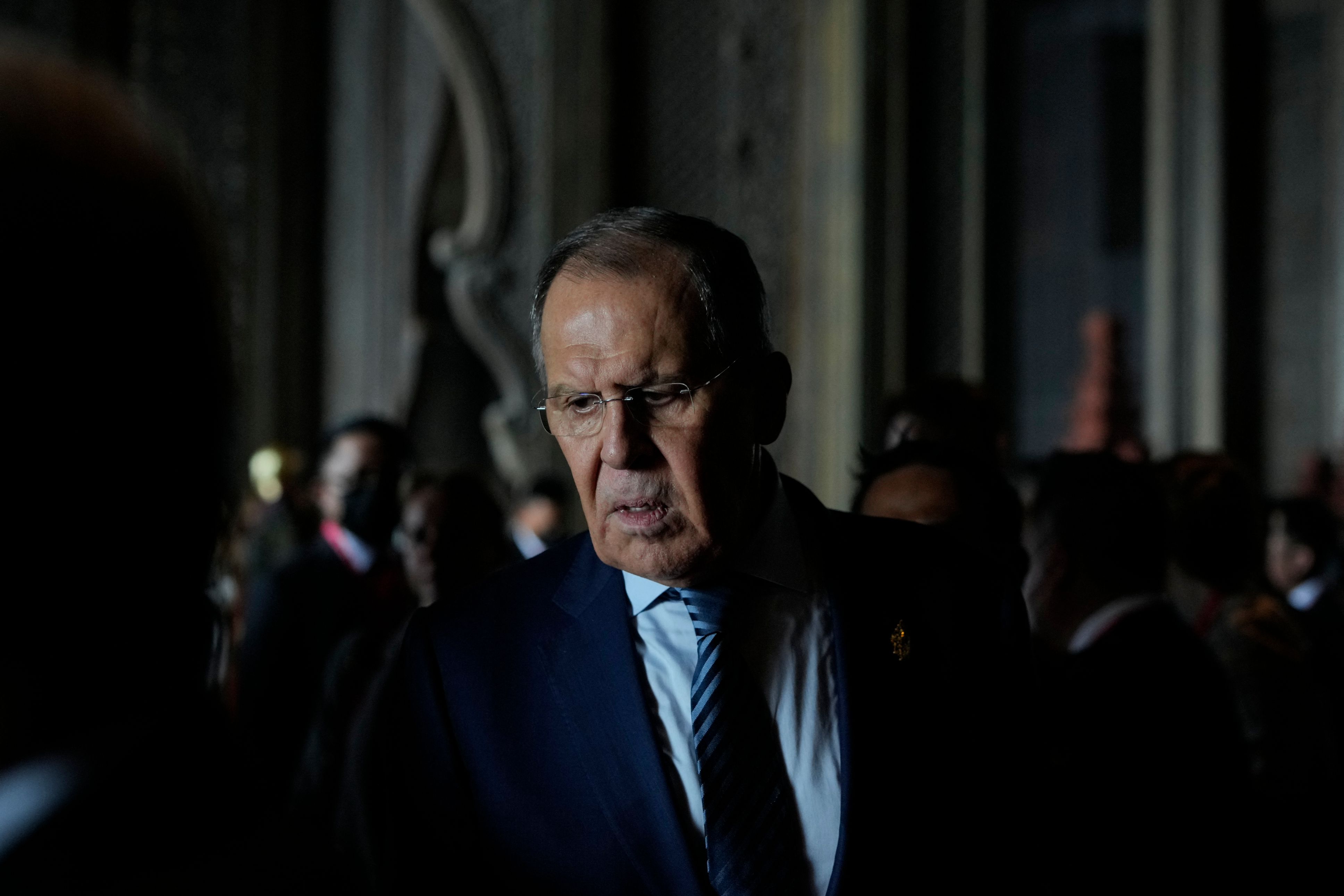

First came the claims that Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov was admitted to hospital in Bali on arriving for the G20 summit. No, we were then told by spokeswoman Maria Zakharova – it was ‘the ultimate fake’. Then local accounts emerged, saying that he popped in ‘for a check-up’. But does any of it matter?

On the face of it, it should. Vladimir Putin, true to form, havered as to whether to attend the summit, apparently deciding less than a week beforehand not to, both for security reasons but also because he knew that he would hardly get a warm welcome. The prospect of being publicly shunned and taken to task was enough to keep him home.

With Putin not willing to leave the comfort of his bunker, the task of representing Russia fell to Lavrov. This may sound like a logical step, but it underlines Moscow’s limited expectations for the summit. Lavrov, once a titan of global diplomacy, has been shrinking in authority and credibility since 2014, when he was forced to lie about the presence of Russian ‘little green men’ in Crimea. The role of a diplomat may indeed sometimes be to lie unblinkingly for their government. But to do so always has a price and since then, Lavrov has had to defend the indefensible and assert the implausible too often to retain even the last of his stature. It is also clear just how little authority he has in Moscow. He was not consulted before the 2014 seizure of Crimea, let alone Putin’s decision to invade in February. No wonder the 72-year-old has repeatedly petitioned for permission to retire: he is nothing but a glorified messenger and understandably grumpy propagandist.

Lavrov – who might regard any heart problems as a blessing in disguise if it finally means he can retire – is not who we should be watching

In this context, the story or non-story of his hospital trip demonstrates the automatic defensiveness and mendacity of the Russian foreign ministry these days – why could its press director, Maria Zakharova, not simply have admitted he had a brief check-up given that it was inevitable that it would leak? – but also the degree to which personalia had to replace policy. In practice, Moscow had nothing to offer in Bali except a token presence and a refusal to negotiate in any meaningful way. Tellingly, government newspaper Rossiiskaya Gazeta headlined its main report ‘Moscow’s opponents failed to turn the G20 summit into a platform for settling scores – Russia’s position was heard and taken into account’.

Then again Russia’s foreign ministry itself has been in decline for years. It still occupies an imposing tower overlooking Smolensk Square, one of the Stalin-Gothic ‘Seven Sisters’ dominating Moscow’s skyline, which remains a hive of activity. However, its denizens are increasingly and often bitterly aware of not just of their isolation in the world, but also their marginalisation in Moscow.

Authority over foreign policy matters, and even their execution, has shifted to new hubs as Putin’s new security state emerges. One is the defence ministry on Arbatskaya square, twenty minutes’ walk closer to the Kremlin. Another is the foreign intelligence service (SVR) HQ in Yasenevo, in southern Moscow. And most of all, the offices of the Security Council Secretariat behind their iron gates on Ipatevskii Alley, just behind Red Square.

While Lavrov was stonewalling and hand-shaking in Bali, for example, it was SVR director Sergei Naryshkin who was in Ankara meeting his US counterpart, CIA director William Burns, ostensibly to talk about ensuring that there would be no nuclear escalation in the war – there was a very clear message from the Americans that there would be no negotiations over Ukraine – but also to keep open channels of communication.

Meanwhile, security council secretary Nikolai Patrushev – a former head of the federal security service and now Putin’s de facto national security adviser – had just come back from Tehran, where he was not only negotiating further supplies of drones and missiles but hammering home Moscow’s message that ‘the world is going through a turning point’ and that ‘the so-called US hegemony is becoming a thing of the past. Russia and Iran today are at the forefront of the struggle for the establishment of a multipolar world order’.

Patrushev is also in regular touch with his US counterpart national security adviser Jake Sullivan, just as it was defence minister Sergei Shoigu who recently contacted his British, American, French and Turkish counterparts to discuss the situation in Ukraine. In short, Lavrov – who might regard any heart problems as a blessing in disguise if it finally means he can retire – is not who we should be watching anyway. We should be focused on the hard men in the security apparatus, whose hearts seem rather harder.

Comments