Writers, I hope we can all agree, should be paid for their work. That’s the principle behind the law of copyright, and it has held for more than a century. We owe it to (among others) Charles Dickens and Frances Hodgson Burnett. But what about when their work is quoted by other writers?

You’re allowed to quote only a certain proportion of a work before you need to pay the rights holder

This week I published a new book in which I spend a lot of time discussing the work of other writers. The Haunted Wood: A History of Childhood Reading is a canter through children’s literature from Aesop and Anonymous to J.K. Rowling and Julia Donaldson. A lot of what I wanted to discuss was out of copyright (it’s perhaps in bad taste to thank Margaret Wise Brown for having died in 1952 rather than living on till 1954, but it did let me do a line-by-line close reading of her immortal masterpiece Goodnight Moon); a fair bit was not.

It was both a courtesy and the right thing to do to seek permission to quote their work. And the process was mostly rather heartening. Not much more than £100 secured me the right to quote the stanza of W.H. Auden’s wonderful ‘September 1st, 1939’ from which my book takes its title as the epigraph. I consider that a bargain. Julia Donaldson was super-generous in allowing me to quote from The Gruffalo. The great Allan Ahlberg asked a peppercorn for me to quote a few lines from Each, Peach, Pear, Plum.

But the A.A. Milne estate was asking what seemed to me a crazy amount of money to quote a single couplet from that poem about Christopher Robin saying his prayers – and my publishers advised me, if I didn’t want to pay, to snip it out. Which I did. The rights holders for another author of verse, who shall remain nameless here, not only asserted that ‘fair dealing’ legislation – the provision that allows you to quote without permission – didn’t apply to their author but claimed an absolute right of veto on any quotation for ebooks or audio. Reader, despite my passage on that author being a very close reading of the prosody, we sorta caved.

For here’s the thing. When the manuscript came back to me, marked up by my publisher, every instance of a line of poetry from an author still in copyright arrived with a positive forest of red flags. Poetry, I was told, is very dangerous. Not as dangerous as pop lyrics (everyone agrees that they are ‘a nightmare’, and I sadly had to forgo pairing W.H. Auden with the 1980s prog-rock outfit Marillion) – but much riskier than prose.

This strikes me as curious and a little troubling. The fair-dealing rules are sensible, but they are vague. One important aspect of them is that you’re allowed to quote only a certain proportion of a work before you need to pay the rights holder. That proportion is usually said to be 10 or 15 per cent; but nobody knows for sure (and that’s not even a couplet from a sonnet). Another, again fair enough, is that what you do won’t affect the market for the original work: that you’re not eating the rights holder’s lunch.

Between them, these provisions articulate a reasonable set of boundaries. I can’t, for instance, profit from compiling an anthology without paying the rights holders. I can’t add a fancy epigraph to my own book without offering the rights holder an agreed pourboire. And I can’t republish most of someone’s novel, add footnotes or commentary, and claim it’s for literary-critical purposes.

But for literary critics and literary historians to do their work, they need to be able to quote, sometimes extensively. That goes double for critics of poetry – which, as well as being famously resistant to paraphrase, has formal properties that can only be analysed with direct reference to the text itself. So if the instincts of publishers are right, and the law really does look differently on poetry than on prose, it’s an intellectually insupportable and slightly disturbing situation.

For a start, the implication is that copyright lawyers have succeeded in establishing an absolute distinction between poetry and prose where generations of literary theorists have failed. Of course, one sort of poetry is the type that, in the formulation of the late Auberon Waugh, ‘rhymes, scans and makes sense’; but it’s not the only sort. Free verse is, or can be, very close to prose. ‘Prose poetry’ is a thing. But even should we imagine poetry and prose are formally separable, the idea that there’s a distinction of legal status between them is bizarre.

It can’t just be the issue of the amount quoted as a proportion of the overall work. Though some poetry is short (which of course will affect how much, as a proportion of the original work, is available under fair dealing: critics will need to be careful with haikus), some poetry is very long. It seems perverse and unwarranted that you could quote great paragraphs of Vikram Seth’s novel A Suitable Boy in a critical work about Seth without a by-his-leave, but that you’d need to avoid quoting more than a line or two from his verse novel The Golden Gate.

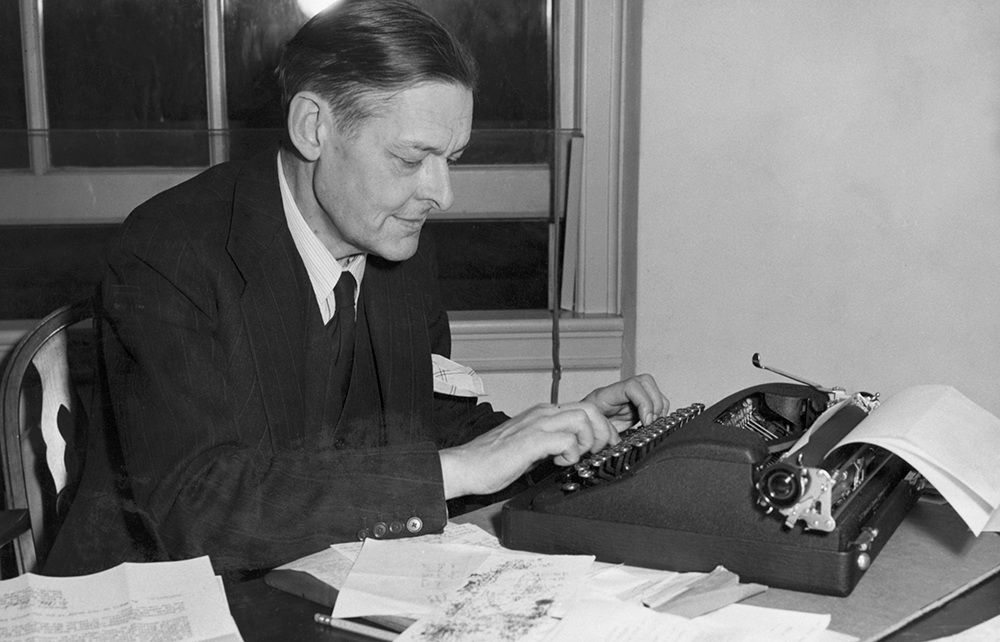

This isn’t a purely theoretical concern. When the T.S. Eliot estate refused Peter Ackroyd, my predecessor as The Spectator’s literary editor, permission to quote from the work for his 1984 biography, it made his life distinctly difficult. (Never mind that Eliot himself wasn’t exactly averse to lifting the odd line from another writer.) Taken to its logical conclusion, it implies that poets – unacknowledged legislators as they may be in other respects – have a unique power of veto over serious literary criticism of their work.

Back to that grey area. The problem here is not exactly the law. The problem is that nobody wants to test the law. As media lawyer David Hooper put it when I asked him: ‘Copyright law is distinctly unpredictable and expensive to litigate, which puts the copyright holders in quite a strong position.’ Publishers prefer not to take the risk, in other words. Hence the ancestral terror of quoting poetry.

For my part, it seems to me that in the interests of the commonwealth of knowledge these questions should be made more explicit. Fifteen per cent? Ten per cent? Five per cent? As a proportion of a single poem, or of a poetry collection? It’d be good to see more clearly where the tramlines are. But who wants to be the test case? No, me neither.

Comments