Gaily into Ruislip Gardens runs the red electric train…

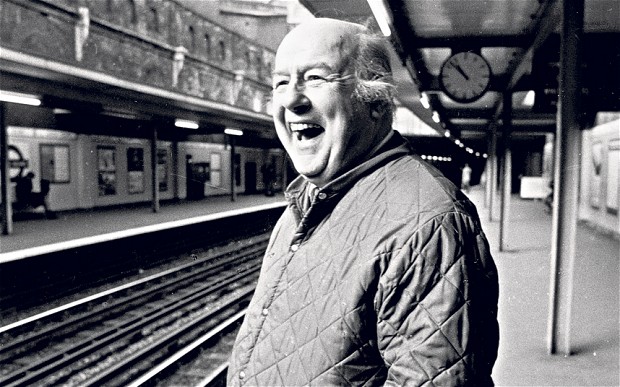

Near the end of the Metropolitan Line, where London dwindles into woods and meadows, stands a Tudor manor house, built within the moat of a motte-and-bailey castle. Now a quaint museum, charting the history of the farms that once surrounded it, this modest landmark shares its name with the local Tube station, Ruislip Manor. A century after they built it, the railway that runs through here still feels out of place. There are fields on one side, suburban semis on the other. Welcome to Metroland, the bizarre no-man’s-land between town and country, created by the Metropolitan Railway, which celebrates its 150th birthday this year. The Metropolitan Railway is best remembered as the enterprising company that built the world’s first underground railway, between Paddington and Farringdon (opened in 1863 and still going strong today). Yet the Met’s other innovation was arguably even more influential. When the company expanded into Middlesex, laying new lines across virgin countryside, it bought up the adjoining farmland and covered it with mock-Tudor housing estates. Has there ever been an architectural style less prestigious, yet so attuned to British tastes? As green and pleasant Middlesex became a labyrinth of cul-de-sacs, Metroland spawned a new aesthetic, and a new way of life. These cod-bucolic conurbations set the standard for 100 years of British housebuilding. Today, Britain is awash with modern versions of Metroland. Two years ago, I moved to the heart of Metroland — Ruislip, to be precise. It was the usual story. With the proverbial wife and two children to support, I’d been priced out of central London. Less than ten miles from my old home in Hammersmith, Metroland felt like another country. It felt like the England I remembered from my childhood — humdrum and discreet. Nobody in their right mind would call it beautiful (Ruislip’s five Underground stations have buried the original medieval village beneath an avalanche of crazy paving) but between the privet hedges a few traces of rural England survive. Tube trains rattle through fallow fields, past rows of tidy bungalows. ‘In the country but not of it,’ as the novelist Leslie Thomas put it, it feels familiar yet incongruous, like the landscape of a dream. For trendy Londoners this is nowheresville, but wherever you live, it looks as though we’re going to have to get used to it. As our politicians urge developers to build on so-called ‘boring’ fields, Metrolands such as Ruislip will become an increasingly familiar model for the way we live today. In another 100 years, will all of England look like this? Metroland was an intrinsically English invention, selling a cut-price version of that Edwardian nirvana — the country cottage with honeysuckle round the door. Balladeers wrote songs about it, with whimsical titles like ‘My Little Metroland Home’ (‘I know a land where the wild flowers grow’). While Continental architects built huge high-rise blocks intended for mass habitation, Metroland’s house style was nostalgic and individualistic, English Conservatism writ small. These proud new owner-occupiers were urbanites, but the lifestyle they aspired to was pastoral. ‘Charming country houses, built of All-English materials,’ promised the brochure. Yet Metroland was an artificial construct, as synthetic, in its own way, as the futuristic fantasies of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis. Even the name was an adman’s slogan, coined in 1915. A rural idyll within the city limits was always a false promise. Of course it could never really work. Nevertheless, between the wars, Metroland became the template for London’s ravenous expansion, as the capital swallowed Middlesex, and ate into Bucks and Herts. Metroland turned Domesday hamlets into halts on the new railway, then into vast swathes of suburban sprawl. These places, these non-places, were defiantly unfashionable, yet they were profoundly English in a way that Art Deco apartments never were. Is there any Englishman who doesn’t dream of owning his own house in the country? For millions of commuters, Metroland was the next best thing. Yet suburbia is self-defeating, destroying the tranquillity it covets. As London stretched out into the country, the countryside retreated. Metroland was an illusion, a vision of Arcadia that remained for ever out of reach. One man who understood the tragicomedy of Metroland was John Betjeman. His poignant poems championed its beauty and absurdity in verse. Forty years ago, this poetic vision found its expression in a film he made for the BBC, which you can still see, if you’re prepared to fork out for the DVD. It’s a reminder of how much television has deteriorated since that golden age, when the BBC allowed great thinkers such as Betjeman (and Kenneth Clark and Jacob Bronowski) simply to talk to us, and trusted us to sit and listen. The content of Betjeman’s film reveals a parallel decline in Metroland. Today’s suburbs may be smarter, its houses may be worth more money, but Betjeman’s scruffy hinterland seems more friendly than the place where I live today. Like Metroland itself, Betjeman’s commentary is a strange amalgam — a subtle blend of poetry and prose. As his warm voice washes over me, I realise, to my surprise, that I’ve become a bit-part actor in his drama: ‘city clerk turned countryman, linked to the metropolis by train’. As he boards the train at Baker Street, and travels through Neasden, and on to Amersham, I see my own life rushing past. Moving to Metroland is the kind of compromise that comes with middle age. Betjeman’s documentary depicts a country that’s also beginning to feel its age. The BBC called Metro-land an ode, but it’s really more of an elegy — a wistful epitaph for an England forsaken long ago. It was already disappearing when Betjeman made his travelogue. Forty years later, it has almost vanished. How did we lose it, you wonder, as you watch this film. Has it really gone for good? Britain’s last great poet laureate certainly seemed to think so. ‘Goodbye bright hopes and overconfidence,’ he says, sadly. ‘In fact it’s probably goodbye England.’ As he remembers pastures ‘that once were bright with buttercups’, you wonder how many more meadows will be buried beneath tomorrow’s Metrolands. There are fields full of wild flowers behind my bland suburban home in Ruislip. The woods beyond seem to stretch on for ever, though Watford is only a few miles away. Striding out into open countryside, leaving Metroland behind me, I recall what Sir John Betjeman said as he surveyed the city’s outer limits: ‘Grass triumphs, and I must say I’m rather glad.’ Or, as he put it in his poem ‘Middlesex’:Betjeman’s poignant poems championed Metroland’s beauty and absurdity in verse

Out into the outskirt’s edges, where a few

surviving hedges Keep alive our lost Elysium — rural Middlesex again.

Comments