Michael Kennedy, who died on New Year’s Eve, was the Sunday Telegraph’s music critic when I was for a while assistant arts editor there about 20 years ago. He was of course musically knowledgeable beyond reproach, but his writing had the compulsive readability of a man who was always a journalist, a storyteller.

He was elitist in his taste but populist in his communicative instincts, something that I rapidly absorbed as I subedited his copy. Critics are usually obsessively protective of their work, often wounded by disagreement rather than stimulated. Kennedy was an exception, robustly open to the possibility of others improving and developing work he could get nowhere with.

One Sunday in 1992 he produced an extraordinary article about Edward Elgar – of whom of course he was a major biographer. The Sunday Telegraph arts editor, John Preston, headlined it ‘The mysterious Mrs Nelson’. It concerned Kennedy’s so-far frustrating search to locate a cook, a Mrs Nelson, whom Sir Kenneth Clark had reported had borne a daughter by Elgar. There was considerable anecdotal upholstery for the story – there had been gossip in musical circles, among composers and critics alive at the time, many of them close to Kennedy.

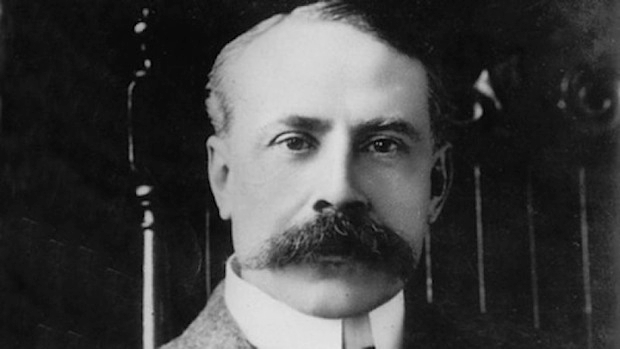

The crucial piece of evidence was a letter from Clark to Kennedy, in which – 25 years after the facts – he recounted how he accredited documents for his cook’s daughter, as ‘Miss Elgar’. Kennedy (pictured below) had pursued further substantiation to no avail. He told John he would like to publish the story as far as he knew it – in the hopes that readers at the Sunday Telegraph might help contribute more information. John loved a cracking story, so up it went.

I subbed the copy, and in its aftermath I handled the letters that came in. One of them was from a man who believed he was the son of this Mrs Nelson. He had been separated from her a lot during his childhood, and had spent his lifetime trying to find out more about her. And he had an older half-sister, of precisely the right age. He knew nothing about Elgar, but the details he gave of his mother – her hair colouring and attractiveness, her skill as a cook, and her past in musical theatre – and of his awkward, less dynamic half-sister, all matched the recollections of Clark in his letter to Kennedy.

It was intensely exciting, and with Michael’s blessing I pursued this contact to see what more could be unearthed. I spent considerable time in the then St Catherine’s House where birth, marriage and death certificates provided a promising timeline for our Mrs Nelson. There were multiple corroborative suggestions in her poverty-struck Welsh past, her name, her parentage, the muddle and obstacles that this resourceful young woman had overcome to become a dancer in London, and in time a well-regarded cook. I found many of her job placements; with her son’s help, I discovered her tendency to make bad liaisons. Circumstantial evidence was strong indeed that this Dora Nelson had become, if briefly, Elgar’s mistress.

I discovered that the daughter, born in a home for unmarried mothers in Wimbledon, had the right dates to be connected with Elgar’s well-known psychological wobble in the mid 1900s. This was a turbulent period much probed by biographers and Elgarians, speculating on religious and sexual conflicts in the composer’s life. I managed to track this daughter’s life by official records through her own marriage, uneventful life, and eventual death only a few years previously to my research. She had no children. It was tantalising that we might just have missed Elgar’s illegitimate daughter.

With Michael’s enthusiastic support, and the increasingly useful resource of internet records, I set out these latest developments and deductions a few years ago in a too conclusive article in the critics’ website The Arts Desk. By now, taking into account a multitude of Elgarian detail, official documents, theatrical newspapers, biographies, Lady Elgar’s diary, musical documents concerning the mysterious dedications of the violin concerto and that unnamed Enigma variation, the accumulation of all sorts of details of place, events, contacts and psychology, it looked pretty good. About as conclusive as it could be, without quite being definitive. Michael and I thought from all the evidence that Elgar’s illegitimate daughter was very likely Dora Nelson junior, known as Pearl.

The beauty of online publication is that one can actively profit from our continuing appeal to readers to help in finishing this hunt. I was contacted after a while by a librarian, Andrew Baker. He is an amateur composer with a special interest in Lord Berners. Berners had been a clue in Kenneth Clark’s letter – Mrs Nelson had previously been Lord Berners’ cook.

Baker picked up the story, contacting Sofka Zinovieff, whose biography of Lord Berners was just reviewed in The Spectator last October. She knew about the cook, and put Baker on to a 1937 cutting from the Daily Express, in which Berners proudly introduced Mrs Nelson. A black and white photograph showed a strapping woman, no longer young, apparently with dark dyed hair and a big happy smile. The details of the article concurred with everything we had so far.

But then Baker, truffling with his librarian’s expertise through electoral rolls and documents, unearthed a huge surprise.

There were two Mrs Nelsons. While Nelson was not an uncommon surname (there was even an Edwardian music-hall dancer Dora Nelson who briefly diverted me in my quest for ‘my’ Dora), incredibly there were two documented Mrs Nelsons who were red-headed, high-class cooks with theatrical pasts, both hired in aristocratic houses in London in the 30s and 40s, of similar age, and both with single illegitimate daughters. Either of them could be eligible as Elgar’s mistress. But was it Dora or Lilian?

While I had been pursuing Dora Nelson (the name recorded by Sofka Zinovieff) it was Lilian Nelson whose name turned up at the bottom of a letter in the Tate gallery archive of Clark’s correspondence. Her letter to him directly related to the circumstances that Clark had recounted to Kennedy. This was conclusive that Dora, and her bereaved son, were red herrings.

Andrew Baker took up the story, and a still more pathetic tale emerged about the daughter, Mignon. (Both Mrs Nelsons’ daughters had evocative names – Pearl, Mignon.)

Mignon, her childhood fractured by war and the uncertainties of her mother’s life, became a Tiller Girl, who apparently suffered depressive illnesses, and made several suicide attempts. She finally succeeded in her late 30s. There is quite a bit out there about Mignon.

But the anchoring details that were numerous in Dora Nelson’s past life were much less discoverable in Lilian’s, and it has so far not proved possible to pin the mother down in bed with Elgar, as it were.

Baker’s assiduous work has unearthed a story that hardly needs the ghost of Elgar’s paternity to make it fascinating. But that ghost inevitably lingers. Unable despite all to beat the enigmatic mystique that Elgar cloaked himself with in life and in death, Baker has published his findings on his website, heardmusic.com.

Michael had reacted with delight to Baker’s investigations, which looked increasingly worthy of official publication. He emailed me: ‘Gosh! What a magnificent piece of research by Andrew and you. Please tell him I am overwhelmed with admiration. I feel this must be the truth… I read it through at a sitting and was enthralled. I would be honoured to write a foreword.’ He was eager, like a great reporter, to see the story nailed. He was eager, like a great editor, to see someone else do it if they could.

Comments