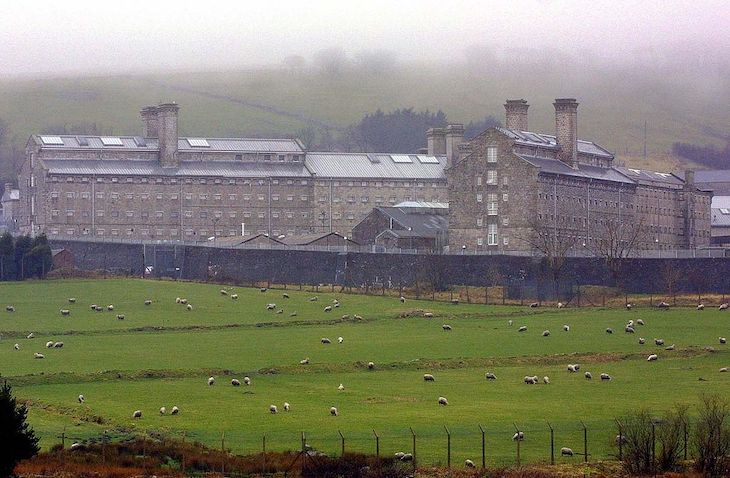

Taking my son for a walk yesterday, we passed HMP Dartmoor, where I served as a prison governor. Unknown to us, a dramatic and serious incident was unfolding just behind its austere walls. A prisoner had taken an officer hostage in the establishment’s segregation unit. I understand that the officer was overpowered while letting the perpetrator out into the unit’s exercise yard. I’m told that this prisoner was armed with a bladed weapon and that the officer was overpowered with his own handcuffs.

We won’t know whether all these details are accurate from the Ministry of Justice because they were only forced to reveal the scantest of details after the event was broadcast on social media. I’m told the incident was being followed by prisoners in possession of illicit mobile phones within the prison, adding another grim dimension to this ordeal.

As a former hostage negotiator trainer in the Prison Service, I am well acquainted with the dynamics of such incidents. The statistics on prison hostage taking show that these incidents are in decline. Many of the recorded ‘hostages’ are prisoners who are actually colluding with their ‘perpetrators’ for reasons that include boredom, excitement, manipulation and very occasionally are authentic, resulting in serious injury or death.

Offenders who want to take hostages have all day, every day to observe patterns and weaknesses

Taking a prison officer hostage is therefore relatively rare and obviously extremely serious. Officers carry PPE (personal protective equipment) such as batons, cuffs and Pava irritant spray. All these necessary tools can potentially be used against them. But they also carry keys – and that potentially gives a perpetrator ‘on the move’ access all the way to the front gate.

Hostage doctrine is built around isolating the incident and negotiating to a peaceful surrender without concessions. It’s likely that this officer was left on his own as the unit was evacuated of staff and the prison went into command mode. A hostage negotiator ‘Bronze’ will have been sent to the scene to establish communication with the perpetrator. One can only imagine how lonely and terrified the captive officer was during this period which I’m told lasted about three hours. It is a testimony to the skill and training of negotiators that the event was brought to a peaceful conclusion. I understand national tactical resources were also deployed, underlining just how serious this incident was.

The events of yesterday will be subject to an internal investigation. I have long argued that these investigations should be made public to the extent security allows to demonstrate that the service is assertively interrogating the incident and learning from it. It is probable that the whole prison regime was shut down yesterday. This sort of disruption in jails already woefully understaffed can easily create knock-on incidents as frustrated prisoners are held behind their doors for longer. There are several features of yesterday’s event that cause particular concern.

The segregation unit – however fluffily it is rebadged – is essentially the prison’s punishment block where some of the most dangerous and unpredictable prisoners are held. It will also hold prisoners who are segregated for their own protection. It isn’t clear which category the perpetrator fell into, or whether he straddled both. For these reasons alone, it ought to be the most secure and consistently staffed unit in the prison. From what I have gathered, the poor officer who was overpowered was alone with one colleague available elsewhere while unlocking the prisoner who took him captive. This and the fact a weapon was involved ought to be a ‘never event’ in any prison. The Lord Chancellor and political head of HM Prison Service Alex Chalk must ensure that there is a forensic and thorough examination of what happened along with implementation of recommendations to stop it recurring.

In January 2020, an officer at High Security HMP Whitemoor came within seconds and millimetres of being taken hostage, I firmly believe to be murdered, by two jihadist-inspired prisoners. They were later convicted of attempted murder as terrorists. This was only prevented by the immediate and brave intervention of colleagues who fought perpetrators armed with improvised weapons wearing what turned out to be fake suicide belts.

Category C prisons like Dartmoor have far fewer staff resources and perhaps a higher level of complacency. But offenders who want to take hostages have all day, every day to observe patterns and weaknesses in the agents of the state who are the most available targets. Across the prison estate, these weaknesses, aggravated by endemic staff shortages and an acute crisis of morale, will be noticed. They will be exploited.

While it appears that the crisis was resolved peacefully at HMP Dartmoor yesterday, the injuries to those taken hostage are psychological as well as physical. I hope that the officer concerned and his family are given all the assistance and care he will need to weather what must have been a shocking and terrifying experience. The perpetrator must be brought to justice and, if convicted, given the severest possible sentence. We owe a duty of care to those men and women working behind high walls to ensure that their working conditions are safe. We are failing in that commitment to a shocking extent. While this is unlikely to have been ideologically inspired, terrorists in prisons know how devastating a successful hostage incident – meaning a dead officer – would be to the rule of law inside prison. We must resource all our establishments to ensure to the greatest extent possible that front line staff go to work and home again without the risk of this horrifying experience.

Comments