Last Saturday, a 41-year-old woman was arrested for what police described as ‘loitering between platforms’ at Newcastle Central station. By Monday, she had been successfully prosecuted – finding herself with a criminal conviction for breaching the newly enacted Coronavirus Act 2020. Days later, the conviction was dropped after police accepted they had misunderstood the law.

Why does all this matter? Well, clearly it’s important when law enforcement misuses some of the most draconian legislation passed in living memory. But the case tells us something else about the state of our criminal justice system. British justice, like the other parts of our constitution, is designed precisely so that failures like this do not occur.

The facts of the case are disturbing. Marie Dinou was stopped by British Transport Police and questioned over the reason for her travel. When Ms Dinou failed to give officers a satisfactory answer, she was arrested and taken in for questioning. Dinou was then held in custody for two nights before she was placed in front of district judge Sarah-Jane Griffiths at Tyneside magistrates’ court.

Throughout that time – between her first contact with officers and finding herself in the dock – Dinou communicated only once. She wrote on a piece of paper the single word ‘Aberdeen’.

47 per cent of appeals against a magistrates’ court conviction are successful

Due to her lack of communication, the defendant was unable to appoint her own legal representative or instruct a duty solicitor. When she continued her silence, judge Griffiths said that Dinou was being ‘obstructive’ before sending her back down to the cells. According to reports, no further attempt was made to determine the reason behind Dinou’s silence, whether it was kind of language barrier or medical issue – or whether she was indeed being ‘obstructive’. The judge ruled that the single written word, ‘Aberdeen’, was evidence enough of her fitness for trial.

In her absence, and without any legal representation, Dinou was found guilty under schedule 21 of the Act and was fined £660.

Following an investigation by the Times newspaper, it was established that Dinou had been incorrectly charged. The offence for which she was found guilty gives the police specific, limited powers: under schedule 21, officers can compel someone to undergo medical screening or self-isolation if they are suspected of having coronavirus. Failure to comply is a criminal offence. British Transport Police confirmed to the newspaper that they did not suspect Dinou of having the disease.

By Wednesday, the police had apologised, admitting that both they and the Crown Prosecution Service had failed in applying the law. The following day, the case was relisted and Dinou’s conviction was dropped.

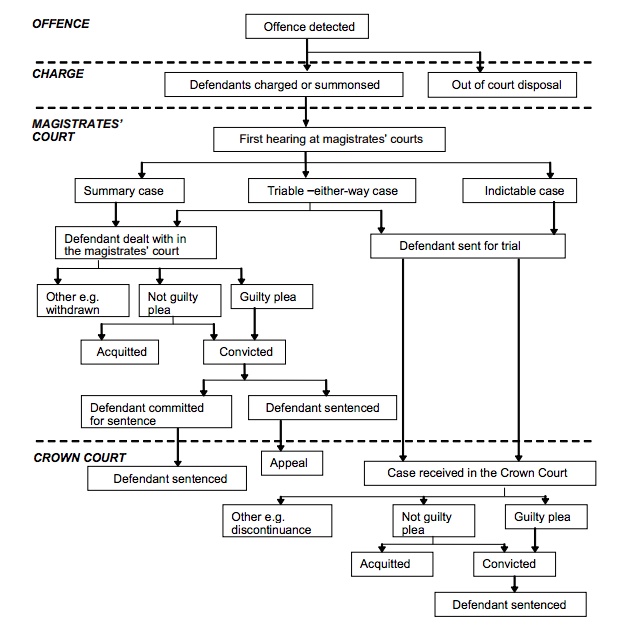

Apologising on behalf of the BTP, deputy chief constable Adrian Hanstock said: ‘It is highly unusual that a case can pass through a number of controls in the criminal justice process and fail in this way’. But is it really ‘highly unusual’ for this kind of failure to occur?

According to the most recent data from the Ministry of Justice, 47 per cent of appeals against a magistrates’ court conviction are successful. Interestingly, the campaigning group Transform Justice has found that those who represent themselves during these appeals are as successful as those who are represented by lawyers. This suggests that when a case comes before the crown court, the lower court’s ruling is so easily found to be wrong that the judge does not require the help of a professional legal mind to guide their decision.

In all of this, it is worth remembering that the police are not lawyers with batons. They cannot be expected to read and understand all 359 pages of a rapidly enacted piece of legislation. They instead use documents such as the College of Policing guidelines (which have since been updated in light of the Dinou case) to interpret the law so that a local bobby or PCSO can easily understand it. But that is precisely why the CPS – with its myriad of legal professionals – is separate from the police. They are the ones who assess the evidence and decide whether a case should proceed to court. The system is designed to limit power.

Once in court, the prosecution’s case should be rigorously tested. But this central judicial duty has become increasingly difficult after a decade of underfunding. Since 2010, the MoJ’s budget, which funds the court service, has been cut by around 40 per cent. Meanwhile, CPS budgets have been reduced by 30 per cent. Speak to anyone in the criminal justice system and they’ll tell you just how strained it has become. Lack of funding means that barristers and solicitors are paid little to research their case and hone their arguments. Judges face an ever-increasing flow of cases as courtrooms are closed to reduce staffing and upkeep costs. These cuts are crushing the very institution of which we should be so proud of in this country – our tradition of law and justice.

There is often an immediate, sometimes visceral reaction to discussions of this kind: why should I care about how criminals are treated? And to some extent that response is understandable. But ask yourself, in what state would you expect to find the British justice system, should you – a law abiding citizen – find yourself accused of ‘loitering’ on a train station platform? Through her silence, Marie Dinou provides a resounding answer to that question.

Comments