It would be natural to assume that sinking bond markets would be the government’s priority this week, as low UK growth and high borrowing rattles investors. Yet remarkably the Prime Minister’s attentions seem to be focused elsewhere: on advancing a deal to cede sovereignty of the Chagos Islands to Mauritius in the days before Donald Trump is inaugurated for his second term as US President. Trump is an opponent of the deal for good reason. The US military base on Diego Garcia proved invaluable during the two Gulf Wars.

Keir Starmer is yet to meet an international tribunal he won’t genuflect before

Keir Starmer, a former human rights lawyer, appears to be motivated by a desire to observe the rule of international law. Seven years ago the International Court of Justice delivered a ruling that Britain has an ‘obligation’ to end its administration of the Chagos Islands. The United Nations International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea has since ruled that the UK does not have sovereignty over the Chagos Islands. The genuine authority of these edicts is questionable but Starmer is yet to meet an international tribunal he won’t genuflect before. In his eyes, an arrangement by which Britain cedes sovereignty but then leases back its base on Diego Garcia for a term of 99 years is a way for the government to abide by the law while continuing to look after our defence interests.

It is true that the way in which the military base on Diego Garcia was set up in the 1960s was harsh, judged by the standards of today. The 1,800 residents of the Chagos Islands were removed, settling in Mauritius or Crawley in West Sussex. Medical facilities were closed and supply ships withdrawn to force them to leave. That these tactics were employed by Harold Wilson’s Labour government perhaps unsettles Starmer.

The government’s deal with Mauritius raises two important questions. First: should the non-binding rulings of international bodies really take precedence over national and global security? Second: what reason is there anyway to believe that the sovereignty of the Chagos Islands rightfully lies with Mauritius?

On the first point, the government’s deal is clearly damaging to the security of the West. The base on Diego Garcia was created as a means to counter Soviet power and influence in the Indian Ocean during the Cold War. It is not impossible that the base will be needed in future in the event of a conflict with Iran. Moreover, the deal will embolden an expansionist China, which Mauritius sees as an ally. Our potential enemies, needless to say, do not prioritise legal niceties over national interest – as Vladimir Putin has shown in Ukraine and Xi Jinping demonstrates in plans to extend China’s territory in the South China Sea. A 99-year lease on Diego Garcia might seem long enough, but so too did Britain’s lease of the same length for Hong Kong when it was first signed. The lease weakens Britain’s hold on the base, which the government of Mauritius may well seek to undermine further before the lease is up.

As for Mauritius’s claims to sovereignty over the Chagos Islands, they are tenuous. Colonial Britain did not in this case seize a land which was already occupied by others. The Chagos Islands were unpopulated when discovered by the Portuguese in the 16th century, after which they passed between European powers without ever having a native population. The people of Chagos removed from the islands in the 1960s were the descendents of slaves of other workers who were taken there to work on plantations. The islands never ‘belonged’ to Mauritius. Chagos and Mauritius were simply administered together as a unit by the British. When Mauritius was granted independence in 1968, the Chagos Islands were not part of the deal. So why the claim to sovereignty now?

It could be argued that the Chagos Islands should have had their own independence. But the French have no intention of ceding independence to their own Indian Ocean territory, Reunion Island, which became part of France in just the same way as the Chagos Islands became a British Overseas Territory. Will Starmer raise the matter with President Emmanuel Macron next time they meet? It’s unlikely.

Yet Starmer and Foreign Secretary David Lammy have behaved, over the Chagos deal, as if they are the defeated parties in a war, begging concessions from the victors. The original deal, negotiated in October, was bad enough, but the UK government then agreed to reopen talks with Mauritius’s new Prime Minister, Navin Ramgoolam, who has been demanding a huge increase on the agreed rent of £90 million a year – possibly as much as £800 million. Ramgoolam is also reported to want a shorter term of 50 years.

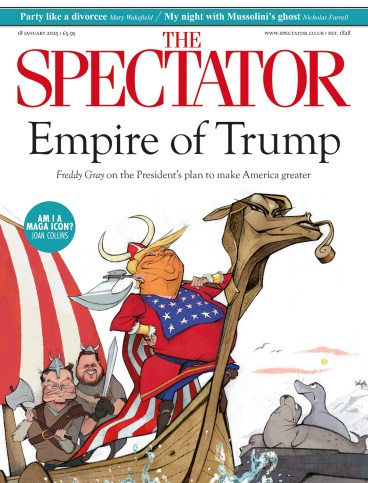

The story of Britain’s unnecessary and self-harming handover of the Chagos Islands marks the stark difference between our own Prime Minister and the incoming President of the United States. The former is a believer in human rights theology who lives by the rulings of international bodies, however unaccountable and politically motivated they may be. The latter is a muscular leader who will unashamedly put US strategic interests above the opinions of NGOs. It is hard not to conclude that in this respect the American people will be better served by their new leader than we are by ours.

Comments