The world came closer to thermonuclear warfare during the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962 than ever before or since. Most Americans now aged between their late fifties and late sixties remember ‘duck and cover’ drills during the crisis which taught them to hide under school desks and adopt the brace position in case of nuclear attack. One man who at the time was a 13-year-old schoolboy in Buffalo, New York, told me how on the day after a drill, ‘I was sitting on the big yellow school bus thinking: Will I get home today? Am I going to die? Is this it? Just looking out the window at the world passing by and wondering…’.

Because there were no organised drills in British schools, recollections on this side of the Atlantic of those who were schoolchildren during the crisis are more various. Some, particularly at primary schools, were kept in ignorance by parents and teachers and now have no memory of the crisis. But I’ve been struck by the fact that even some very young British schoolchildren shared the fears of the 13-year-old in Buffalo. The mother of a former student of mine who was six at the time recalls hearing her father, a naval officer who was on leave during the crisis, discussing the threat of nuclear attack with her mother. Though the six-year-old’s parents spoke in a way their daughter was not supposed to understand, their peculiar conversation only succeeded in attracting the little girl’s horrified attention. She stood up in class next day and announced to the other children: ‘You are all going to die.’ The school was sympathetic but telephoned the little girl’s mother (who still remembers the telephone call) to take her home for the rest of the day.

The six-year-old English girl, like the 13-year-old boy in Buffalo, was right to be worried. The Soviet leader, Nikita Khrushchev, had calculated that it would be possible to install missile bases in Cuba so secretly that the United States would not notice them until they became operational. Had Khrushchev’s plan succeeded, the United States might well have launched an air strike against the bases, accompanied by a land invasion of Cuba. When the first intelligence of the construction of the bases reached the White House on 16 October 1962, a majority of President John F. Kennedy’s chief advisers (collectively known as Excomm) were initially in favour of an airstrike. Only the fact that the bases were discovered before they were operational, leaving time for negotiation, led Excomm to change its mind.

The sequence of events which led to the discovery of the missile bases began with a flash of personal inspiration by the head of the CIA, John McCone, while he was on honeymoon at Cap Ferrat on the French Riviera less than a month before the crisis began. Though there had already been reports of Soviet missiles on Cuba, all the missiles identified had been surface-to-air defence missiles which could not be used to attack the United States. But the crucial question, which McCone asked himself and Washington during his honeymoon, was what the growing number of these missiles had been sent to Cuba to defend. Could it be offensive missile site construction? The urgency with which McCone asked that question (obvious in retrospect but not at the time) demonstrates the advantages of senior officials getting away from their office desks at moments of crisis. The therapeutic combination of a honeymoon and Cap Ferrat gave McCone an ideal opportunity for fresh thinking, unencumbered by bureaucratic routine.

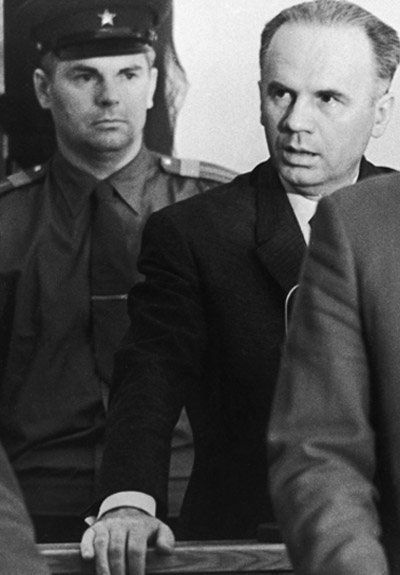

On the morning of Tuesday 16 October Excomm began studying the first of the photographs taken by U-2 spyplanes showing the construction of the missile sites. The ability of photo analysts and other experts to interpret the photographs was greatly enhanced by intelligence supplied by probably the most important western agent of the Cold War, Colonel Oleg Penkovsky, deputy head of Soviet military (GRU) foreign intelligence, who was run jointly by MI6 and CIA case officers. All the top-secret reports on the Cuban missile sites circulated to Excomm during the 13 days of the crisis carried the code word Ironbark, indicating that they made use of documents provided by Penkovsky.

Some of Penkovsky’s intelligence was handed over in London in April 1961 in Room 360 at the Mountjoy Hotel, Marble Arch, while he was travelling with an official Soviet delegation to Britain. After being secretly debriefed at night, he asked his MI6 and CIA case officers to photograph him dressed in the uniforms, successively, of a British army and US army colonel, as a symbol of where his true loyalties lay. The photographs still survive.

Receiving intelligence from Penkovsky in Moscow was made much more difficult by the tight KGB surveillance of western embassies and their intelligence stations. Probably the most ingenious method was devised by the deputy head of the CIA station, Hugh Montgomery. Many years later I was flattered to be asked by Hugh, then in semi-retirement, to sign a copy of my book on how US presidents have used intelligence. I asked him how I should dedicate it. He replied, ‘Write “To the Cistern Kid”.’ Hugh then told me how he had arranged for Penkovsky to be one of the Soviet officials invited to an Independence Day party at the US ambassador’s residence in Moscow, Spaso House. Penkovsky was told to visit the rest room and leave Minox camera cassettes containing photos of top-secret documents in a waterproof container inside the cistern (a form of ‘dead-letter box’ commonly employed by both sides in the Cold War).

Retrieving Penkovsky’s container proved more difficult than Hugh Montgomery had anticipated. He had expected the toilet to have the usual low-level US cistern. Instead, when he entered the rest room, he discovered that there was a cast-iron -Russian -cistern positioned above head height. When Hugh tried to stand on the wooden lavatory seat, it broke and he found himself with one foot inside the toilet. Next he stood on the washbasin. Just as he retrieved the container from the cistern, the washbasin came away from the wall. By now rather bedraggled, Hugh decided not to stay for the rest of the reception. He told me that, just as he was leaving, he heard another guest complain that someone had trashed the rest room. Tragically, Penkovsky was caught by the KGB on the eve of the crisis and later executed.

Crucial to the ability of Excomm, in October 1962, to arrive at a policy which made possible a peaceful solution to the crisis was that it had almost seven days to discuss in private both the latest intelligence and its policy options without a single leak by the US media. It is difficult to believe that there would be no leak during such a major crisis today. From the moment the media discovered that all President Obama’s leading advisers were simultaneously away from their desks (as they were in 1962), they would descend on the White House and demand to be briefed. Obama’s press secretary, Jay Carney, would no doubt remind them of the precedent of the Cuban missile crisis and of how important it had been then for the President and his advisers to have an undisturbed week to work out how to seek a peaceful resolution. At least some of today’s media would leave the White House briefing convinced that if they did not leak the story, one of their rivals would.

We now know that the secret very nearly got out. Those from whom President Kennedy was most anxious to conceal the discovery of the missile sites were the hawks in Congress — the ‘War Party’, as he called them. The latest volume of Robert Caro’s monumental biography of Lyndon B. Johnson, then vice-president, reveals that he almost immediately leaked news of the discovery to the leader of the War Party, Senator Richard Russell, a man with a deserved reputation for what Caro calls ‘monumental racism’ as well as monumental loathing of the Soviet Union. Mercifully Russell did not tell his friends in the media. Had he done so, the consequences could well have been dire. Kennedy was probably right to believe that ‘any premature disclosure could precipitate a Soviet move or panic the American public’.

On the evening of Monday 22 October, the crisis became public for the first time during a presidential broadcast when Kennedy revealed the construction of the missile sites and announced a US naval ‘quarantine’ to prevent further Soviet shipments to them. At the end of the week Khrushchev suddenly brought the crisis to a dramatic end by agreeing to dismantle the bases. For most of that week, however, preparations for the possibility of Armageddon continued in both London and Washington. Had the crisis worsened, the Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan, would have authorised the move to a ‘Precautionary Stage’ in the countdown to war. Macmillan and the War Cabinet, together with senior defence and intelligence staff, would have taken up residence in a large top-secret underground bunker, codenamed successively Burlington and Turnstile, near Corsham in the Cotswolds, whose existence was first publicly revealed by Peter Hennessy.

Macmillan directed that Turnstile should ‘act as the seat of government’ in what he optimistically described as ‘the period of survival and reconstruction’ following a nuclear attack. More realistically, in a third world war, the bunker would probably have provided no more than a short-lived underground refuge for the remnants of British government while Britain was obliterated above them. A few years ago I visited Turnstile. What most surprised me was its sheer size: miles of underground tunnels with names such as North-West Ring Road. Transport was provided by electrically powered, mostly orange, trolleys. Some of the recharging stations positioned along the tunnels were still functioning. Much else in Turnstile was a mundane memorial to the British way of life 50 years ago. Only the Prime Minister had a private bathroom. The kitchens contained, as well as rows of tea urns and boxes of unused crockery, the biggest deep-fat fryers I have seen. I imagined the last meals in British history being largely composed of tea and chips.

While interviewing those with memories of the missile crisis, I’ve been struck by how similar most of their recollections are. One man, who was a sixth-former in Bristol in 1962, recalls: ‘We had all been only too aware of the possibility of Armageddon. But when the crisis was resolved we were much more relieved than ecstatic.’ That describes exactly my own student memories of the end of the most dangerous moment in British history.

Comments