The tenth anniversary of the slaughter of Charlie Hebdo journalists reminds us that the literary establishment has long been equivocal when it comes to defending free speech. So news this week that the Royal Society of Literature is in ‘meltdown’, after singularly failing to defend its members when under attack, sadly comes as no surprise. Indeed, the departure of the once-great society’s chairman and director, shortly before a forthcoming annual general meeting that was expected to have seen calls for their resignation, should be welcomed by all who support artistic freedom.

The Royal Society of Literature has had a particularly turbulent few years

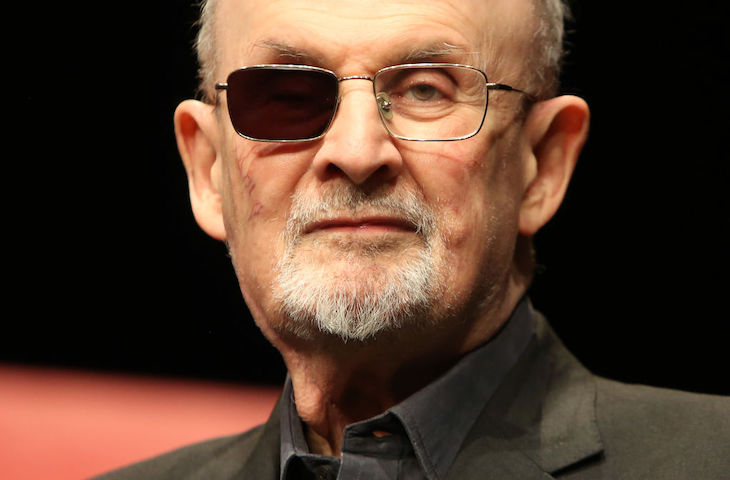

Globally, the rift among literature’s great and good became starkly apparent just weeks after the murder of twelve Charlie Hebdo journalists in 2015. PEN America, a literary organisation that defends free speech, honoured the satirical magazine with a freedom of expression award at its annual gala dinner. Immediately, six prominent writers, including Michael Ondaatje and Peter Carey announced their decision to boycott the event. After being slammed by former PEN president Salman Rushdie as ‘pussies’, other authors rushed to declare – not Je Suis Charlie – but that they, too, objected to dead journalists being rewarded for material that ‘violates the acceptable’.

In response, Rushdie told the New York Times, ‘If PEN as a free speech organisation can’t defend and celebrate people who have been murdered for drawing pictures, then frankly the organisation is not worth the name’. Indeed. But sadly, on this side of the Atlantic, in the years before the Free Speech Union, neither the Royal Society of Literature nor the Society of Authors rushed to support free expression. As a consequence, both have been riven with internal disputes ever since.

The Royal Society of Literature has had a particularly turbulent few years. Its leadership failed to properly support Salman Rushdie after a brutal attack in 2022 almost cost him his life and left him severely injured. And it failed to give its full support to Kate Clanchy after she was mobbed on social media and her award-winning book on her experiences as a teacher was withdrawn by her publisher. Back in December 2023 the society suspended publication of its own magazine, allegedly because one article ‘contained a passage sympathetic to Palestine’, although the society denies this was the reason. Members demanded an extraordinary general meeting so that ‘the serious issue of attempted censorship can be resolved’.

Authors need free expression to produce work that is creative, challenging, provocative and beautiful. In a censorious climate, when publishers are risk averse, sensitivity readers condemn all but the blandest sentiments and social media mobs root out heretics, authors need professional organisations to defend their intellectual freedom. But, as fellows of the Royal Society of Literature have now discovered, they have leaders who – like the PEN boycotters of 2015 – place ‘inclusion’ and ‘diversity’ above free speech.

Under the leadership of chairman Daljit Nagra and director Molly Rosenberg, the charity set up to ‘reward literary merit and excite literary talent’ badly lost direction. Most egregiously, the society failed to stand in solidarity with Rushdie after he was attacked. When past president Dame Marina Warner questioned this absence, she was reportedly told by the society’s management that to support Rushdie could cause ‘offence’. However the Royal Society’s president, Bernardine Evaristo, Nagra and Rosenberg may wish to spin this, not wanting to ‘offend’ those who support a brutal attack is grossly offensive to a man left fighting for his life. The Royal Society of Literature shamefully chose to protect the feelings of those who condemned Rushdie, even as the author lay in hospital.

Evaristo later explained that the organisation could not take ‘sides in writers’ controversies and issues but must remain impartial’. But such glib words, following a near fatal attack, suggest astonishingly poor judgement and moral cowardice. Despite Evaristo’s protests to the contrary, the continued refusal to properly support Rushdie betrays her stubborn determination to bring politics into the heart of the Royal Society of Literature.

Once a bastion of literary excellence, the society introduced a series of changes designed to increase ‘inclusivity’. Most notably, in order to challenge the organisation’s image as ‘elitist’, the public now gets a say in choosing new members. Membership now seems to be based on meeting the society’s demand for diversity rather than having created work of literary excellence.

In a bid to be inclusive, the Royal Society for Literature has dropped its commitment to excellence and failed to defend the right of authors to express themselves freely. It is hardly surprising that, with the resignation of Nagra and Rosenberg, the 205-year-old society now faces collapse. Tragically, having reduced itself to just another morally-vacuous, woke institution, its demise cannot come soon enough.

Comments