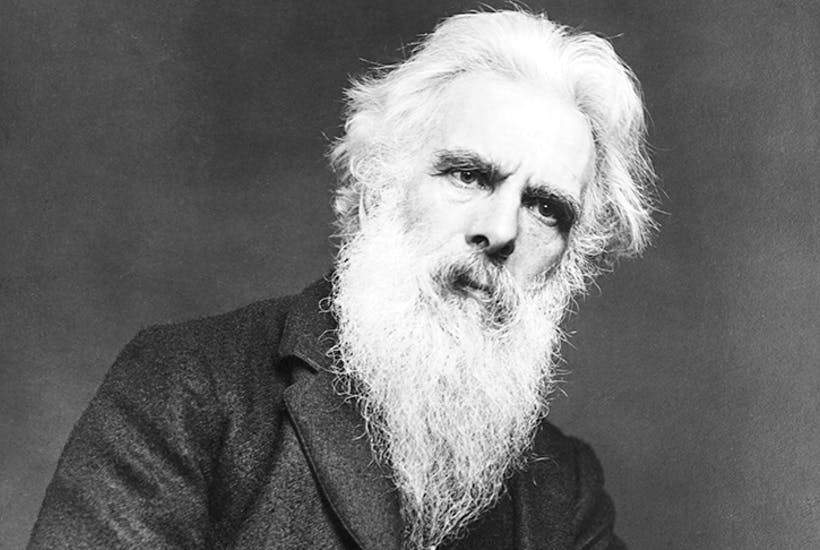

A distinctive pattern of horizontal and vertical lines appears in the background of many of Eadweard Muybridge’s best-known photographs, giving his images of animal and human locomotion a strangely modern appearance, despite their being products of the 1880s. The lines also anticipate those adopted in the 20th century against which US criminals appear in police identification parades — which seems appropriate, given that a decade prior to taking these images, Muybridge himself was convicted of murder. Had the small-town jury not delivered a verdict of justifiable homicide — despite the fact that Muybridge deliberately sought out and gunned down his unarmed victim, and showed no remorse thereafter — then these images would never have existed.

He embarked on his quest to freeze-frame motion after accepting a challenge to prove that horses lifted all four feet off the ground when galloping, but a different sentence at his trial would have left him with both of his own feet in the air, courtesy of the public hangman.

Muybridge’s victim, the glamorous chancer Harry Larkyns, sounds like a character from a cheap bodice-ripper

The story of Eadweard Muybridge — or Edward Muggeridge, as he was originally known before adopting the archaic Old English spelling of his first name — has been explored at length in a fair number of biographies over the past 50 years.

This volume, however, shines the spotlight equally upon the chequered and much-travelled life of the photographer’s hitherto largely unknown victim, Major Harry Larkyns, previously relegated to a shadowy walk-on part in books about the photographer, as if his sole purpose had been to provide a convenient corpse. In fact, as Rebecca Gowers points out in her introduction: ‘Harry lived an extraordinary life, filled with radical changes of circumstance, including three or four stints behind bars, wild romances and knife-edge adventures.’

Historians can be forgiven for having until now concentrated on the world-famous photographic pioneer rather than an itinerant chancer such as Larkyns, teller of tall tales, whose claims to have lived a glamorous, often dangerous, life in Europe and India might simply have been the bar-room inventions of a gifted raconteur. Unlikely boasts, certainly, but in many cases true, as Gowers ably demonstrates. She also had a personal reason for delving into the victim’s story, since she is a descendant of Harry’s sister Alice.

The son of an officer in the British Army in India, Larkyns was born in 1843. Brought to London five months later and left in the care of relatives, he was effectively abandoned by his parents, who returned to India without him and were killed in the Cawnpore massacre of 1857. As Gowers’s research shows, Harry himself later served in India, fought in the Franco-Prussian War, romanced opera singers in Paris, worked for the San Francisco Post and saw the California gold rush of the Comstock Lode at first hand. His life at times reads like fiction, and indeed, one anonymous eyewitness report of him in his latter days was so gushing that he sounds like a character from a cheap bodice-ripper:

Larkyns was over six feet tall, straight as a lance, and had a gift of spreading a ripple of sunshine wherever he went. His wit and clever stories, and general affability won him a legion of friends… He had been everywhere and seen everything… No one can mention anything that he could not do better than anybody else.

The heart of this book is a classic love triangle between Harry, Muybridge and Muybridge’s wife Flora. Given that Eadweard spent his life making images, and Flora worked as a picture-retouching artist for him and also for other photographers, it is odd then that despite the many illustrations which are reproduced in this volume and woven into the narrative, there is not a single portrait shown of her or Harry. Perhaps none survive, but it would have been nice if the question had been addressed. Speaking of photographs, the dust jacket features a series of images of a man taken from Muybridge’s 1887 leapfrog sequence with a blood-spattered bullet hole superimposed. An eye-catching design, particularly for anyone owning a copy of Jennifer Warner’s 2015 Muybridge biography, Murder in Motion, whose cover shows a series of images from the photographer’s 1878 galloping horse sequence, with a blood-spattered bullet hole superimposed.

Quite how Larkyns (who grew up variously in London and the west country) and Muybridge (from Kingston upon Thames)found themselves in a California mining town looking down either end of a pistol is a convoluted tale, and the author tells it well. Yet despite all the references to his supposedly irresistible charm and wit, Larkyns remains an elusive and often annoying figure, seemingly unable to stop himself from snatching defeat from the jaws of victory at every turn. It is hard not to lose patience when reading about him being bailed out from yet another unnecessary financial debacle, only to reappear in a new location to start the process over again. Full marks, though, to Rebecca Gowers for bringing this contradictory and little-known figure properly under the lens.

Comments