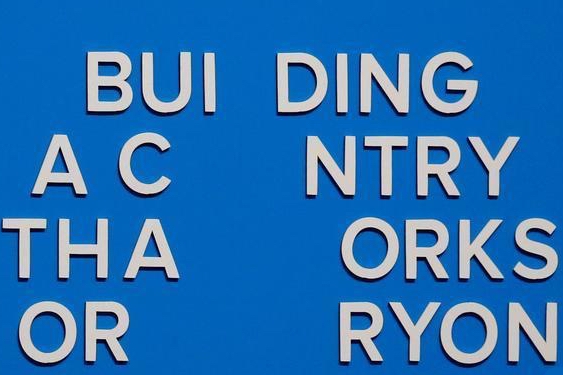

Theresa May’s conference speech — interrupted by coughing fits and with part of the set falling apart behind her — served as an unfortunate metaphor for her premiership and party. She is carrying on and in doing so, she demonstrates her resilience and sense of duty but also her frailty. The horrified faces of cabinet members watching as her voice dried up on stage seemed to sum up their wider concerns about whether their party is in a fit state to see off Labour, a party they so recently dismissed as a joke. Now, they are left wondering if their party is falling apart.

https://twitter.com/bbcdaniels/status/915545386407866369The Prime Minister spoke about taking the fight to Jeremy Corbyn, but her announcements suggest that she is suing for peace — accepting his argument, and seeking to copy some of his solutions. The Conservatives are talking as if they have the right answers, but acting as if they have none. They are diagnosing problems, but are strikingly unable to come up with solutions of their own, and they are looking very much like a party that is running out of ideas and options.

The main pledge from this conference was to build more social housing — but the UK already has more than almost any other country in Europe. The housing crisis is created by the lack of private supply, itself a function of the broken land market — and the many political disincentives to build. Far from being a ‘market’ crisis, the housing problem is a typical example of the failures of government — and what happens when something essential is needlessly rationed.

There is no shortage of Tory MPs who know what needs to be done: the problem of planning permission refusals needs to be dealt with — along with local councils that are anti-development. This is the only way to increase the amount of private housing. But instead, Mrs May is increasing demand by pouring more money into the help-to-buy scheme of state-subsidised mortgages. Again, most of her MPs know that this is at best a gesture that will help only a small number of people. The overall effect of help-to-buy will be to make houses even less affordable, intensifying rather than relieving the problem.

Her tuition fee change, lifting the loan repayments threshold from £21,000 to £25,000, seems to concede the general point to Jeremy Corbyn. Is it unfair to ask students to bear more of the cost of their tuition? David Cameron thought not; even the -Liberal Democrats thought not. Students seem to agree that the loan (which most will never be asked to repay in full) was worth taking out in exchange for a degree. Students from deprived backgrounds are applying to university in record numbers: there is no sign of students being deterred.

A bold Conservative party would have stood its ground. Perhaps there would have been more mention of how the new fees system transfers money from wealthier families to poorer ones, as so much of the fee money is used by universities to support students facing hardship. It was never going to be a popular argument, but a government ought to take unpopular decisions — and seek to persuade the voters. Instead, the Tories seem to be on the run. They seem to agree with Corbyn that the fees system introduced by David Cameron is iniquitous, and the only question is how much to water it down.

After seven years in power, too many Tory ministers have begun to think like civil servants — seeing problems, not solutions. They have become technocrats rather than communicators. They have forgotten how to make and win arguments. But with politics becoming a battle of ideas once more, the Tories need ministers who can make the case for the market economy, and demonstrate what they mean through policies —and defeat Labour by talking about the world we live in today, rather than about the 1970s and the IRA.

The Tories now seem split between the fatalists who think that Britain is moving left and so the only option is to adopt ideas that they once opposed, and the optimists who think that now is the time to make the case for Conservatism. Boris Johnson gave his party a demonstration of optimism in his conference speech. And Ruth Davidson noted that the remarkable revival of the Scottish Conservatives only began when they stopped apologising for being Tories and started to make their arguments with passion and conviction.

It’s unlikely that either Johnson or Davidson will become party leader. He has too many enemies amongst his own parliamentary colleagues, and she seems wedded to Scotland, her own discomfort zone. But before the Tory party decides who should replace Mrs May, it needs to decide what type of Conservatism to pursue: whether it wishes to go along with Labour ideas, or present voters with a radical and coherent alternative.

It’s strange to think that about six months ago, the Conservatives were looking forward to at least ten more years in power and to an election that would destroy rather than merely defeat the Labour party. Now they are facing an existential crisis — one made all the more vivid by the unimpressive party conference and the speech that ended it.

Comments