If you wish to know how to become a master negotiator, a formidable body of books will now offer to train you in that art, but I’m not entirely sure it can be taught. The greatest natural asset, I suppose, is the ability to enjoy the game: the performative mulling, tough-talking, buttering-up, pitching of curve balls and – when absolutely necessary – flamboyant execution of a real or bluff exit. Yet even for those of us who are clumsy and reluctant hagglers, the mechanics of striking a deal can be fascinating. This is the stuff of the Dealcraft podcast, hosted by Jim Sebenius, a professor of the Harvard Business School, and himself a high-flying negotiator. Via ‘interviews with the world’s greatest dealmakers and diplomats’, he aims to distil ‘practical insights for listeners to apply in their own toughest negotiations’.

This could act as tip number one: if you have a squeaky, grating voice, take it down a few notches

The first thing to notice about Sebenius is that he has a tremendously gravelly, reassuring and slightly soporific voice, suggestive of expensive Scotch and knowing observations in oak-panelled boardrooms. Indeed, it could easily lull a susceptible opponent into signing all sorts of agreements under the temporary delusion that everything Sebenius proposed made obvious mutual sense. I suppose this could act as tip number one: if you have a squeaky, grating voice, take it down a few notches. Before long other anecdotes and lessons are coming thick and fast, courtesy of his stellar array of guests, including Hillary Clinton and the late Henry Kissinger.

One retired ‘music-industry super-lawyer’, John Branca, describes the challenges of working for Michael Jackson at the height of his Thriller era. Jackson kept nagging Branca to get hold of the film canisters of the ‘Thriller’ video, which he duly did. But in numerous whispery but insistent telephone conversations, Jackson started demanding that Branca destroy the film, something the lawyer was understandably loath to do. It emerged that Jackson, a Jehovah’s Witness, had decided that the occult themes of ‘Thriller’ might be seen as promoting demonology, and therefore potentially cost him a future place in heaven. Branca’s route out of the dilemma was to concoct a story that the actor Bela Lugosi who played Dracula – a particular favourite of Jackson’s – was a strongly religious man who shared Jackson’s unease about the supernatural, but had got round his own ethical problem by posting a personal disclaimer at the start of his films.

Jackson agreed, the disclaimer appeared, and the ‘Thriller’ video catapulted his career into the pop stratosphere. Sebenius touches on the morality of making things up in order to further one’s negotiating aims, but concludes that although ‘ethical questions frequently arise in negotiations’, the key thing here is that the Lugosi lie didn’t hurt anyone.

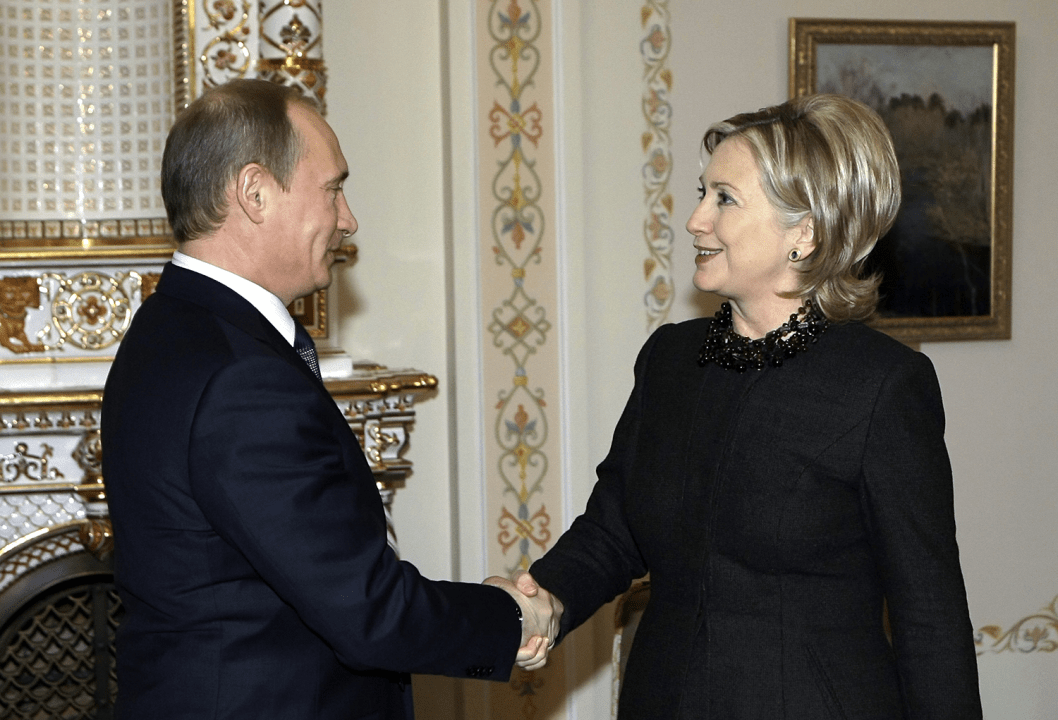

He has plenty of good advice, which can apply even to awkward conversations in everyday life. I particularly liked ‘Become comfortable with silence in negotiations’, since we have surely all encountered those individuals who deploy their silence as a test of nerves, waiting for the other person to crack and start jabbering nonsensically. Then there is the instruction to ‘establish a source of commonality’ even with tricky people: Hillary Clinton describes how – in the days when it was still deemed possible to negotiate with Vladimir Putin – she finally found a crack in the Russian President’s macho surliness by complimenting him heavily on his efforts to conserve Russian wildlife such as the Siberian tiger. Putin briefly came alive, she said. He pressed a button that opened the door to his inner sanctum, which had a huge map of Russia on the wall, and pointed out where he was soon travelling with the aim of tagging polar bears. Turning to Clinton, then US secretary of state, he asked: ‘Would your husband like to come?’

Elsewhere, in the chaotic and often impractical pantheon of pop and rock stars, Bruce Springsteen has always seemed like a rare front-man with the practical nous to negotiate the small print of a contract: his long-standing nickname ‘The Boss’ – which he has said he hates – reportedly came about in his early days with the E Street Band, when he received cash payments from promoters and distributed them among his bandmates. That’s part of the reason, perhaps, why the bard of blue-collar America has an estimated wealth of more than $1 billion.

And now he is 75. In honour of his birthday, the BBC put out a compilation of radio and television interviews featuring Springsteen in conversation with everyone from Bob Harris to Kirsty Young and Graham Norton. The nature of these tribute programmes is that enticing snippets of conversation are spliced with songs, without the listener getting much chance to absorb the wider context or chronology of the subject. But it’s a pleasure nonetheless: Springsteen proves an engaging and eloquent interviewee, and the songs still stand the test of time. In hits such as ‘Born To Run’, ‘Badlands’ and ‘Dancing in the Dark’, he caught the doomed poetry of the pretty check-out girl and the small-town garage mechanic: no one has better voiced the restless, hopeful desperation of working-class Americans trying to escape a future they could already sense tightening into a trap.

Comments