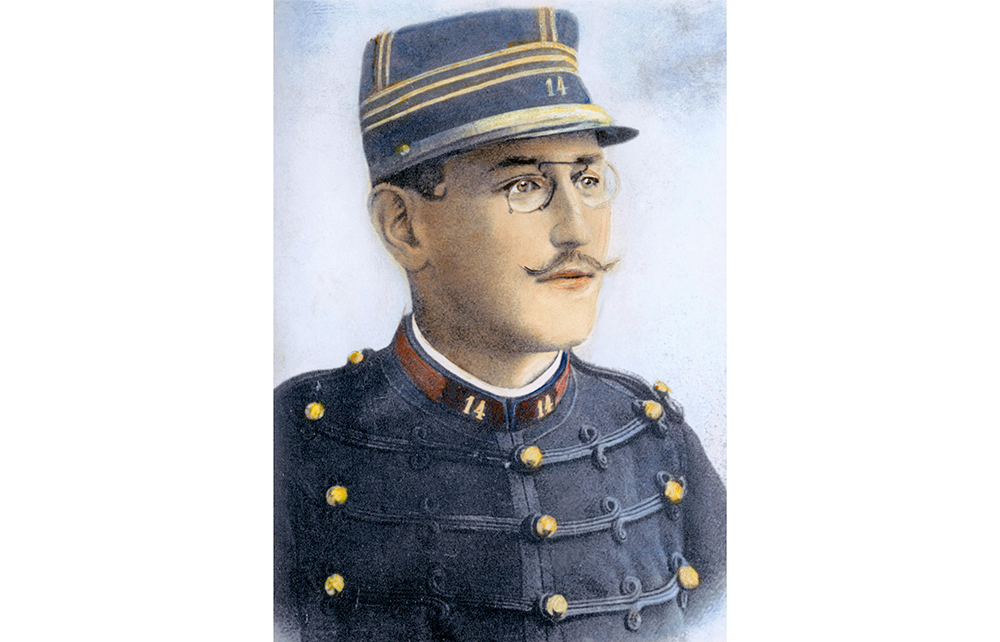

A short new book on Captain Alfred Dreyfus, the proudly patriotic French army officer who was falsely accused in 1894 of being a German spy, and whose court cases divided France into two warring camps, could not have been better timed. For the division sounds horribly familiar. Liberal, democratic, secular, cosmopolitan, urban France was pitted against provincial, religious, authoritarian, anti-immigrant, chauvinistic France.

Dreyfus, an assimilated Alsatian Jew, was first sentenced by a military court, using faked documents and trumped-up charges, to life imprisonment on Devil’s Island, off the coast of French Guiana. When it became obvious that it wasn’t Dreyfus who had handed military secrets to the Germans but Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy, a disreputable minor aristocrat addicted to gambling and women, a second trial was held. To cover up the fraudulence of the first trial, Esterhazy was acquitted, and Dreyfus remained, more dead than alive, shackled to his bed in his island prison.

A wave of anti-Semitic riots convulsed the whole of France. This frenzy was whipped up by fiercely anti-Semitic newspapers such as La Libre Parole, comparing Jews to rats who should be eliminated. But at the same time, supporters of Dreyfus, including the writer Émile Zola, organised themselves to defend the liberal republic. Zola published his famous article J’Accuse, in which he denounced the anti-Semitism of the French general staff as well as the odious press that called for the death of Jews, liberals and other enemies who were supposedly polluting the purity of France. Zola, and many liberal intellectuals, were the Dreyfusards. Their opponents were the anti-Dreyfusards.

In the end, the case against Dreyfus collapsed and he was pardoned. Esterhazy fled to a village in Hertfordshire, where he died in 1923. Dreyfus died in 1935. He was lucky not to have lived a few years longer, for then he would have seen the revival of the anti-Dreyfusards in the Vichy regime, which assisted the Germans in deporting more than 75,000 Jews to the death camps. His favourite granddaughter, Madeleine Lévy, was murdered in Auschwitz.

Maurice Samuels tells the story of the Dreyfus affair well. If he is to be faulted at all it is that he bangs home the idea that anti-Semitism was at the core of the whole sordid business with a little too much fervour, as though many people would doubt it. He also has it in for Hannah Arendt, and the Canadian Holocaust historian Michael Marrus, who, in his view, pay insufficient attention to the support of French Jews for Dreyfus.

Anti-Semitism obviously played a major role. When an intelligence leak was discovered, it seemed almost natural to many senior French officers that the only Jew assigned to the general staff should be the main suspect. Not only was Dreyfus Jewish, he spoke perfect German, as did anyone from the Alsace, which was claimed by Germany after the defeat of France in the Franco-Prussian War. To his opponents, Dreyfus, who had always worn his patriotism on his sleeve, as it were, was not a true Frenchman.

But French anti-Semitism was complicated. There were socialist anti-Semites who blamed the Jews for capitalism – echoes of which can also be heard today. On the reactionary right, which had never made its peace with the French Revolution and yearned to return to an imaginary ancien régime ruled by king and church, Jews stood for everything they hated about the liberal republic.

Dreyfus was considered the perfect enemy within – the treacherous Jew whose loyalty could never be trusted

This hatred was given a boost by the humiliating defeat of France in the war with Prussia. France’s shame led to a collapse in national self-confidence. The father of the modern Olympic Games, Baron de Coubertin, for example, hoped that a dedication to organised sports would help restore the country’s virility by ‘rebronzing’ the French, as he put it. Thomas Arnold was his hero. More sinister forces thirsted for revenge against enemies without and within.

Dreyfus was the perfect enemy within – the treacherous Jew, whose loyalty could never be trusted. But the curious thing about modern French history is that Jews were also more emancipated and successful in France than in any other European country. Jews played a major role in finance, politics, journalism, the arts and even the armed forces. Their very success in the modern democratic state provoked the reaction against them, from the old aristocracy who felt their grip on society slipping to the professional classes who resented Jewish competition.

The near-total assimilation of secular Jews also explains why many were reluctant to join the Dreyfusards. Samuels quotes something Léon Blum, the future socialist prime minister, said about the affair: ‘A great misfortune had befallen Israel. We suffered it without saying a word, hoping for time and silence to wipe away its effects.’

The Dreyfus affair, then, put the French republic to a huge test. And despite the anti-Semitic wave that swept the country, the republic withstood it. Only the German invasion of 1940 put a temporary end to France’s relatively open society by allowing the most anti-democratic figures to form a collaborationist government.

Samuels is interesting on some of the consequences of the affair. For one thing, it was a spur to Zionism. He also observes that the Dreyfusard/anti-Dreyfusard conflict is far from over. He mentions the extreme right in France today, where the likes of Éric Zemmour (an Algeria-born Jew, no less) are not only reviving old reactionary ideas but casting doubt on the innocence of Dreyfus.

But it is perhaps a little harsh to mention only France in this context. A far more dangerous exponent of the anti-immigrant, authoritarian, chauvinistic right could be the next president of the United States – and he has probably never even heard of Captain Alfred Dreyfus.

Comments