The Edinburgh International Festival opened with John Tavener’s The Veil of the Temple, and I wish it hadn’t. Not that they were wrong to do it; in fact it was an heroic endeavour. Drawing on three large choirs, members of the Royal Scottish National Orchestra and a sizeable team of soloists, this eight-hour performance was the sort of occasion that justifies a festival’s existence – the kind that, done well, can transform your perceptions of a work or a composer. It was certainly done well, and it certainly transformed mine. I’d never much minded the music of John Tavener. By the fifth hour of The Veil of the Temple, I was beginning to detest it.

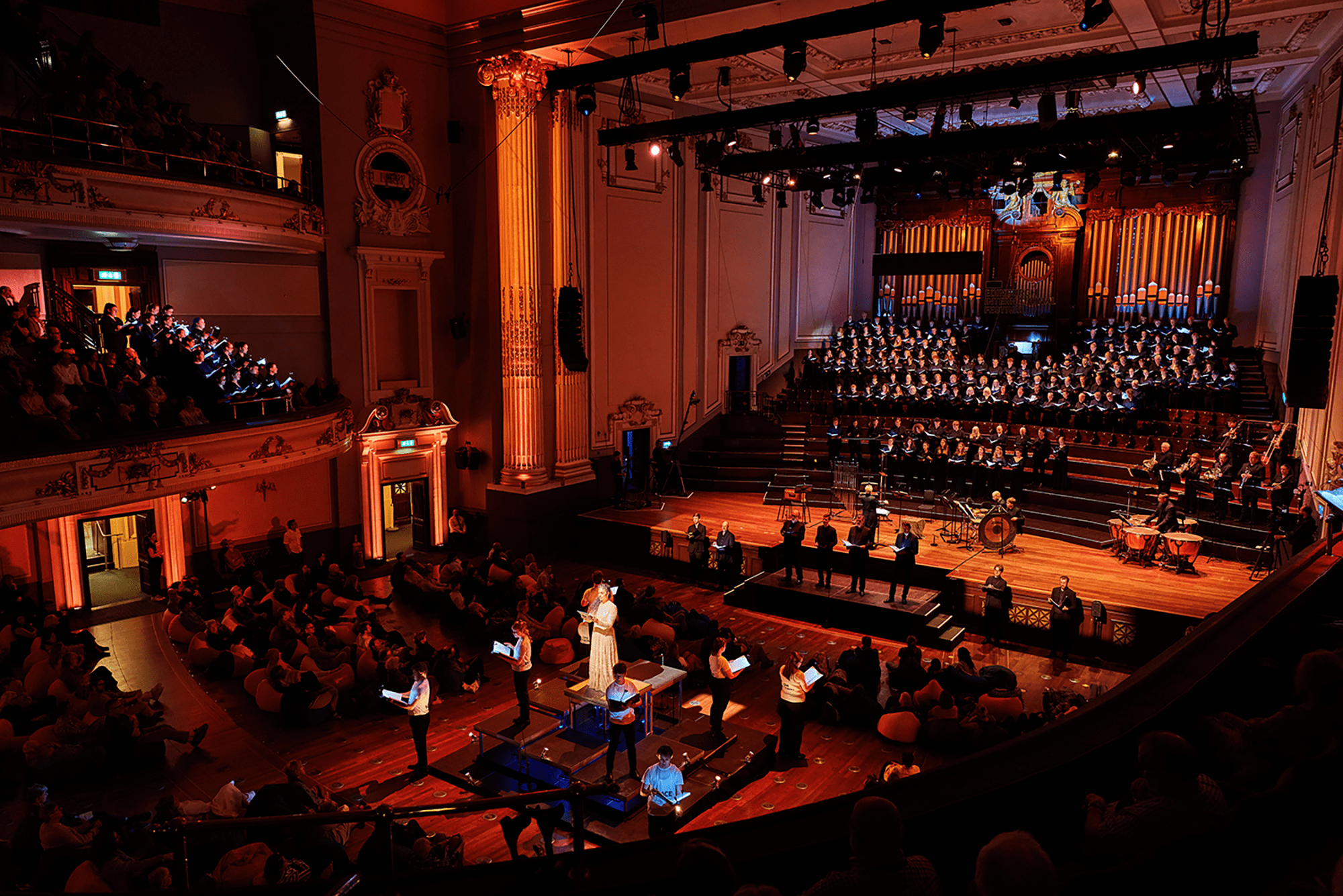

To Tavener’s many fans, I can only apologise, pleading the defence that musical marathons do not usually trouble me (just try and keep me away from a Götterdämmerung). Credible colleagues described The Veil of the Temple as a masterpiece, and the EIF, clearly, was pushing the boat out. They’d replaced the stalls of the Usher Hall with beanbags and the Festival’s artistic director Nicola Benedetti gave a preliminary pep talk, urging us to come and go as we pleased. (The Ladyboys of Bangkok were performing just across the road).

Again, it was impressively done. Tavener created the piece in 2003 as a dusk-to-dawn vigil in the Temple Church, and while the Edinburgh performance ran from 2.30 p.m. to 10.30 p.m. the director Thomas Guthrie had been engaged to recreate that sense of ritual. Choirs processed around the hall; there were lighting effects and at the start of each new section a soloist lit a candle. Sofi Jeannin conducted unflappably, and the Monteverdi Choir handled the trickier passages with its usual finesse. The National Youth Choir of Scotland sounded luminous and utterly tireless, while the Festival Chorus gave it their best shot. The soloists sang with conviction, and the occasional solos from the duduk player Hovhannes Margaryan were ravishing.

But still: the tedium. God, the tedium. Satie aside, composers who operate over an epic span of time generally seek to create a sense of movement; of growth. Not Tavener. He begins with a soprano solo, a blast on a Tibetan temple horn and a bell, before working through an hour-long meditation on a mish-mash of religious texts. Some are delivered in lush, melismatic choral harmonies, others are chanted unaccompanied and some are simply intoned at excruciating length on a single note. That was the first cycle. Then the bell clanged, the horn bellowed, and Tavener moved on to the second, which was almost identical. And then the third, and so on: six huge, slowly thickening variations on material that was wearing thin within the first hour.

There is no fast music to speak of, and Tavener’s choral rhapsodies typically unfold over a static drone. The music just stands there, revolving and self-regarding. Individual sections are gorgeous; you could pull ten minutes out of any choral episode and create an exquisite self-contained miniature. But repeated at this sort of length, it felt like being caressed with velvet until your skin rubs raw and starts to bleed. Seated upstairs in the middle of a row, I was effectively locked in place, screaming inwardly. A ten-minute break five hours in allowed a relocation downstairs to the beanbags, where the knowledge that I could (if necessary) escape made the ordeal more bearable.

Eight hours of glassy-eyed sonic masturbation under a monk’s habit. The things we do for art

There was a pay-off, of sorts. After seven hours there’s a seismic shift: brass and percussion enter and Tavener co-opts Tristan und Isolde and The Waste Land to generate the catharsis that his own ideas are impotent to express. Even that outstayed its welcome, though the audience exploded in cheers (roughly two thirds of them stuck it out to the end). I just kept thinking of Archbishop Colloredo’s injunctions to Mozart about keeping sacred music concise. Tavener professed the Orthodox faith but western churches have traditionally regarded ostentatious displays of piety as obnoxious, if not actually sinful. And this one went on for eight hours. Eight hours on a summer day in a beautiful city. Eight hours of glassy-eyed sonic masturbation under a monk’s habit. The things we do for art.

That doesn’t leave much space for the Three Choirs Festival, where Samuel Coleridge-Taylor’s 1903 passion oratorio The Atonement (think Parry rescored by Elgar) received an affectionate and energetic revival under Samuel Hudson, with a spectacular solo turn as Pontius Pilate from the great Mark Le Brocq. Poor Coleridge-Taylor. He rambles, for sure, but he strives, too, and at his best he touches the heart. How harshly we judge our second-rate romantics! And how we indulge our celebrity minimalists. No one’s going to programme The Atonement at Edinburgh any time soon, but I’d re-hear it three times in succession sooner than endure another five minutes of The Veil of the Temple.

Comments