I like a book that can put its point in four outrageous words and use it as its title. Diana Souhami might be right. Without the women her book is devoted to, literary modernism would have looked very different. A consciously new approach to writing met a body of women who were being heard for the first time; the results were compelling. At the beginning of a novel by one of them, Gertrude Stein’s The Making of Americans, the terror of masculine traditions is concisely stated:

Once an angry man dragged his father along the ground through his own orchard. ‘Stop!’, cried the groaning old man at last, ‘Stop! I did not drag my father beyond this tree.’

If culture were ever to break those bonds of duty and repetition, it might be in the form of women, bonded primarily to other women, and creating objects in prose and verse never conceived of before.

Lesbian women had appeared in Victorian novels, but depicted in a characteristically indirect, deniable way — Dickens describing Miss Wade, for example, or Wilkie Collins’s Marian Halcombe. The law in England never took any account of lesbianism: it wasn’t, contrary to myth, Queen Victoria’s intervention, but the belief of the House of Lords that no woman would ever think of doing such things unless it was brought to her attention by legal proscription.

In French literature, the question had long been addressed with more clarity, at least as far back as Diderot’s La Religieuse; there are unambiguous lesbians in Balzac’s La Fille aux yeux d’or and in Baudelaire. It is sometimes thought that the many lesbian relationships in Proust are rudimentary translations of his male lovers’ heterosexual flings, but to me he seems fascinated by the secretive circles that Albertine and Andrée move in, and to have observed the reality of lesbian society very carefully.

Proust was fascinated by the secretive circles of Albertine and Andrée, and observed lesbian society very carefully

It won’t have escaped notice that all these examples are written by men. It wasn’t until the 20th century that lesbian women started not just writing from their own experiences, but publishing their writing. For the first time, they were in a position to live openly and play important parts in the literary world.

Perhaps encouraged by the long-standing openness of French literature towards their feelings, these women were drawn to Paris, where they made a stir. ‘Ils sont pas des hommes, ils sont pas des femmes, ils sont des Américains,’ Picasso said. Souhami’s book is about four of them, and the circles around them. Sylvia Beach was the founder of Shakespeare and Company in Paris, and the first publisher of Joyce’s Ulysses. Bryher was a poet and novelist, and the partner of the Imagist poet Hilda Doolittle, who wrote as H.D. Natalie Barney hosted the great Paris salon of modernism, living until 95 in an atmosphere of inexhaustible scandal. And Gertrude Stein was, of course, a novelist and early collector of Picasso, Cézanne and Matisse.

Two things are immediately apparent. The first is that most of these women were given the possibility of living openly by having independent means — sometimes as a result of immense inherited wealth. Bryher’s father left £36 million when he died in 1933, his legacy enabling her to live more or less as she liked — including building a Bauhaus villa at Vevey on Lake Geneva. She could also afford to heavily subsidise the one woman among them who didn’t have money of her own, Sylvia Beach.

The second point is just how many women mentioned by Souhami changed their names as soon as they were able. Pauline Tarn became Renée Vivien; Anne-Marie Chassaigne became Liane de Pougy. Girlish first names were easily dispensed with: Hannah Gluckstein became Gluck, Sidonie-Gabrielle Colette became Colette tout court, and Radclyffe Hall, who started life as Marguerite Radclyffe-Hall, went on to be known as John in private. The phenomenon wasn’t limited to lesbians. Cicily Fairfield early on saw how hopeless her birth name was for a woman writer of serious tendencies, and called herself Rebecca West, after Ibsen’s heroine. Like West, Bryher felt that ‘Annie Winifred Glover’ just wouldn’t do. They renamed themselves, and something new began.

Sylvia Beach had no idea how bookshops were run, or how books were published, and everyone was the better off for her ignorance. The first of Shakespeare and Company’s ‘bunnies’, as she called its abonnés, or subscribers, was André Gide, closely followed by Gertrude Stein, who demanded that The Trail of the Lonesome Pine and Gene Stratton-Porter’s A Girl of the Limberlost (‘a sequel to her earlier novel Freckles’) be stocked. Forever afterwards the shop was run in the interests of undeserving writers.

Nor would any publisher have allowed Ulysses to run out of control in the way it did (Souhami says that at least a third of the novel was added at proof stage, enormously increasing the costs). The sad aspect of Beach’s inexperience was that she relied entirely on Joyce, and when he understandably decamped to Random House in 1933 she was emotionally and financially bereft.

Natalie Barney wrote herself — some Pierre Louys-like amorous poems about same-sex love as early as 1900 — but her main significance was as a hostess, and impresario of scandal. Another lesbian hostess, the Princesse de Polignac, formerly Winnie Singer, may have been more culturally impressive, commissioning music from Ravel, Prokofiev and Stravinsky, but Natalie sounds more fun. She described herself without qualification as a lesbian, and may have been the first in modern times to convert a cult of Sappho into a visit to Lesbos — which, even in 1904, was not quite the paradise of myrtle groves and hyacinth gardens of her imagination. (‘An elderly woman cooked their food. Renée gave hers to the dogs.’)

Souhami’s account of Barney’s life, her many affairs and excesses, has a breathless hilarity as one duchess succeeds another in Barney’s passions. (‘In 1922, Liane de Pougy, who had risen up the social ladder to become Princess Ghika, formed a sexual threesome with Natalie and Lily’.) She was still picking up women on the Promenade des Anglais in Nice in her eighties.

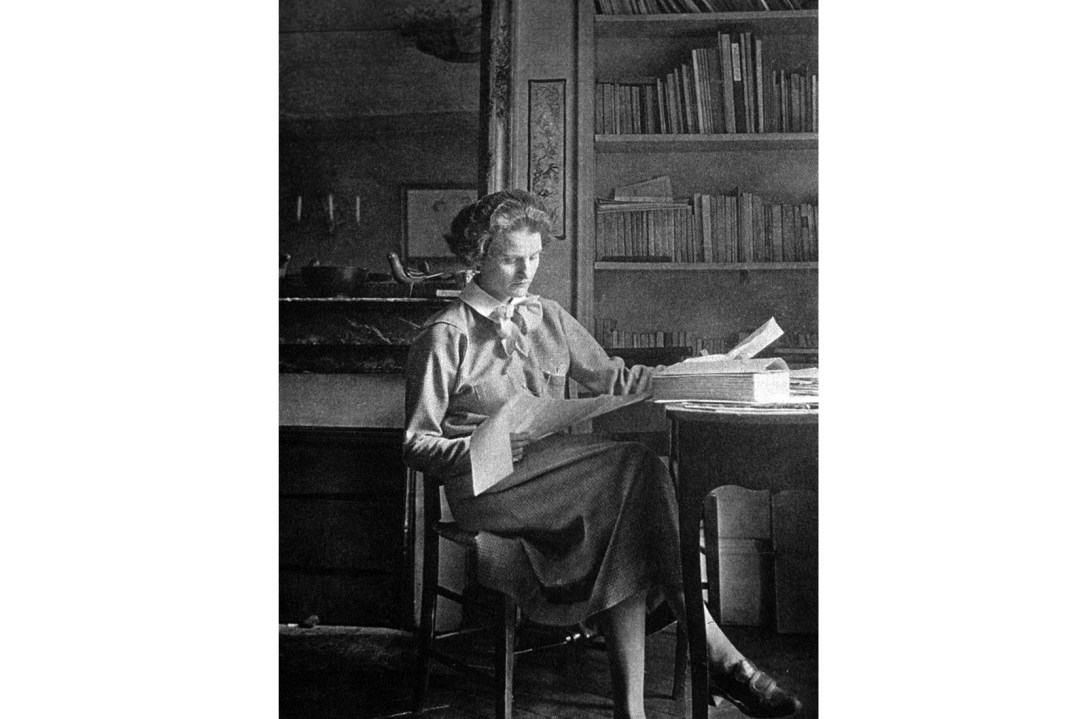

Gertrude Stein is at the other end of things; there was no marriage so utterly faithful and based in total mutual devotion as Gertrude’s with Alice B. Toklas. Souhami has already written a wonderfully entertaining joint biography of the two, but her new book places Stein in a more specific context than before. She had enough money to write as she chose, and the results were extraordinarily challenging. Oddly, I find her more readable as time goes on; even The Making of Americans now seems monumental but not impenetrable, and modern in places where Ulysses has an encyclopaedic, even Victorian air. She really was doing something new.

The figure who emerges with considerable credit is Bryher. She has been rather forgotten, apart from her connection with H.D., but she was evidently a clear-sighted and very intelligent woman. A small example: when she bought the magazine Life and Letters in 1935, she stockpiled so much paper in anticipation of the coming war that it could continue publication throughout the shortages.

A larger example might be her absolute clarity — in an article as early as 1933, called ‘What Shall You Do in the War?’ — that the Nazi attempt ‘to exterminate a whole section of the population’ would need to be confronted. ‘I cannot understand how any person anywhere who professed to the slightest belief in ethics could stand aside at such a moment.’

Not every member of a troubled minority has sympathy for the members of another, but Bryher had the sort of vision that often goes with impatience with the expectations of others. She turned up at the London opening of Show Boat at her parents’ demands, entering the Royal Box in a floral chiffon dress with

what was meant to be a draped cape behind hung down in front as if to conceal pregnancy. Bryher was wearing the dress inside out and back to front. ‘How is one to know?’, she asked.

Souhami is one of our most rewarding and inventive biographers, and this book is a splendidly hectic and vivid read. She has a novelist’s gift for the deft evocation. Beach’s appearance was ‘sprightly but unremarkable. She was five foot two, thin, with a brisk walk, determined chin, bobbed hair and brown eyes behind steel rimmed glasses.’ Neither Gertrude nor Alice ‘ever wore trousers… on one occasion Gertrude was mistaken for a bishop’. And she is often funny. When quoting a terrible poem by a Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven (‘So noble soul so weak a body/Thine body is the prey of mice’) Souhami just says: ‘It went on like that.’

There is a justifiable crusading element here, and there is no doubt that literary history has gone to some lengths to erase the presence, and nature, of lesbians. Souhami quotes with some scorn the absurdly misleading 1983 New York Times obituary of Bryher. Nowadays, these women are likely to be referred to under the euphemistic heading of ‘gender nonconformists’, when they were often absolutely clear about who and what they were. If No Modernism Without Lesbians goes some way towards making us understand how they thought of themselves, and what they did, it will have done some good.

Comments