Male killer whales are all mummy’s boys. That’s not a revelation; their curious and intense social lives have been studied for decades, but the extent to which a male orca depends on his mother has been revealed by new research, which shows that mothers routinely sacrifice their food and their energies for their enormous male offspring, compromising their own health and their ability to produce more young.

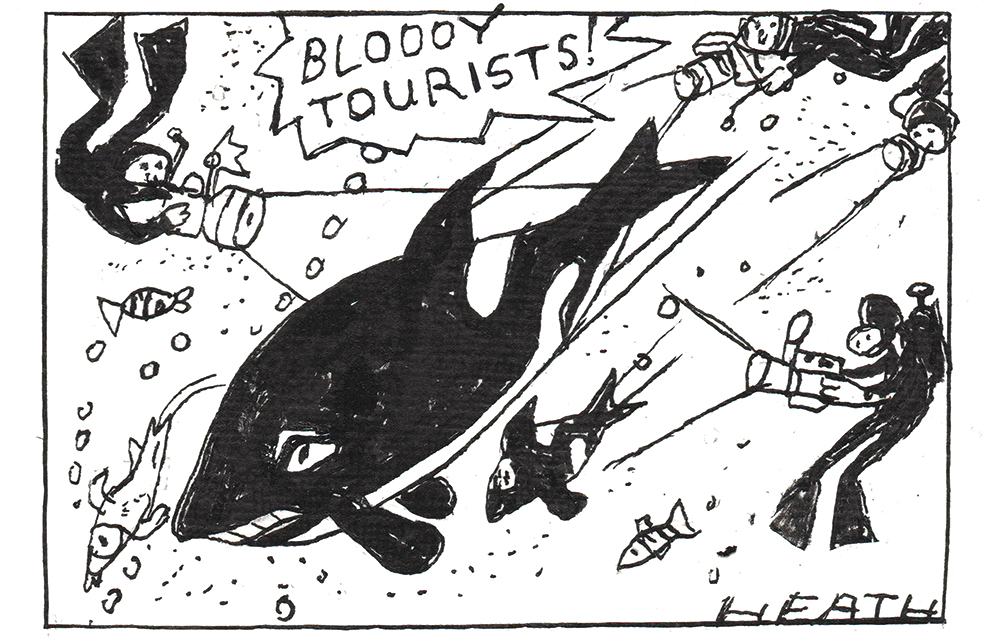

Orcas or killer whales – the former name is used more often these days – are not whales but big dolphins, up to eight metres long. They’re fierce enough under any name, but curiously selective in their ferocity. And that’s all about culture.

Not ours: theirs. The cultural life of orcas is a subject of scientific debate, and its implications are extensive. The idea that only humans have culture – that culture defines the separation of humanity from everything else that lives – is long exploded and orcas have helped greatly with the exploding.

The orcas of the Northwest Pacific are divided into three distinct populations, and the differences between them are not physiological but cultural. The differences show in how and what they hunt. There are the offshores, who specialise in deep-sea fish; there are the residents, who prefer salmon; and there are the transients, who specialise in marine mammals – seals and whales, up to and including the blue whale.

These different populations are called ecotypes and they don’t mix. (There are perhaps five different ecotypes in the Antarctic.) All orcas have the equipment to feed on each other’s preferred food, but they don’t even try. They stick to their own tastes and their own kind. They are very picky about it – captive animals of one ecotype refuse unfamiliar food to the point of starvation.

They are also xenophobic. They live in very tight matrilinear groups and, most unusually, all the young stay with the maternal group for the rest of their lives. Females become relatively independent of their mothers and meet their own feeding needs, but males don’t. Individuals leave the group for short periods to mate outside their group.

Orcas are deeply loyal to others of the same group and they go to considerable lengths to avoid groups of a different ecotype. Each group upholds both its separateness and its identity with its own range of distinct sounds. This sense of community and shared purpose helps them to operate as brilliantly effective co-operative hunters.

Orcas are gaudy animals. Sharks are just as fast and just as well armed, and they are coloured in ways that keep them relatively hidden even in open water, but orcas, with their dramatic black and white patterns, stand out at distance. It’s been speculated that it’s like football: they gain more from being able to keep tabs on their colleagues – team-mates – than they would from being hidden.

This is a species that makes us ask troubling questions, not about orcas but about humanity. The self-sacrificing mother is one such question; their cultural life is another and bigger one. Orcas are more remarkable than people ever thought when writing them off as mere killers: but why should we be surprised? All we have to do is read Darwin: ‘The difference in mind between man and the higher animals, great as it is, certainly is one of degree and not of kind.’

Comments