It’s the most beautiful restaurant in London – and the oldest. Built in 1573, Middle Temple Hall is celebrating its 450th anniversary. It’s also where Shakespeare held the premiere of his Christmas play, Twelfth Night, in 1602. How strange that hardly anyone knows about the best Elizabethan hall in London. It’s mostly used by barristers but the public can eat there too, as long as you book ahead.

I looked up to high table to see a purple-faced bencher, glaring down at me

The food is lovely, substantial, marvellously unponcey fare and fantastically good value for such a staggering spot – on the western edge of the City, on the banks of the Thames. When I was there this month, I had cream of mushroom and tarragon soup (£4.50), followed by turkey breast with sage and onion stuffing (£12), and a glass of Middle Temple Bordeaux Blanc (£6). But you’re not really there for the food, so much as the staggering architecture.

The four Inns of Court – Middle Temple, Inner Temple, Lincoln’s Inn and Gray’s Inn – have a tremendous range of buildings, going back to the Temple Church, built by the Knights Templar in 1160, in imitation of Christ’s Sepulchre in Jerusalem. Lawyers have been practising in this corner of London for 700 years.

Middle Temple Hall is the best of all those buildings. Even though I had a hundred lunches there in my brief career as a barrister – and had to eat 12 dinners to qualify – I still never tire of staring up at the double hammerbeam roof, the best in London. (These days, aspiring barristers attend ten qualifying sessions, which combine dinner with lectures and debates).

I have had the odd low moment in the hall. One day, as I ate a solitary lunch, reading a paper, a worried waiter walked the length of the hall to say, in a kind way, ‘I’m so sorry, sir, but a bencher [a senior barrister] has asked me to remind you of the rule about not reading in hall.’ I looked up to high table to see a purple-faced bencher, glaring down at me. He, too, was eating on his own but preferred to stare into space rather than read – and insisted I did the same.

He and his fellow benchers sit beneath a mammoth equestrian portrait of Charles I, a Peter Lely copy of the famous Van Dyck picture. The high table they eat off was carved out of a single oak, floated down the Thames from Windsor on the orders of Elizabeth I.

Other barristers – and visitors, too – sit on long benches on a lower level, literally below the salt (the salt container, once so hallowed that it was reserved for richer diners higher up the food chain). One of the tables – ‘the cupboard’, where I entered my name in the Inn’s books when I was called to the Bar – was made from the hatch cover of the Golden Hinde, Sir Francis Drake’s ship, in which he circumnavigated the world.

Drake was a regular visitor to the Inn in the 16th century, when the four Inns of Court were described as the third university of England. Sir Walter Raleigh was a member of Middle Temple. Both his portrait and Drake’s are on show in the minstrels’ gallery looming over the hall.

In the gallery, there’s a tragic painting of when the hall was bombed in 1940. Its great treasure, the 1573 screen, was blasted into smithereens. Collected into 200 sacks, the smithereens were put back together like a vast jigsaw puzzle. There were only a few missing pieces, replaced by oak fragments from a 700-year-old barn.

The screen was built at that magic Elizabethan sweet spot – the crossover between medieval English architecture and the arrival of classical architecture. It was built over 30 years before Inigo Jones, fresh from his Italian travels, pulled off the first formally correct classical buildings in the country. And so the Middle Temple screen is a triumphant – if not quite architecturally right – mixture of Roman Doric columns, metopes, caryatids and Netherlandish strapwork. These spectacular details were carved by Protestant Huguenot refugees, under the auspices of the Middle Temple Treasurer, Edmund Plowden, a favourite of Elizabeth I.

The hall was celebrated almost immediately after it was built. Only five years later, in 1578, Elizabeth I herself came, in a surprise visit, to admire the new hall and listen to a barristers’ debate. It was historically accurate then that, in Shakespeare in Love (1998), Judi Dench, playing Elizabeth I, makes a visit to Middle Temple Hall – although she watches The Two Gentlemen of Verona, not Twelfth Night, in the film.

Shakespeare himself almost certainly came to the hall. And the premiere of Twelfth Night took place there on 2 February 1602 – Candlemas, celebrating the formal end of Christmastide. John Manningham, a law student, studying at Middle Temple, wrote about the show in his diary. The play would not be published for another 21 years, when the First Folio came out 400 years ago, in 1623.

There are plenty of ‘Inn’ jokes and references in Twelfth Night to confirm that Shakespeare wrote it for an audience of lawyers in Middle Temple. When Malvolio is imprisoned, he complains to the Clown that it’s as dark as Hell. The Clown replies, ‘Why, it hath bay windows transparent as barricadoes, and clerestories towards the south-north as lustrous as ebony.’

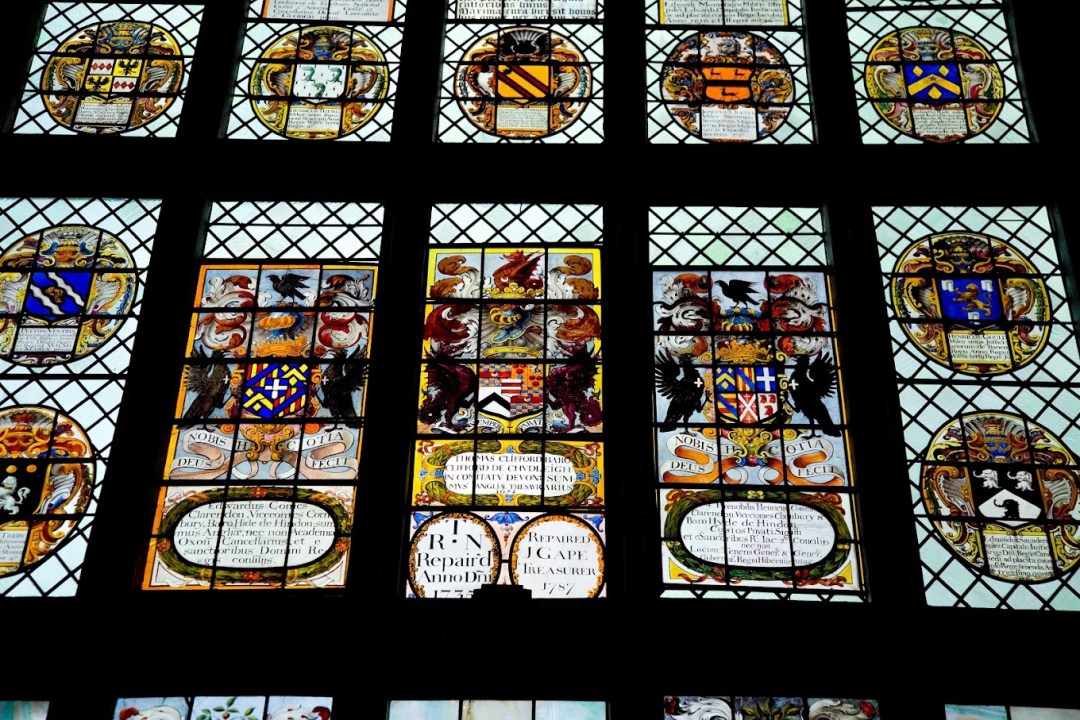

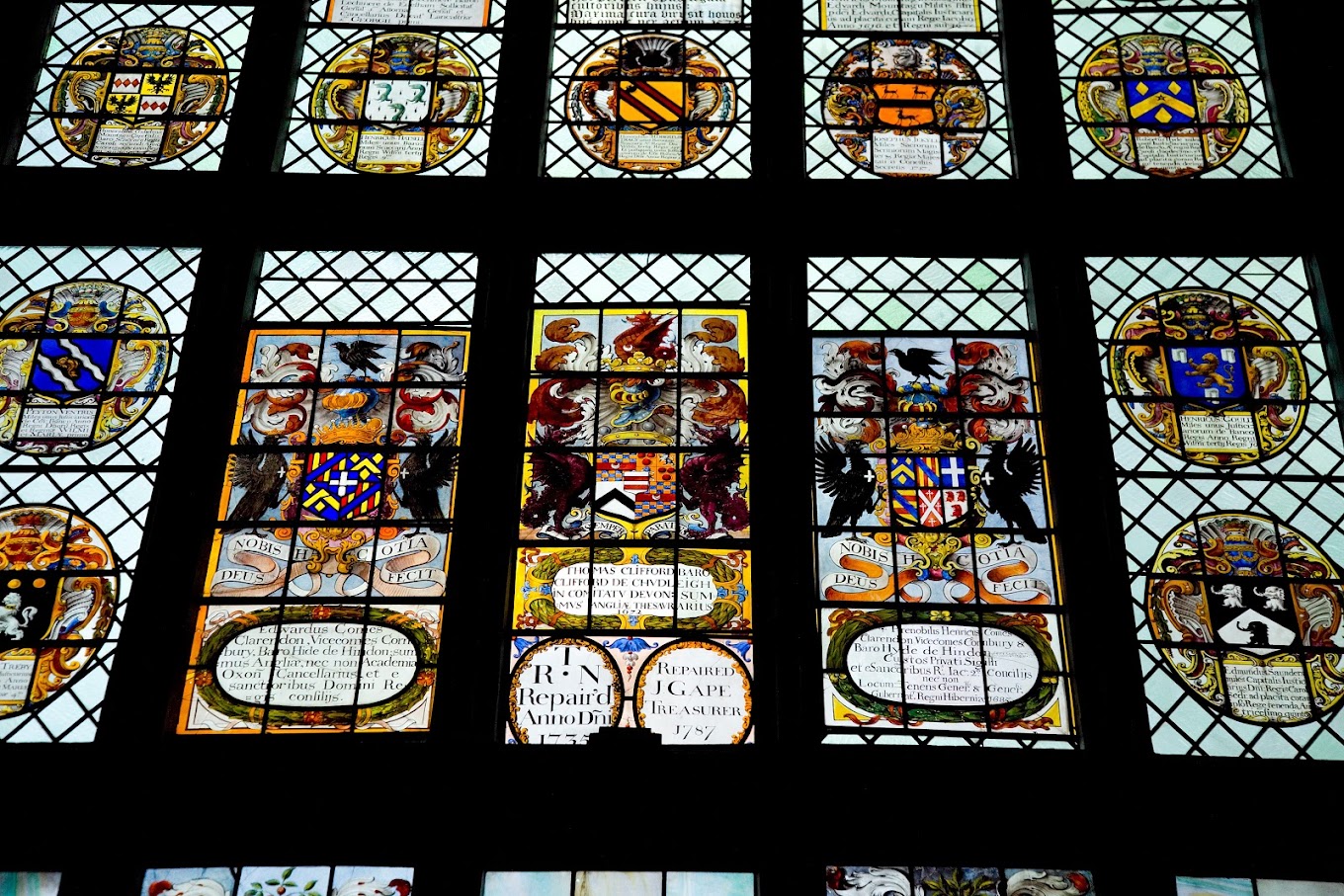

Middle Temple Hall does indeed have huge, great bay windows filled with glass, emblazoned with the heraldic shields of senior members of the Inn. All round the hall, too, there are high windows, climbing up to the hammerbeam ceiling – just like church clerestories.

In 1666, the hall was, thank God, just beyond the western edge of the Great Fire of London and so was spared. It just survived the Blitz and it now looks as good as it ever has in over half a millennium. Happy 550th birthday!

Comments