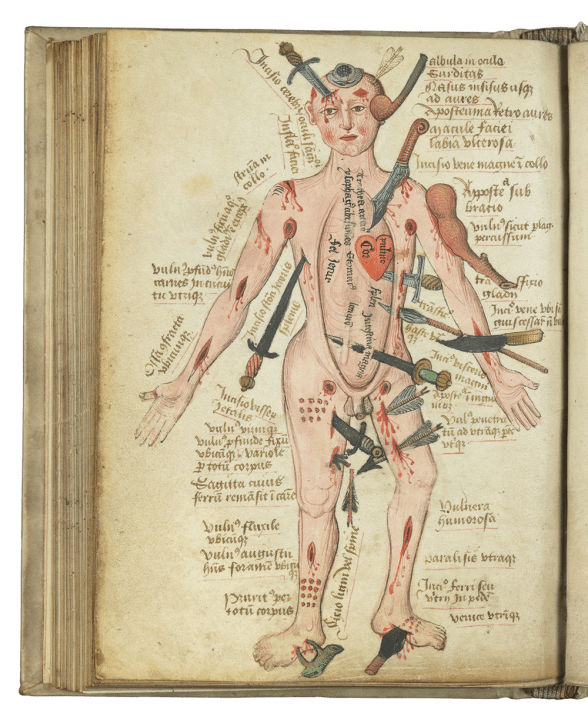

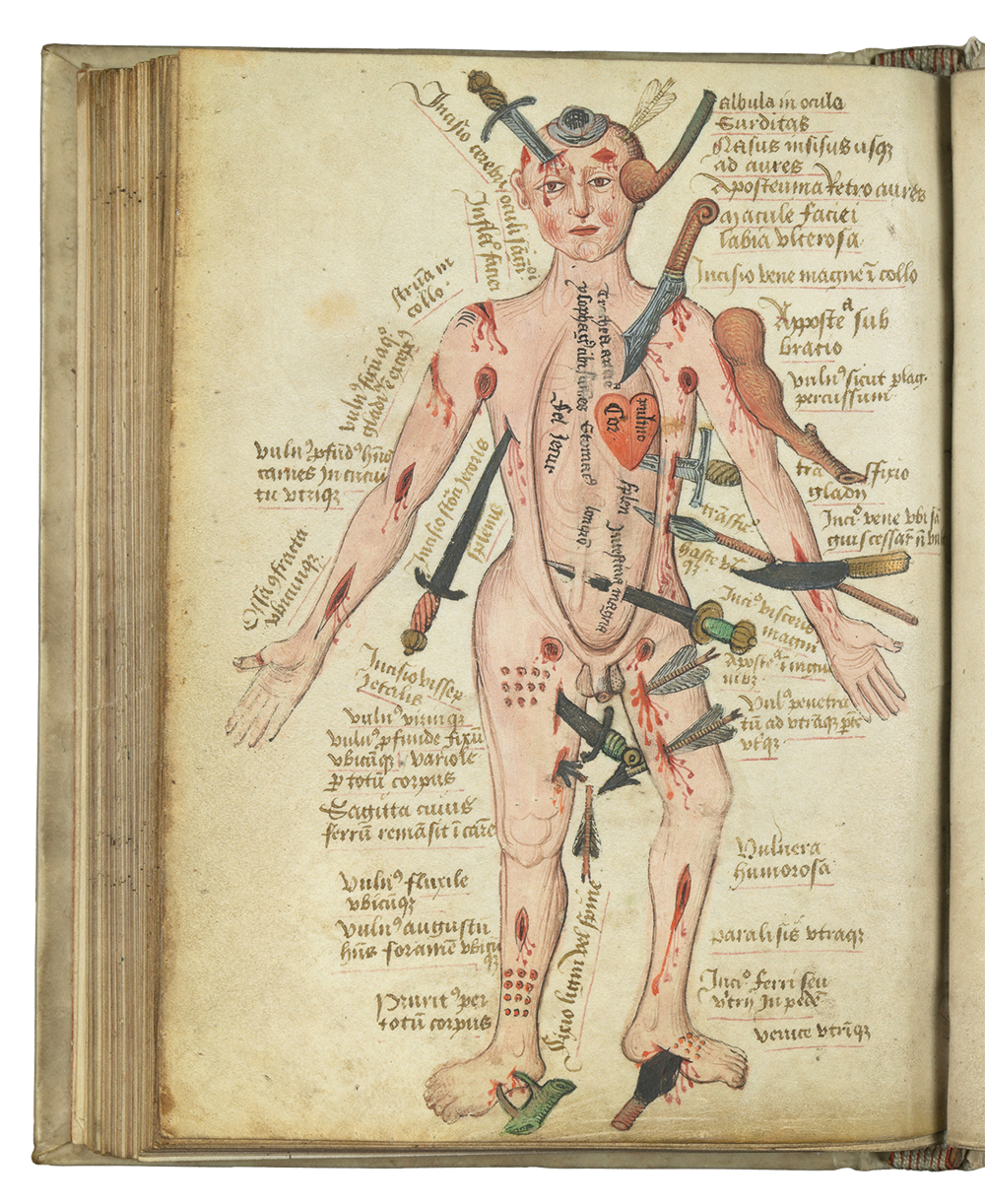

‘Full of strokes and blows/ broken, pitifully wounded’, the man, naked, or almost so, stands full frontal, legs and arms parted, one limb sometimes slightly bent to signal the beginning of a movement. His body is punctured by lesions and wounds, with small depictions of their material causes attached almost as adornment – knives or weapons aimed at cutting and bruising, but also accidental instruments of damage to the skin such as thorns or nails or even living agents – a rabid puppy with sharp teeth. Scratches, buboes and insect bites are also visible.

The image of the ‘Wound Man’ (or rather, images with variations) first emerges at the end of the 15th century in a group of Bavarian medical manuscripts, and has since been reproduced and reinterpreted multiple times throughout Europe in surgical treatises. To us today, these tables offer a striking combination of vividness, human suffering, love of detail, medical knowledge and practicality.

This volume by the art historian Jack Hartnell, the author of Medieval Bodies, is the first extensive collection and analytical discussion of this striking material – and a visual treat. It also offers an insight into the history of European science and early modern intellectual culture. Many of its discussions go even beyond that.

The book is divided into five chapters and an epilogue. Chapter one explores the diagrammatic images of the body which are the antecedents to the Wound Man. He is not born in a void, nor is he simply an isolated manifestation of a catchy idea of how to present medical knowledge to students. The expressive strategy belongs to a larger family of late medieval diagrammatic images of the body, such as bloodletting figures and the Dreibilderseries (‘Three figure series’), many examples of which survive. The series typically consisted of three anatomical tables mapping the human body for medical teaching, sometimes extending to its inner parts, sometimes merely localising medical information on the body’s surface. Appearing in the 13th century, these human figures with their extensive captions conveyed humoral physiology and its diseases, female health and the treatment Christology, of respective wounds, complementing surgical treatises.

Hartnell explains how the Wound Man evolved particularly from the last of the threefold series. At the same time, he persuasively argues that our wounded man unquestionably adds something new. Chapter two explores what this novelty is, focusing on ‘wounds’ as combining physical damage and symbolism, or allegorical intervention in (or interference with) the ‘healthy’ human body. Female bodies are also discussed in a dedicated section. Chapter three looks at wounds as a phenomenological collective or ‘woundscape’, but also examines tools and instruments (medical and martial) and their role in shaping medical doctrines. Wounds are approached from a variety of angles: as experience, as trope, as Christologically meaningful tokens, as medical signs interpreted for diagnosis and prognosis.

The presentation of the human body as a micrcosmic ‘book of everything’ prompts larger philosophical questions

We then move on to the printing age and the greater dissemination of knowledge which accompanied it and the wider diffusion internationally of the Wound Man. A final chapter addresses more theoretical matters of aesthetic purpose or effect, discussing the enduring appeal of the Wound Man by the beginning of the 16th century, when he appears to have become a cultural-historical image dissociated from explanatory or didactic purposes. Three case studies from France, England and Japan expand the story further.

This summary does not begin to cover all the areas touched by the book, which is structured chronologically but emphasises more general questions about the human body and its image. Cultural analysis and art history from medieval times onwards are invoked along the way, with reflections of all sorts attached: from Erich Auerbach’s classic concept of figura, bringing together embodied image, symbolic meaning and prefiguration of the future, to the iconography of Christ’s wounds, to blurring the division between art intended as ‘decoration’ and science intended as ‘content’. More concretely, the suffering implicit in the human image prompts questions about the connection between science and violence, with visual legal testimony in matters of criminal law serving as a suggestive counterpoint. Hartnell’s strategy is one of accumulating snapshots and tracing sections of a larger trajectory. Occasionally, this results in simplification, and the reader is left curious to know more – for instance, on the subject of pain and medicine – but this is a fair price to pay for stimulating reading.

Another fascinating question hinted at is that of gender and genus – women and animals, and their relationship to the wounded male ‘matrix’: how does the relationship to one and the other vary? The postures of the figures vary, slightly but importantly: what of classicism or canonicity vs. prosaicness and almost comical realism? The mapping through wounds conveys pathology, nosology and causes of diseases; but also, before this, instructions for bloodletting and astrological information (a venue of communication with yet another parallel, the human figure of the Babylonian ‘Zodiac Man’). This presentation of the human body as a microcosmic ‘book of everything’ – health and physiology, suffering as accident and disease, therapy and astrological wisdom – prompts larger philosophical questions.

Finally, there is the association of the striking and horrific with beauty and knowledge – its sublimity, to which poetry and art respond more readily than medical treatises can. The poetic quotations and examples from figurative art Hartnell offers provide good inspiration here. I was made to think of the much later venere anatomicae – miniature models of beautiful women, often finely crafted in wood or ivory, whose bellies could be opened to reveal removable individual organs, and sometimes a foetus – created in Florence and widely popular from the end of the 18th century on. Here the combination of dissective anatomy and eroticism is unmistakable. Although obviously not as attractive, the Wound Man, too, has an intentional charm that reaches beyond the usefulness of the information he conveys.

This book offers a stunning selection of visual sources and thoughtful commentary. Anyone interested in medieval history, figurative art, the human body or medicine will wish to return to it again and again.

Comments