This is an economic horror show. According to YouGov, UK unemployment may have jumped five per cent in a matter of weeks. The consultancy CEBR estimates that global GDP may shrink by twice the rate seen in the Great Recession. This may be the worst hit to British people’s livelihoods since the Great Depression of the 1930s.

Except one thing is different: this is a deliberate economic shutdown, made necessary to avoid a deeper, more human one. It isn’t that the economy is failing to work because the credit system has seized up as in 2008. We are actively contracting productive work in order to limit a tragedy. A recession it will be, but it is our choice in a time of acute crisis, demanding Herculean lifting and leadership by the state. That puts it into a more modern category: degrowth.

Despite its current disastrous necessity, ‘degrowth’ has been championed by the environmental campaigners Extinction Rebellion for years. It means ‘planned economic contraction‘ or, in other words, deliberate ongoing recession. It relies on a flawed syllogism: economic growth has caused harmful greenhouse gas emissions; these emissions are causing climate change; therefore cut economic growth to stop climate change.

The degrowth logic is tempting. Economic growth took a sudden turn upwards in the nineteenth century with the industrial revolution and so did carbon emissions. In the financial crash, economic output dipped dramatically, and so did carbon emissions. Early data show that Chinese emissions have dropped by a quarter after the economic seizure caused by coronavirus. This is degrowth in action.

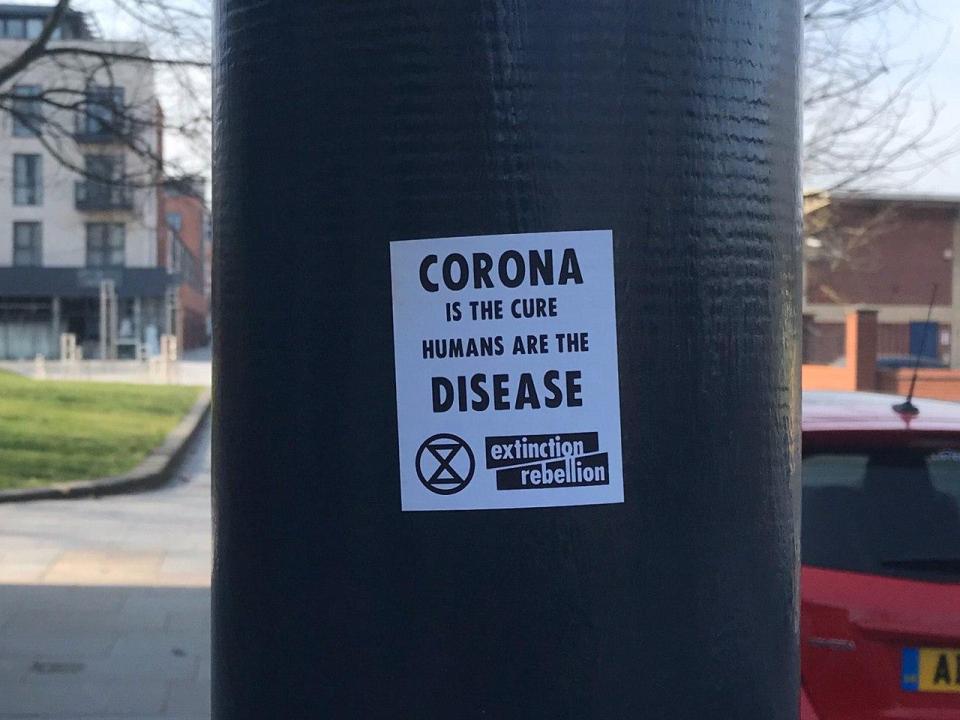

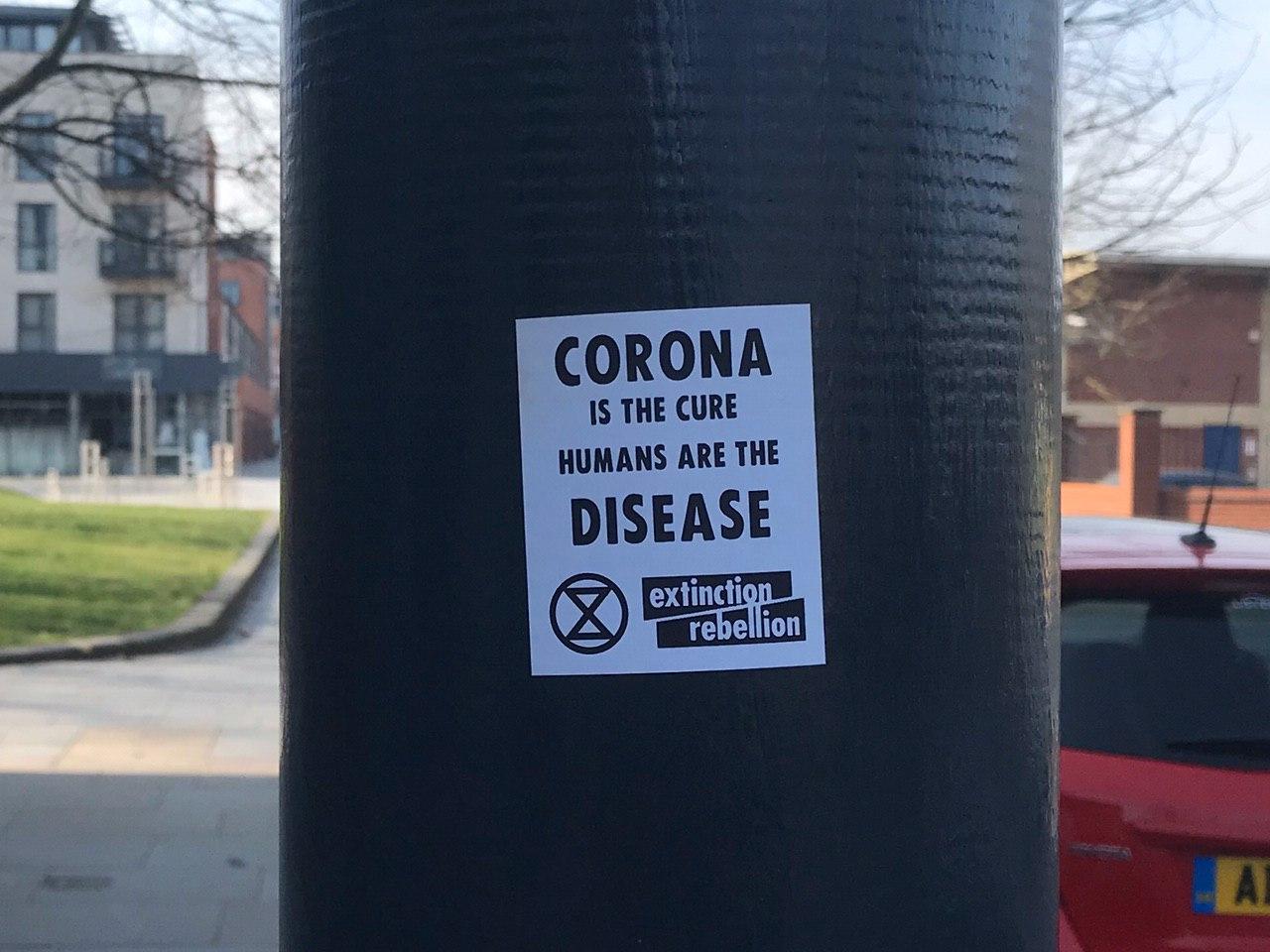

You will find this idea running throughout the Extinction Rebellion movement from its leadership to its decentralised, independent ‘cells’. Its founder has articulated his vision in which ‘we are going to have a reduction in living standards’. Another senior figure claimed that ‘we have to de-growth the economies of the West’. More recently, the movement’s East Midlands branch appeared to have gone even further to declare that ‘Earth is healing… Corona is the cure. Humans are the disease!’.

The current crisis is degrowth in practice, crippling our economy until the threat passes

We should note that the last of these sentiments has been strongly disowned by the campaign’s leadership, which claims the picture of the poster came from a ‘fake account’. It almost doesn’t matter; there is a pattern of behaviour here of saying unrealistic things and doing unreasonable things, often followed by a leadership denial. There are only so many times that activists, granted licence under the campaign’s open source model, can do unpleasant or illegal things and still be excused as rogue outliers. The leadership’s tactic of ‘enable, then disown if it goes wrong’ is disingenuous. More to the point, the East Midlands approach has simply taken a dangerous idea from the XR mainstream and made it even worse.

Environmental policy can learn plenty from the Covid-19 disaster. It provides a glimpse into a low-carbon future, where renewables are more reliable than oil, air quality is better, electricity grids are decentralised, commuting is less of a necessity and plundering ecosystems means opening Pandora’s Box. But we should add to that list an even broader lesson: degrowth devastates people’s lives.

With climate change, Extinction Rebellion offers a diagnosis, a prognosis and a prescription. Most people would agree with the diagnosis. We are happy to trust the scientific community’s high level of confidence that man-made carbon emissions are causing the atmosphere to heat up quickly.

We start to diverge on prognosis. How bad this will get in the future is complicated. There is fierce debate over the use of different modelling scenarios, especially one produced by the UN to denote an assumed ‘business as usual’ pathway, despite some highly unlikely assumptions. This has been used to skew debate towards alarmism, which then makes it harder to prescribe a policy response.

The prescription must be within the remit of politics and policy, with democratic, nuanced, informed and adversarial debate, culminating in parliamentary votes. Sidestepping this by creating hand-selected ‘citizens assemblies’ with legally binding powers, as Extinction Rebellion has demanded, is not likely to enfranchise the average person. Nor is telling people that their wages must get progressively lower, in line with a degrowth agenda. That will only provoke a backlash against the environmental agenda.

Instead, the UK has applied its genius for institutional design. In 2008, we created the Committee on Climate Change, a body of world-leading scientists who analyse the complex data on our behalf. The CCC makes recommendations and sets ‘carbon budgets’, leaving it to parliament to decide how to respond. This balance leaves science to scientists and politics to politicians, avoiding the grotesque cargo cult science seen in other legislatures. The system was used to commission the CCC’s Net Zero report long before Extinction Rebellion besieged London.

In addition, the UK has long been committed to carbon pricing, though it still has a long way to go – an economy-wide carbon price is needed. Carbon pricing drives a wedge between economic investment and emissions, making commercial profits dependent on emitting less carbon.

That is an exemplary institutional architecture, designed to maintain a political mandate for the process of decoupling emissions from economic growth, rather than risking political support with a policy of degrowth. It has allowed the UK to make the best of its economic resources; scientific, technological, institutional and financial. It allows profitable investment by following the curve set out by policymakers. It has made coal investment increasingly unattractive, not for altruistic reasons but for economic ones. Various renewable energy sources are now cheaper than fossil fuels. Carmakers are following the curve by releasing scores of new electric cars. Companies like OVO and Octopus are creating intelligent energy management systems that make your home more efficient and cheaper to run.

These are examples of decoupling growth from harmful emissions. You can see the longer-term trend in the data over time: since 1990, GDP has grown 179 per cent, whereas carbon emissions have dropped by 41 per cent. We are already doing decoupling, not degrowth.

Progress has been slow at first, measured in decades. Then things start to beat your assumptions. New technologies are smashing through cost and deployment expectations, whether it’s battery storage, electric cars or wind and solar. The energy analyst Michael Liebreich notes that replacing one major technology with another often follows this pattern:

‘The first one per cent takes forever; one per cent to five per cent is like waiting for a sneeze – you know it’s inevitable but it takes longer than you think; then five per cent to 50 per cent happens incredibly fast. Clean energy is entering this period of rapid transformation.’

This is economic growth. It means getting better, more productive, getting more from the work put in. As we increasingly design markets to limit emissions, the process will gather pace. Financiers will start to see the direction of travel, piling into the low-carbon technologies. Workforces will become more skilled and create faster systems. Progress will compound on progress. It is perfectly doable if we marshal our economic resources and let them bloom. In contrast, degrowth is a contraction of our economic apparatus.

The current crisis is degrowth in practice, crippling our economy until the threat passes. Let’s ensure it is temporary. On top of the lives lost, myriad jobs have been lost too, businesses broken, debts have racked up and progress in many areas has halted. People are worried about the future, but they know this crisis will pass and they can start to pursue their ambitions again.

In a long-term degrowth economy, the recession would be permanent. That is a recipe for misery and disaster. We should learn this lesson today and reject degrowth forever.

Comments