Theresa May’s awkward dinner date with Jean-Claude Juncker stole the headlines, but there was another Brexit development that passed with much-less fuss: the European Union’s plan for Ireland to reunite after Brexit, which it inserted quietly into its negotiating guidelines. Few in Britain paid much attention to it. Across the Irish Sea, it was a different story. Among Catholic communities, there is growing hope that Brexit could be the issue which finally sees partition end on the island. Yet within Protestant communities, there is a growing fear that the EU is using Brexit as a tool to sneak through Irish reunification. The British government appears to be doing precious little to stop it.

The issue of Irish reunification was included in Brexit negotiating guidelines this weekend at the behest of Ireland’s Prime Minister. Enda Kenny said that he didn’t see Irish reunification as imminent but demanded that it be treated as a serious prospect, and the legal and political groundwork start in earnest. Whether from a sincere belief that Irish reunification is possible now, or because of a more mischievous desire to undermine Britain’s negotiating hand, the other EU states have agreed.

The guidelines made it clear that in the event of Irish reunification, the country would follow a similar model to Germany after the fall of the Berlin wall. In such an event, Northern Ireland could seamlessly rejoin the EU as part of a united Ireland, rather than having to reapply for membership. The plan does not alter the constitutional status of Northern Ireland, where the Good Friday Agreement remains the key legislative framework, which says that only a majority vote in Northern Ireland can see the region leave the UK. Nonetheless, it was still a bold and highly controversial step.

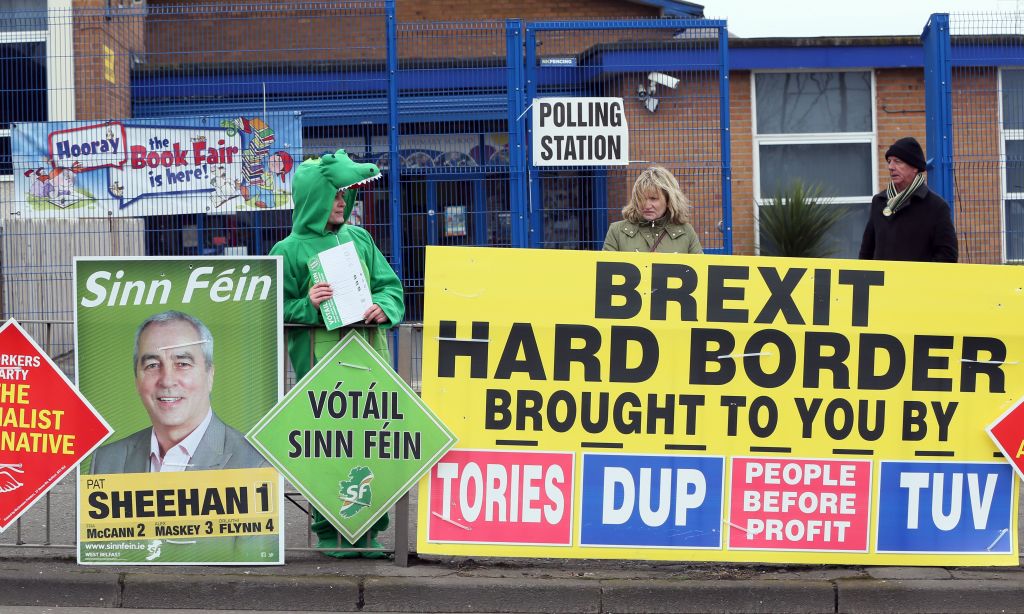

After all, by including mention of Irish reunification in its Brexit plan, the EU has said the unthinkable – and created panic among unionists in Northern Ireland. Higher birth rates among Catholics mean that Protestants will no longer make up the majority in Northern Ireland after 2021. To this backdrop, Brexit now adds further momentum to calls for Irish reunification. Many – especially Northern Irish Catholics – fear a hard border will return after EU withdrawal; both a logistical nightmare and political sore point. Finally, in March of this year unionist politicians at Stormont saw their majority end for the first time since Northern Ireland was created, after a Sinn Féin surge.

The idea that Ireland could reunite has been brewing in recent years. However, by outlining a specific model of reunification the EU has stirred the pot immensely. While many may profess a desire for reunification, most nationalists and Republicans in Northern Ireland are altogether more vague when it comes to the exact details of when and how it would come about. Even Sinn Féin, the leading Republican party on the island, have failed to back up their emotional passion for Irish reunification with much in the way of planning or specifics. Yet by calmly and clearly outlining a legal and political framework for Irish reunification, the EU has gifted the Republican cause a blueprint for a united Ireland. It has also helped lift the topic from toxic and tarred debates related to the Troubles and allowed its supporters to reframe it as a Brexit issue, far removed from the days of Irish republicanism’s violent past.

The news has, naturally, been met with outrage by unionist politicians in Northern Ireland. The country’s former first minister David Trimble said in response:

‘From the point of view from the Irish there is no need for them to introduce this. It is actually playing games with nationalist feelings and I wonder why the Irish government is doing this and why Europe is going along with it.’

The Ulster Unionist Party MLA Doug Beattie echoed his concerns, saying that:

‘It is sad that some are opportunistically using Brexit to try and unpick the union’.

But the response from the British Government has been slower. Theresa May has shown scant interest in Northern Ireland since entering Number 10 – even taking a laissez faire attitude as power-sharing collapsed back in January. With Brexit to get on with, and now a snap general election to win, it is unlikely that her disinterest in Northern Ireland will change. This will only add further panic to Northern Ireland’s unionist community, many of whom fear, rightly or wrongly, that the EU is using Brexit to swoop in and create a united Ireland. If left to stew further, it is likely that this paranoia will grow – damaging Northern Ireland’s relationship with the British government during what is shaping up to be an incredibly testing time for the Union.

Comments