Our new king is not, by normal standards, an important intellectual. But it would be churlish to dismiss his thinking as insignificant. Normal standards do not apply to a man who has spent his life earnestly preparing for a grand mythical role.

Some princes have little trouble ignoring the religious aspects of monarchy, instead getting on with hunting, polo, or charity work. But young Charles was a sensitive soul, the sort who struggles to forge an identity. He had intellectual curiosity and a high idea of himself. Charles has shown a real capacity for melancholic detachment, self-scrutiny, angst. That’s not the whole story: as his leaky-pen petulance reminds us, he also has traits of the spoiled boy.

The first important influence on him was Gordonstoun because he was miserable at the school. He was shunned, and treated with defiant roughness: anyone who was nice to him was mocked with slurping noises. This led him to feel like an outsider, at odds with mainstream opinion. Without this dose of adolescent pain, he might have sensibly shied away from taking himself, and his ideas, too seriously. He was already drawn to religion in an aesthetic way. He once complained that worshipping in the sports-hall was ‘hopeless, there’s no atmosphere of the mysterious that a church gives one.’

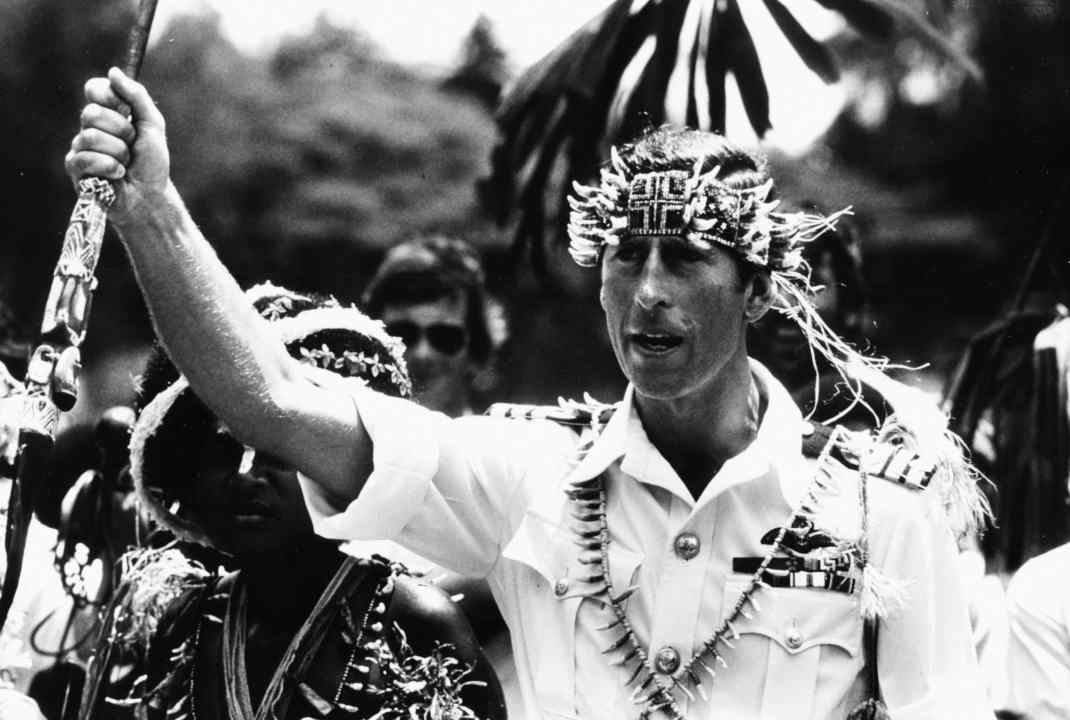

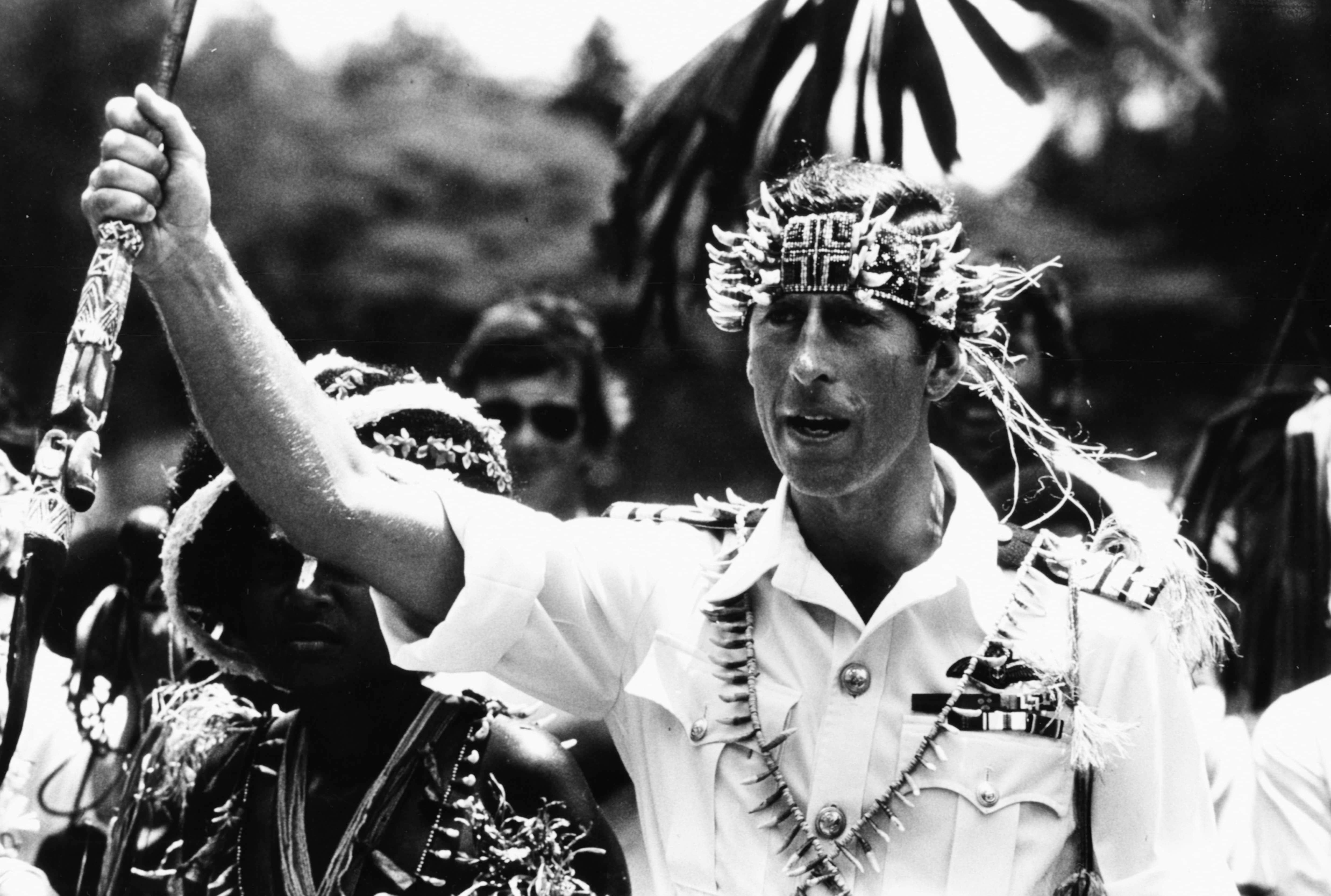

He chose to study archaeology and anthropology at Cambridge, which deepened his interest in non-western cultures. His college chaplain, Harry Williams, encouraged him to take a broad view of religion and was the first to interest him in the thought of Carl Jung. He was also influenced by the eccentric bishop of Southwark, Mervyn Stockwood, whose interests included parapsychology. This acquaintance with 1960s Anglicanism gave him permission to be a spiritual seeker, without fearing a conflict with his destined Anglican role.

By the mid 1970s, the South African-born writer Laurens van der Post became his chief guru. He was a primitivist, a believer in the higher wisdom of tribal culture, especially the Bushmen of the Kalahari, and in the need for civilised people to re-connect with this wisdom. In one of his books, Venture to the Interior, van der Post wrote:

‘We all have a dark figure within us, a Negro, a gipsy, an aboriginal with averted back. And, alas! The nearest many of us can get to making terms with him is to strike up these precarious friendships with him through the black people of Africa.’

His special status forces him to the margins where he found a simple gospel to proclaim

Van der Post spoke of rescuing humanity from ‘the superstition of the intellect’ and of restoring the ancients’ spiritual oneness with the natural world. And he encouraged Charles to find a grand role in this creed: ‘The battle for our renewal can be most naturally led by what is still one of the few great living symbols accessible to us – the symbol of the crown,’ he wrote to Charles.

The prince was encouraged in this Jungian idea of the monarchy by the poet and mystic Kathleen Raine, and by the poet laureate, Ted Hughes, who spoke of its ‘shamanic’ power to unite the national ‘tribe’. Of course this is compatible with traditional monarchism, but the pagan tinge has a freshness that appeals beyond conventional conservatives. Charles had begun to think like a poet who feels licensed to dissent from the mundane intellectual habits of his peers. This emboldened his advocacy of alternative medicine, architectural traditionalism and environmentalism, all central to his image by the mid-1980s.

But he was generally assumed to be a traditionalist Anglican, an image he encouraged by championing the Prayer Book. This changed after his televised interview with Jonathan Dimbleby. As well as hoping that he might be ‘defender of faith’, he admitted to a certain restless detachment from Anglican orthodoxy: ‘I’m one of those people who searches’, he said. He would like to be:

‘Defender of the divine in existence, the pattern of the divine which is, I think, in all of us, but which because we are human beings can be expressed in so many different ways.’

He soon became bolder about his message. In 2000, he called for a new ‘sense of the sacred in our dealings with the natural world, and with each other. ‘If literally nothing is held sacred any more… what is there to prevent us treating our entire world as some “great laboratory of life” with potentially disastrous long-term consequences.’ Two years later he put the emphasis on his own vocation:

‘I have come to realise that my entire life has been so far motivated by a desire to heal – to heal the dismembered landscape and the poisoned soul; the cruelly shattered townscape, where harmony has been replaced by cacophony; to heal the divisions between intuitive and rational thought, between mind and body, and soul, so that the temple of our humanity can once again be lit by a sacred flame.’

Charles wanted then to be a sort of Blakean prophet. On one level this is a strange desire for a man at the very pinnacle of the British establishment. But on another it makes perfect sense. He had been raised to feel that he had a sort of religious authority. But how could this find expression unless he stepped outside of Anglican orthodoxy?

The breakdown of his marriage led to a tense relationship with Anglicanism, especially when some clerics questioned whether an adulterer should become king. Consciously or not, his inter-faith idealism was an up-yours to Anglicanism, a way of outdoing it. No bishop could offer such positive rhetoric about other religions – Charles could seem to rise above his particular tradition and assume the mantle of high priest of global spirituality.

In the 1990s he began to speak of Islam as especially worthy of respect, even suggesting that it exhibited what modern Christianity had lost, ‘a metaphysical and unified view of ourselves and the world around us’. In another speech he suggested that more Muslim teachers in schools could teach us ‘how to learn with our hearts, as well as our heads.’ His Islamophilia was only slightly muted by 9/11, despite much right-wing disquiet. He began to dial down the Orientalism, to put more emphasis on what the Abrahamic faiths have in common, and the danger of false interpretations of Islam. But his insistence on the core wisdom of Islamic tradition remained strong. Again, his Islamophilia should be seen in relation to his semi-detachment from Anglicanism and the role he felt this gave him. He felt that British Muslims were in need of reassurance from a representative of British tradition and that it could not come from politicians or bishops. It was a task for a different sort of spiritual leader, above the political fray and also above narrow religious allegiance.

Charles’s creed can be summed up thus: there is divine wisdom in all human traditions, until modernity comes along and rips us away from any semblance of harmony with nature. He often attacks ‘modernism’ as soulless, narrowly rationalist, individualistic. Of course this overlaps with all sorts of religious conservatism, but in its inter-faith emphasis it is particularly close to a movement called ’perennial philosophy’, which is partly inspired by René Guénon, a Frenchman who converted to Sufi Islam in the early 20th century. It’s basically Theosophy but with less of an esoteric aura. In 2006, Charles addressed a perennial philosophy, or ‘traditionalist’ conference. The movement was not motivated by ‘nostalgia for the past, but a yearning for the sacred’, he said; it sees ‘tradition’ in terms of ‘a metaphysical reality’ and ‘underlying principles that are timeless.’

Charles certainly has much in common with the post-liberal movement: both denounces economic and social liberalism; both trace the rot to the secular Enlightenment and hope to restore the medieval assumption of the unity of God and reason. But there’s a major stylistic difference. Post-liberals try to make this into a coherent vision through polemics against secular liberalism and advocacy of a conservative form of Christianity (though presented as radical rather than conservative). Charles floats away from such discourse, knowing that he must not be pegged as any sort of conventional religious conservative or critic of liberalism.

In 2010 he wrote (with two co-authors) a book called Harmony. It begins with a call for ‘revolution’ – a turn away from destructive materialism towards traditional spirituality. It attempted a coherent vision, relating his belief in traditional architecture and aesthetics to his belief in the authority of nature, whose geometrical patterns are manifestations of the divine. Of course the grand ambition opened him to ridicule. ‘There are, to be sure, limits to Charles’s revolutionism’, wrote Terry Eagleton.

‘He wants the kind of change radical enough to do away with polluters and modernist architects, but not radical enough to do away with himself. Meanwhile, he is eager to share his thoughts with us on Francis Bacon’s Novum Organum, Ficino’s tome on Platonic theology, Marinetti’s futurist manifesto and a number of other texts he has almost certainly not read.’

The prince’s own contribution to the book probably amounts to ‘a number of high-minded platitudes reminiscent of a Get Well Soon card.’ Like critics on the right, he charged Charles with political naivety: ‘The prince is darkly suspicious of economic growth – which is to say of other people’s hunger for possessions rather than his own.’ According to Max Hastings, parts of the book resembled ‘the ravings of a Buddhist mystic.’

Was Eagleton right to imply that Charles, not being a proper intellectual, should keep his thoughts to himself? Such criticism feels a bit beside the point. The fact is that Charles does not fit into the normal categories, of academic or poet or politician or pundit. Charles-speak is undeterred by conventional ripostes; those who mock reflect the existing intellectual order, in league with soulless materialism.

Charles is an evangelist, not an intellectual. He is not interested in the open-ended exploring of ideas, like the philosopher-rulers of the Enlightenment era. Instead he has a message to impart. And he is not concerned to make this message as intellectually robust as possible, like the normal philosophical writer. His role has detached him from the normal cut and thrust of intellectual debate and this has become part of his message: that conventional modes of argument are inadequate. It is more important to have faith in the resurrection of divine harmony than to be able to present the message in an intellectually rigorous way. No such presentation of this faith will ever satisfy the nay-saying rationalists, secularists and religious exclusivists.

Charles felt called to be an innovative religious thinker, but his role as head of the Church of England subtly barred him from the debates of mainstream theology. His special status forces him to the margins where he found a simple gospel to proclaim. The phrase ‘natural religion’ is a good summary. It used to mean the creed that underlies all the major religions that comes naturally to humans. But its other meaning, of reverence for nature, is just as important to him. This is not a bad passion for a king to have. It’s a creed that commands respect – even if most of us feel it’s impossibly woolly.

Comments