I love a good hard debate, especially at a university. I can’t recall how many such clashes I have had, on God, free speech, marijuana, and Russia. But on the subject I really want to talk about, the destruction of the grammar schools, I find it harder and harder to get anyone to debate against me. Your guess is as good as mine about why the comprehensive school enthusiasts won’t argue with me anymore (they used to). It is certainly not that nobody cares about this ancient controversy. They do. A few years ago one university society tried for months to find me an opponent, and couldn’t – yet hundreds still turned up to the one-sided meeting we eventually decided to hold.

Two political parties were prepared to destroy – irrevocably – more than 1,200 proven grammar schools to make the new comprehensives possible

That university – York – was the one I attended myself in the early 1970s, when the dissolution of academically selective state schools had begun but was far from complete. I have since checked the archives and they confirm my memory, that many of my fellow undergraduates, at what was then a small and very selective plate-glass establishment, were young men and women from modest homes and first-class state schools. No egalitarian algorithms had been used to choose them. They were just very well qualified, thanks to good teaching. It also helped that the Vice-Chancellor in those days was Eric James, Lord James of Rusholme, a proper old-fashioned Fabian socialist. He had previously been the High Master of the mighty Manchester Grammar School, and was ferociously proud that it educated so many manual workers’ sons during his time in charge.

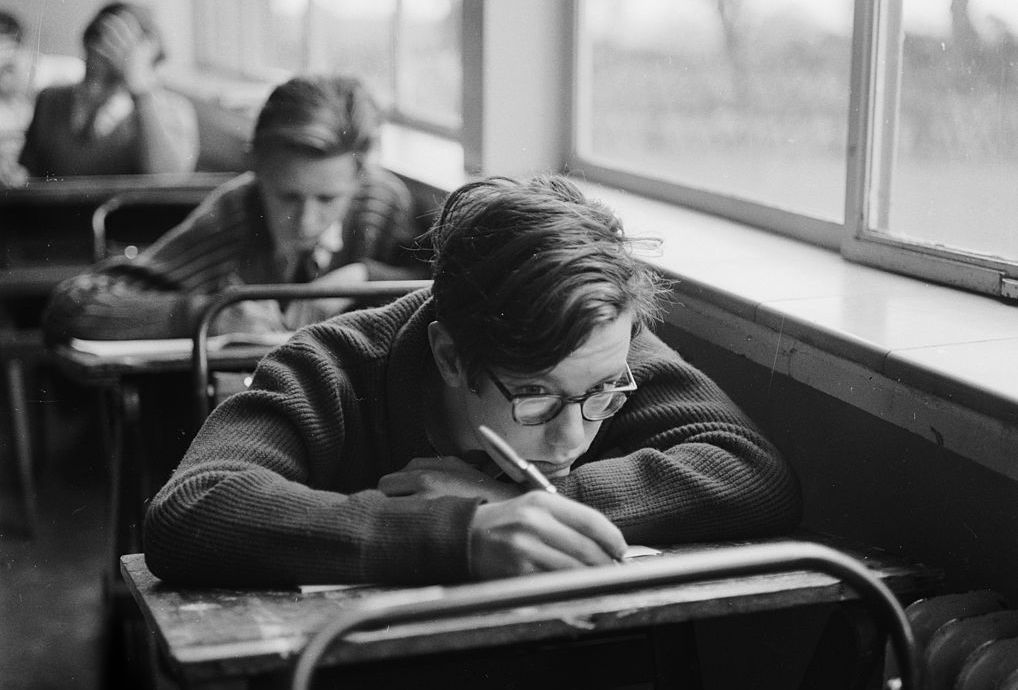

At that time, I was clueless about what was going on in British education, as we so often are about the great events of our own younger years. It did not help that I was myself a public school drop-out and a Trotskyist, great obstacles to understanding those momentous events. It took many years to grasp that I had witnessed the last full flowering of a very good and noble thing. Its huge impact on every part of our society is easily revealed by a study of ‘Who’s Who’. You will find it packed with scientists, military commanders, judges, civil servants, politicians, authors and actors who attended grammar schools between 1944 and the late 1960s.

Probably the effect is understated, because so many will have come from Scotland, where it is much harder to tell if someone attended one of the many superb selective secondary schools north of the border, which were not generally called ‘grammar schools’ but were much the same. They were abolished there by a single ruthless decree – Circular 600 – in 1965.

On both sides of the border, the strangling of the selective schools also killed off a brilliant and successful partnership between private and public sectors, ‘Grant-Aided’ schools in Scotland and ‘Direct Grant’ schools in England. Such schools charged fees to those who could pay, but also took in many more bright state school children, without fees, thanks to the taxpayer. But without academic selection to sustain it, the scheme was finally killed by Labour’s Fred Mulley in the middle 1970s.

Not that Tory politicians come out of this story any better. You get the impression that few of them used state schools of any kind, or much cared. The famous 1944 Education Act. Credited to the Tory Rab Butler, was a remarkably cheap way of looking progressive and modern. Evelyn Waugh grumpily complained that it was ‘a scheme for giving education away free to the deserving poor’, which we have to suspect was something he disapproved of. Certainly it robbed many less well-off middle class families of an affordable type of private education. From 1944 onwards, their children had to compete against the working class in the 11-plus test for Grammar School places – places their parents could once have bought. The 1944 Act, paradoxically, also legalised state comprehensive schools for the first time, and many of these would be created in the early 1960s under Tory governments and by Tory local authorities. This happened especially on new housing estates, where providing two different sorts of secondary school was expensive. The Tories also did very little to anticipate the effects of the huge post-war baby bulge, which were completely predictable and had been sweeping through primary classrooms for years. When the population wave hit the secondary sector in 1956, there simply were not enough grammar school places for those who deserved them. Provision had been patchy and often inadequate in the first place. Now the 11-plus exam, never much-loved, began to be seriously unpopular, and the Utopian pro-comprehensive zealots (who would replace the 11-plus with a far more brutal system of selection by wealth) finally won an audience in the wider electorate. By 1958, Labour’s leader, Hugh Gaitskell – a Wykehamist who must have known better – was claiming that comprehensive schools would mean ‘a grammar school education for all’. This dim slogan, much like a certain shop’s claim to be ‘exclusively for everyone’, successfully stopped people from thinking.

Two extraordinary things were true by 1964, when this became an important election issue. The first was that nobody knew what the comprehensives would be like. Yet as it turned out two entire political parties were prepared to destroy – irrevocably – more than 1,200 proven grammar schools to make the new comprehensives possible. The other is that the secondary modern schools, attended by the majority who did not get into grammar schools, were nothing like as bad as we are nowadays told and were probably better than most modern comprehensives. We owe this knowledge to a superb, subversive book on the subject Secondary Mod, by Dick Stroud, who went to such a school and won a place to study physics at the University of Sussex in the tough days before university expansion. And yet the change went ahead and the grammars – and the standards they had maintained – were wiped from the map. The schools which are still called by this name bear little resemblance to the pre-revolutionary grammar schools. Like the private schools, they waltz through devalued exams designed for the low attainments of comprehensives, and so look far better than they are. We lost a lot more than a few hundred schools. We lost our standards. Astonishingly, the former era of honesty and rigour lasted barely 20 years. Yet it still shines so brightly that anyone who thinks about it must be tempted to weep that it has gone.

Peter Hitchens is a columnist for The Mail on Sunday. His book on the destruction of the grammar schools ‘A Revolution Betrayed’ is published this week by Bloomsbury.

Comments