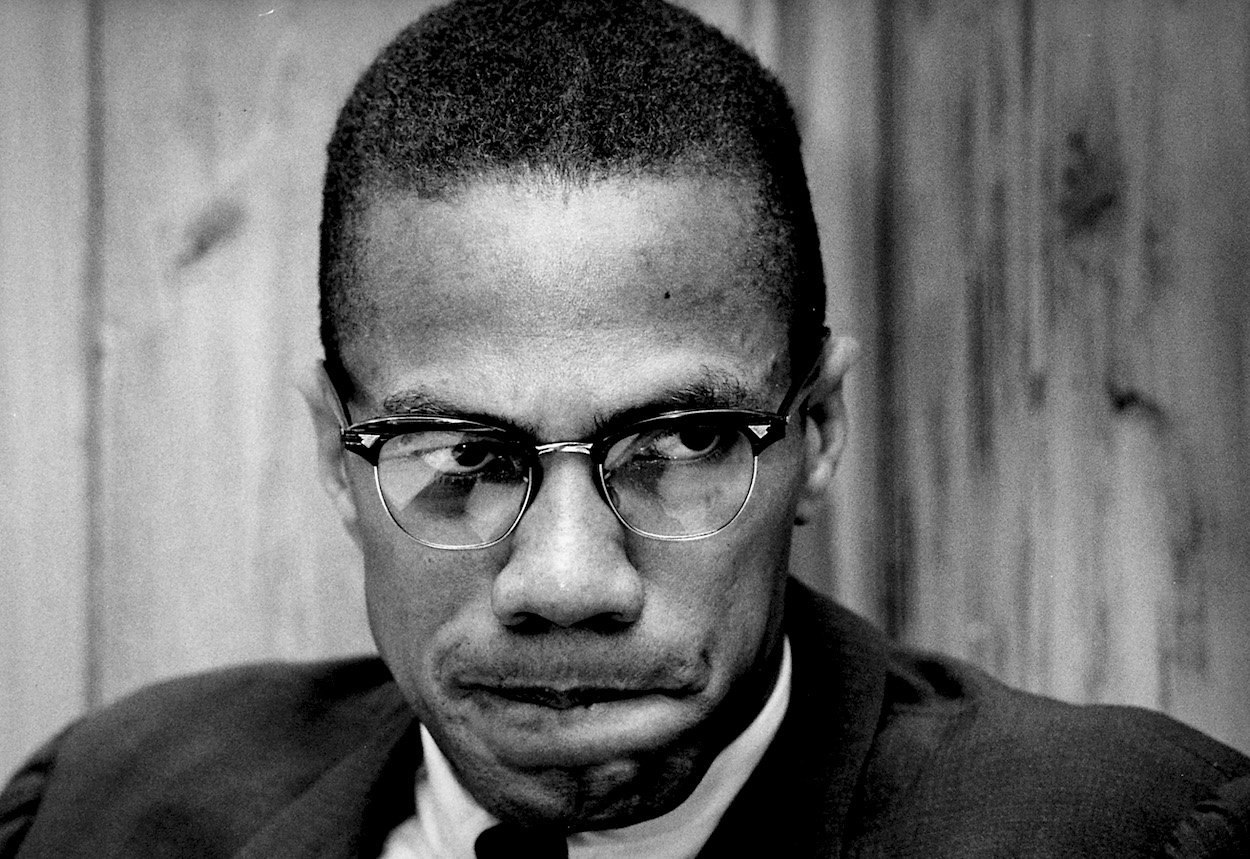

Five years ago, following the murder of George Floyd, a ‘racial reckoning’ shook the West. For some it was a time for our part of the world to come to terms with the reality of racism and to address the legacy of white supremacy. For others the protests following Floyd’s death poured petrol on the fire of the culture wars; racial divisions became reified and Britain was intellectually colonised by our American overlords in a spectacle of futile kneeling, black squares, virtue signalling and gesture politics. What I saw during that period, however, was the ghost of Malcolm X, haunting our times like Banquo at the feast. He was born 100 years ago this year, and his legacy is worth reconsidering during this Black History Month.

In an article in May, the Times columnist and Conservative peer Daniel Finkelstein described Malcolm X’s legacy as altogether negative. Finkelstein said that Malcolm X, who went from Nation of Islam (NOI) spokesman to black cultural icon, was the precursor to today’s ‘woke’ sensibility. ‘His was an identity politics,’ Finkelstein wrote, ‘seeing himself as black first rather than as American first. His chief criticism of capitalism was that it was racist and he stressed the extent to which American wealth was derived from the original sin of slavery. A main demand was for reparations. He played a role in making Palestine a left cause and brought political Islam into the western left. The rather odd alliance between conservative religion and socialism owes a lot to Malcolm X.’

Stanley Crouch, the irascible jazz and cultural critic, made similar points to Finkelstein decades prior to the turmoil of the 2020s. While Crouch himself once dabbled in black nationalism, he saw it as silliness at best, an appropriation of Herderite nationalism at worst. (Johann Gottfried von Herder said the ‘volksgeist’, or ‘spirit of the people’, i.e. culture, language and customs, defined the nation state.) For Crouch, the consequence of Malcolm X and Black Power was identity politics: women, gays and other minority groups choosing separatism over commonality. These movements ran counter to Crouch’s prized Omni-Americanism, which came from the universalist tradition of his mentors Ralph Ellison and Albert Murray. John McWhorter, the linguist, academic and cultural critic, a self-described ‘cranky liberal’, albeit of a contrarian disposition, wrote a provocative piece arguing that he would like to delete Malcolm X from history. To him, Malcolm X’s influence bred a victim complex and separatism that hindered Black America’s advance in the 1960s.

But is what Finkelstein, Crouch and McWhorter allege correct? There are aspects to Malcolm X’s legacy that run counter to their charges. Most obviously: Malcolm X came to reject some of the noxious attitudes that he promoted while an NOI spokesman. After breaking from the group, and after his pilgrimage to Mecca, he rejected ‘sweeping indictments of one race’, and wrote in 1964: ‘I wish nothing but freedom, justice and equality, life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness for all people.’ In his memoirs, he expressed regret for some of the views that he held towards white people, and saw that it was possible for blacks and whites to have ‘brotherhood’.

Other parts of Malcolm X’s thinking jar with the view that he was a prophet of woke. He was no fan of white liberal paternalism, for instance. (And what is wokeness if not white liberal paternalism?) In one speech before his break from the Nation of Islam, he said: ‘The American Negro is nothing but a football and the white liberals control this mentally dead ball through tricks of tokenism: false promises of integration and civil rights. In this is profitable game of deceiving and exploiting the American politics, those white liberals have willing cooperation of negro civil rights leaders. These “leaders” sell out our people for just a few crumbs of token recognition and token gains.’

And what of those ‘token gains’? Look at affirmative action. The prominent argument advanced in favour by Ronald Dworkin, that affirmative action is a good thing because the presence of black people at university might help white people, would be anathema to Malcolm X. Rather than genuinely advancing equality for black people, it treats black people as footballs or pawns in a game – a means of status signalling for whites. They are not subjects, but objects.

Malcolm X preferred black self-help to white tokenism

Malcolm X preferred black self-help and self-improvement to white tokenism. In an interview when he was a spokesman for NOI, he said: ‘The only way our problems will be solved is when the black man wakes up, cleans himself up, stands on his own feet and stops begging the white man and takes immediate steps to do for ourselves the things that we have been waiting on the white man to do for us.’ Hedonism, licentiousness, drugs and alcohol were to be rejected. Thrift, abstinence and sexual continence were the orders of the day (even if this didn’t apply to Elijah Muhammad, the leader of NOI).

After Malcolm X left NOI, his thinking developed on this path: ‘The American black should be focusing his every effort towards building his own businesses, and decent homes for himself. As other ethnic groups have done, let the black people, wherever possible, however possible, patronise their own kind, hire their own kind, and start in those ways to build up the black race’s ability to do for itself. That’s the only way the American black man is ever going to get respect.’

If blacks can advance and succeed regardless of white racism, then it follows that the elimination of white racism is not necessary for black people to advance. This counters the woke view that disparities between races can be reduced to oppression and white supremacy, which is the intellectual basis for much of the identity politics and political correctness that Finkelstein objects to. Malcolm X’s black nationalism is not woke (as we would understand the term today). If anything, it aligns with much of today’s black conservatism. This might seem strange, but both Elijah Muhammad and Marcus Garvey, the founder of black nationalism, were heavily influenced by the educator Booker T. Washington, whose Up From Slavery owed more to Samuel Smiles than to radicalism, whose accommodationism saw him feud with W. E. B. Du Bois, and who Ta-Nehisi Coates would go on to describe as ‘arguably the most effective and powerful black conservative in this country’s history’.

Coates also argues that Malcolm X himself was a black conservative. Maybe that’s too far, but at the very least he was an inspiration to a generation of them, Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas being the most famous. Thomas is a hate figure to the left and to many black Americans, but a strange irony is that one of his personal heroes is Malcolm X. When Thomas was a student at Holy Cross, he had a poster of Malcolm X on his wall and could recite his speeches from memory. The young Thomas supported the Black Power movement, Black Panther leader Kathleen Cleaver and the communist Angela Davis.

This was not passing teenage radicalism. In 1987, Thomas, then chairman of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, said: ‘I don’t see how the civil rights people today can claim Malcolm X as one of their own… Where does he say black people should go begging the Labour Department for jobs? He was hell on integrationists. Where does he say you should sacrifice your institutions to be next to white people?’

Look too at Shelby Steele, the author of White Guilt and The Content of Our Character. Steele – a Republican ensconced in the Hoover Institute – has travelled some way since his days as a student and a supporter of the Black Power movement. Yet he has described Malcolm X as one of his heroes and admitted that he loved him more than Martin Luther King.

For Steele, white guilt is a consequence of the 1960s when white America lost moral authority following the civil rights movement. It is not genuine guilt, but a wish to be absolved of racism, and consequently it encourages black victimhood. In turn, in Steele’s view, white guilt ‘spits out’ a black leadership who are reliant on it for status and money. They do not care about the real challenges facing black America. One need not fully agree with Steele to see the prescience of his thinking in an era of ‘white fragility’ and ‘woke capitalism’.

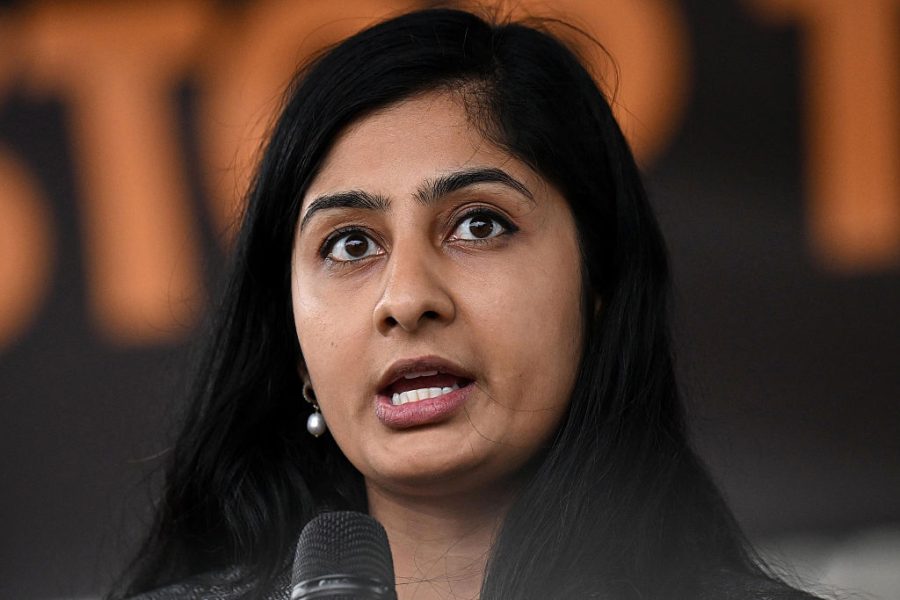

Steele attacked black leaders for using white guilt for financial gain

Steele says the main challenge for Black America is not victimhood but development, and the focus on victimhood undermines development. In a criticism of black leaders such as Jesse Jackson (who he voted for in 1988), Steele claimed that he and other civil rights organisations were focusing on white guilt as opposed to focusing on agency, development, and a moral and cultural transformation of Black America. Steele attacked black leaders for using white guilt for financial gain, and for refusing to tell black people that they had to help themselves. Moral agency and cultural transformation are key to getting ahead; begging down at the church of racism is bad. (Ironically, despite echoing Malcolm X, Steele was parodied by the director Spike Lee as an Uncle Tom.)

Many other black conservatives – Walter Williams, the economist; Ward Connerly, who successfully organised California’s Proposition 209 prohibiting affirmative action; Glenn Loury, who coined ‘social capital’ in 1977 to explain racial inequality in America – were or are admirers of Malcolm X, and there may be something in their thinking that we should take seriously. The answer to black disadvantage in this country and in the United States might not be found in futile protest, virtue signalling or merely decrying white racism. Black people can succeed and overcome adversity, and resilience and agency should be prized.

Reaching a more rounded view of Malcolm X requires us to consider him outside our contemporary ideas of ‘wokeness’, and would allow us to see other aspects of his legacy. It is not even necessary for one to embrace the politics of Thomas, Steele, Williams and others to recognise this. One may counter understandably that their thinking could venture into ‘blaming the victim’. Some may warn that their views could be distorted to deny the reality of racism, the legacy of white supremacy or pretend that structural constraints play no role in one’s fate. This concern is justified and ought to be acknowledged. But by removing black people’s agency over their own lives, you erase their humanity and dignity, reducing them to perpetual victims in need of white liberal patronage. Might this not lead to a more paternalistic form of racism, a bigotry of low expectations, another form of white supremacy?

Comments