Isn’t it irritating when your ancestral manuscript collection gets in the way of your ping-pong tournament? That was Colonel Butler-Bowden’s predicament in the early 1930s. He was so peeved by the heap of rubbishy papers cluttering up his games cupboard that he declared his intention to burn the lot. Luckily, his ping-pong companion that day happened to be a curator at the V&A, so the colonel was dissuaded from book- burning and his manuscripts were shipped instead to the museum’s London archives.

Among the collection was the unique edition of the Book of Margery Kempe, often described as the first autobiography in English, a sensational account of a woman’s mystical visions, travels and tribulations. For centuries, while her book hibernated in the Butler-Bowden estate, Kempe was completely unknown.

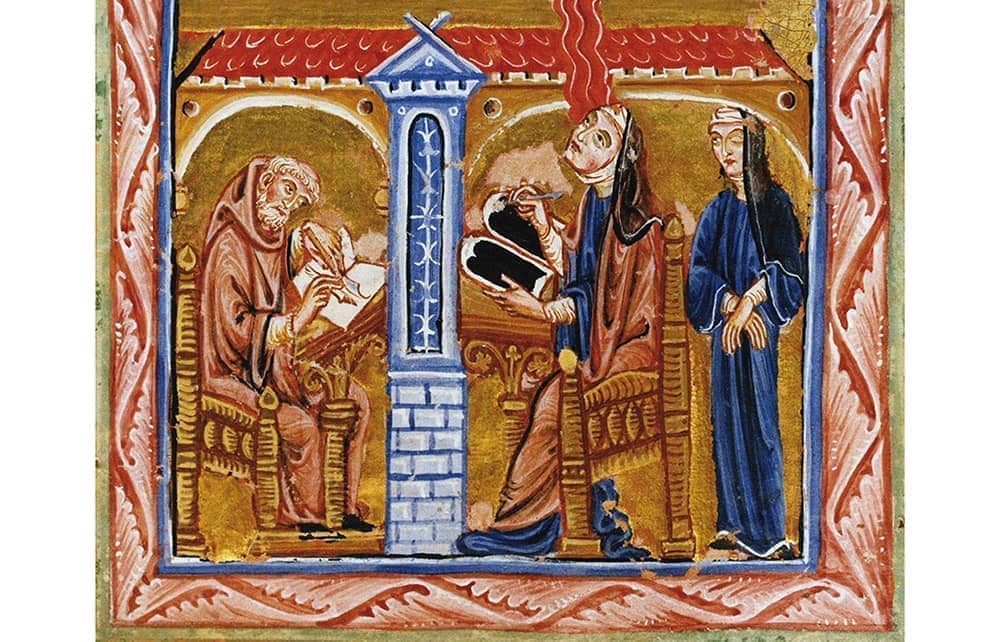

Janina Ramirez tells two significant stories here: the forgotten lives of medieval women and the scholars’ rediscovery of their records. She isn’t the first to describe the reappearance of Kempe’s extraordinary book, but she tells the story well, among many other catchy and varied examples. You might remember the Birka ‘warrior woman’ who went viral in 2017 after new DNA analysis revealed XX chromosomes in a Viking skeleton. But you might not be familiar with Margerete Kühn, who in 1948 crossed from recently partitioned East to West Berlin secretly carrying a priceless volume of the mystic Hildegard of Bingen’s writings.

Ramirez takes a broad scope both in time and geography, ranging from the 7th to the 15th centuries and crossing from East Anglia to the Rhineland to Krakow. Throughout, her history is led by new protagonists, from the Mercian Queen Aethelflaed (the daughter of Alfred the Great) to the anonymous embroiderers of the Bayeux Tapestry.

She emphasises the fragility of these histories, which – besides the general inclination of the past towards disintegration – have been subject to deliberate erasure. During the English Reformation, monastic libraries were catalogued, as the reformers made tricky decisions about which books to keep and which to destroy. The purging of libraries seems to have been a bureaucratic process, lacking the drama of iconoclastic mobs but no less chilling for being laborious. The title of Ramirez’s book derives from the label used during this classification process. ‘Femina’ indicated a woman’s authorship and signalled that a manuscript was not worth keeping. Given the importance Ramirez attaches to the label, it would have been satisfying to have had more details about this process and its results. For instance, how many books were marked ‘Femina’ – and did any survive, despite the hostile cataloguers’ efforts?

As Ramirez reminds us, there are real, immediate consequences to the way in which medieval history is told. From the Third Reich to the alt-right, the iconography of the Middle Ages has been used to give voice to white supremacist propaganda. Ramirez rejects this ‘misappropriation’ of history and offers up her cosmopolitan narratives of medieval women’s lives as an antidote. But she doesn’t fall into the trap of sanitising the past. Medieval racism and misogyny remain visible in her account, as seen from the perspective (mostly) of those affected.

You may be wondering what this book says about feminism. The author avoids using modern terms to describe medieval lives, so does not characterise the women in her history as proto-feminist heroines. However, she is clear that her project builds on the research of feminist scholars from the 19th century onwards, whose work has often been equally overlooked.

In her last chapter, she turns briefly to the marvellous example of Rykener, the person who presented variously as ‘Eleanor’ and ‘John’ and slept profitably around medieval Oxford and London until arrested in 1394. (I won’t spoil the full story if you don’t know it.) Do I wish there had been more about Rykener, or about the fluidity of medieval gender? A little, but not really. Ramirez asks us to see her book as a beginning. There are many who can take up those stories where she leaves off, and others have written on Rykener since the 1990s: head to Carolyn Dinshaw’s Getting Medieval for an in-depth account.

Which brings me to a general point about Femina. In many instances Ramirez retells episodes that, within a specialist field, are already well studied. Does that mean that her history isn’t ‘new’? I think the book still stands up to its subtitle’s claim. With such a range of characters there will be something new here for everyone. And it’s about time these stories had a wider audience. They’ve been waiting long enough.

Comments