‘In matters of criminal justice,’ said NatWest Three defendant David Bermingham after a London court extradited him and his co-defendants to face Enron-related US fraud charges even though nothing they were accused of looked like a crime under UK law, Britain was becoming ‘the 51st state of America’. Many Swiss citizens must have felt they were living in the 52nd when Department of Justice agents decided, as I put it in 2013, to ‘topple a whole bowling alley of gnomes of Zurich’ in an assault on Swiss banking secrecy that forced the closure of the country’s oldest bank, Wegelin. The catalogue of US fines imposed on non-US banks for money-laundering, sanctions-busting and market manipulation has added to the impression that Washington draws its own boundaries at will.

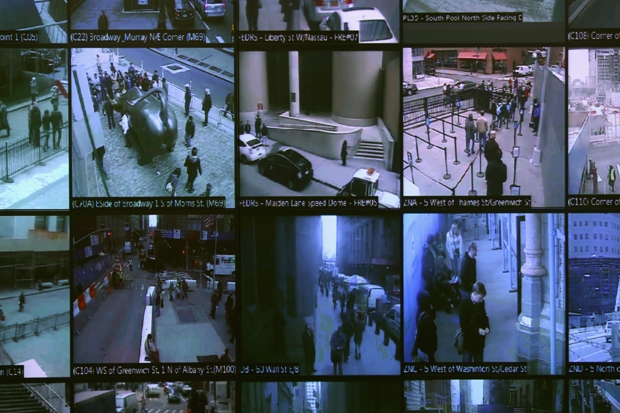

This long arm of US justice — sometimes, as I have observed, seeming to act as an instrument of US foreign policy, and unmatched by reciprocity for others chasing suspects on US soil — has been a troubling feature of world affairs ever since the Bush administration first started flexing muscles. It has become, in effect, the world’s CCTV system. When it operates intrusively outside US territory, we resent it as an infringement of national rights. When it captures wrongdoing to which other national and international authorities have been turning a blind eye, as seems to be the case with Fifa, we feel grateful that, in this respect at least, America is still the leader of the free world.

A global game

Football, like banking, is a global game — and the defence most frequently offered for overpaid bankers is that they are not as overpaid as footballers. In that sense, because football is such a potent focus of aspiration in poorer parts of the world, it is all the more important that the game should offer clean role models. And in the current Fifa case, it has been a pleasure to watch the United States attorney general, Loretta Lynch, elegantly blowing the lid off the stinking can of worms that the top echelon of the sport’s administration appears to have become.

Lynch was careful to assert that many of the allegedly corrupt schemes of the Fifa officials so far arrested were planned in meetings held in the US, and that US banking and ‘wire’ services were used to transmit bribes which arose from ‘promotional efforts directed at the growing US market for soccer’.

So not even the departing Fifa president Sepp Blatter has tried to suggest there is no US locus — though he did try to suggest a hidden foreign-policy motive when he said the timing of the arrests was an attempt to favour his presidential election rival Prince Ali bin al-Hussein of Jordan because ‘the United States is the main sponsor of the Hashemite Kingdom’.

It’s not surprising, given the level of media heat and continuing FBI scrutiny, that this leathery 79-year-old won’t have the chance to serve out his fifth term with dignity and throw a fancy farewell banquet at the end of it. But as he prepares to spend more time with his collection of match programmes, the real test of the effectiveness of the US intervention will be whether it provokes a reopening of the bidding process for the 2022 World Cup, which was controversially, indeed laughably, awarded to Qatar.

Apart from the issues of temperature for players (even if the tournament is now scheduled for November and December, disrupting the European football season) and human rights for visiting fans, it is apparent that the Gulf state can deliver barely sufficient stadiums, hotels, training camps and transport links on time only if an army of slave-waged workers from India and Nepal builds them under appalling conditions: 1,200 have already died, according to the International Trade Union Confederation. In Fifa’s own evaluation, Qatar’s bid was the only one of nine applicants to be judged ‘high risk’ — and the risk now is that a cleaned-up Fifa will be left with an indefensible legacy of the ancien régime.

Civilising influence

A salute to CivilisedBank — an online ‘challenger’ in the small and medium-sized business banking sector — not only for its eye-catching choice of name but also for its decision to make executives swear a ‘bankers’ oath’ akin to the Hippocratic oath of the medical profession.

You may recall that the think-tank ResPublica came up with the oath idea in a paper on ‘Virtuous Banking’ last year, and that, with the help of readers’ suggestions, not all facetious, I had a go at improving on what I felt was a worthy but wordy first draft. Civilised chiefs Chris Jolly, formerly of Merrill Lynch, and Gordon Dow from Santander, have set aside my simple idea of adopting the West Point Honor Code (‘A cadet will not lie, cheat, steal, or tolerate those who do’) and gone for the 222-word Full Monty from ResPublica, replete with phrases such as ‘I will do my utmost to behave in a manner that prioritises the needs of customers… I will confront profligacy and impropriety wherever I encounter it… I will remember that I remain a member of society.’ I still think it could have been snappier, but it’s certainly a gesture in the right direction.

Top pot stocks

Having read Jeremy Clarke’s column last week about ‘the perils of smoking superskunk’, I feel the least I can do to prepare for our forthcoming Spectator Cruise together is to research the rapidly growing market for marijuana shares. The weed is now legal in four US states (Alaska, Washington, Oregon and Colorado) as well as being widely available for ‘medical purposes’. Surveys suggest at least 7.6 million Americans spliff up (is that the expression?) every day of their lives. In what could become a $40 billion-a-year market, there are already dozens of ventures vying for investors’ attention: Google ‘Top Pot Stocks’ for a first whiff, but don’t blame me if you end up like Jeremy.

Comments