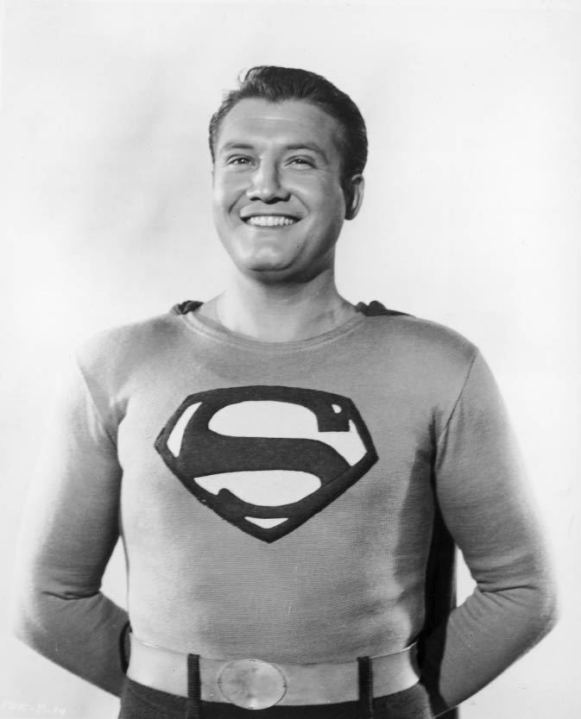

Peter Hoskin marks the 50th anniversary of the death of George Reeves, TV’s original Superman

Uncork the champagne, put on your best frock, and grin like the good times are never going to end. After all, it’s 1959, and Hollywood is the place to be. Billy Wilder’s Some Like It Hot has just left movie theaters; that great John Wayne film, Rio Bravo, is still doing the rounds; and the whole town — no, the whole world — is gearing up for the release of some Biblical epic they’re producing over at MGM. What’s it called? Oh, yes: Ben-Hur. So much glamour, money and talent that you can’t help but enjoy it all.

Or maybe not. Looking back from 2009 on that fertile patch of Hollywood history, there’s one moment which resonates dolorously above the clink of so many cocktail glasses. On 16 June 1959, only a few kilometres away from the famous Hollywood sign, the 45-year-old George Reeves was found sprawled across the bed in his home; a bullet wound to his temple; and blood, brain and bone fragments sprayed across the sheets. The coroner’s report marked it down as a suicide. But, to almost everyone else, it was no less than the death of Superman.

You see, starting with the feature film Superman and the Mole-Men in 1951, and continuing with the television series The Adventures of Superman (1952–1958), Reeves had been the flesh-and-blood incarnation of the caped hero for nigh on eight years. The children of America would rush to catch his latest adventures; their noses pressed against the screen as Reeves burst through walls, chased hoodlums and tied prop guns into knots. Swell, just swell!

Watching those shows now, their visceral appeal is clear from the opening sequence. A gun spits, as the voiceover intones: ‘Faster than a speeding bullet!’ A train hurries towards camera: ‘More powerful than a locomotive!’ A towerblock dominates the frame: ‘Able to leap tall buildings in a single bound!’ And, suddenly, there’s Reeves as Superman — all padded shoulders, jutting chin and brilliantined hair — standing resolutely in front of the Star-Spangled Banner, ready to fight for ‘Truth, Justice and the American Way!’. Make no mistake: the Soviets just couldn’t compete.

Get past the opening, and you’re treated to some incredibly warm character-work from Reeves. Both his Superman and his Clark Kent radiate kindliness: a quality determined not just by the scripts — as in Superman and the Mole-Men, when Superman actually defends the title creatures from the vigilante hysteria of small-town America — but also by the easy charm Reeves brings to the role. Sure, he can duke it out with the most depraved villains in all Metropolis. But what really makes this Superman special are the knowing winks he directs towards camera, or the impromptu moral guidance he gives to other characters and — by extension — the audience. In short, he’s a father figure. A Superdad for kids growing up in the shadow of The Bomb.

But now Superman, Reeves, father to millions, was dead. And the horrible news, coupled with the blunt headlines — ‘TV’S “SUPERMAN” KILLS SELF’ announced the frontpage of the New York Post — shocked many of his young fans to tears. They sat morosely in their rooms; lost their appetites; and refused to go to school. And who could blame them? For most, it will have been their first lesson in mortality, and among the most powerful they’d ever receive. Because if Superman can die, then you can be utterly certain that those around you — your family and friends — will too.

What dark effects does this kind of mass sorrow have? One of the more morbid statistics of the 20th century was that US suicide rates rose by 12 per cent in the wake of Marilyn Monroe’s barbiturate overdose. And while I’m unaware of any corresponding figure in the case of Reeves, it’s not inconceivable that his death marked a generation in ways that psychologists and sociologists cannot begin to comprehend.

If the effects of Reeves’s death are mysterious, then so too is the cause. For starters, just why did Reeves kill himself? There wasn’t any suicide note, so no one has ever known for sure. The prevailing theory is that he was depressed at his failure to land roles other than Superman; that he felt typecast, and doomed to play the Man of Steel until his hair fell out and his limbs gave way. After all, one of his earliest screen appearances had been in the biggest film of them all: Gone with the Wind (1939), as Scarlett O’Hara’s pre-Rhett beau, Stuart Tarleton. The future promised everything. But now he was reduced to the relative indignity of tearing around in tights, on cheap-looking sets, and all for an audience composed mainly of children. Would Brando or Dean lower themselves to this?

And yet. Many of Reeves’s colleagues reported how, beyond the occasional gripe, he seemed delighted that a seventh series of the Superman show was going into production only months later. The star would be well paid, and he’d get another opportunity to direct a few episodes, as he had done the year before. Yeah, on second thoughts, he had plenty of reason to be happy with his lot. He may not have been a Brando or a Dean, but Reeves had achieved a level of national fame and adulation that most actors would sell their grandmothers for.

These inconsistencies, plus a few more at the scene of Reeves’s death, have fuelled suspicions of foul play. Speculation about his affair with Toni Mannix — wife of Eddie Mannix, an MGM executive rumoured to have underworld connections — and his relationship with the professional party girl Leonore Lemmon is as nectar for a thousand internet crackpots. It inspired, too, the 2006 film Hollywoodland: an effective slice of neo-noir, featuring Ben Affleck as Reeves, whose conclusion is suitably ambiguous. In the end, I guess we’ll never know the full story behind Reeves’s sad death, 50 years ago this month. But the most likely explanation is the official one: a jaded actor put a gun to his head and pulled the trigger.

And so George Reeves took his place in a line which also includes James Dean, Marilyn Monroe, Jayne Mansfield, River Phoenix, Heath Ledger and too many more: talents who lived, acted and died prematurely in the public gaze, in good ol’ Tinseltown. More will follow them, because that is the nature of this particular beast. It gives players the greatest stage on Earth, only to stop them, brutally, mid-speech. And some perverse part of the Collective Mind will urge it ever on. Death is, after all, the ultimate way to smash the fourth wall between audience and screen performer; a reminder that, behind the costumes, make-up, cameras and special effects, they’re all of them — even Superman — as human as anyone else. Only more so.

Comments