Now that the Tory party has a mandate for change, it is refreshing to hear that Boris has committed more resources to the NHS and started to reverse some of the government’s blatant own goals, such as the nurses’ bursary cut. But the exponential increasing demand on the service, especially amongst people with more than one chronic condition, and its inability to fill at least 40,000 nursing posts, 10,000 GP positions and 40,000 consultant posts, means money alone will not solve the current impasse.

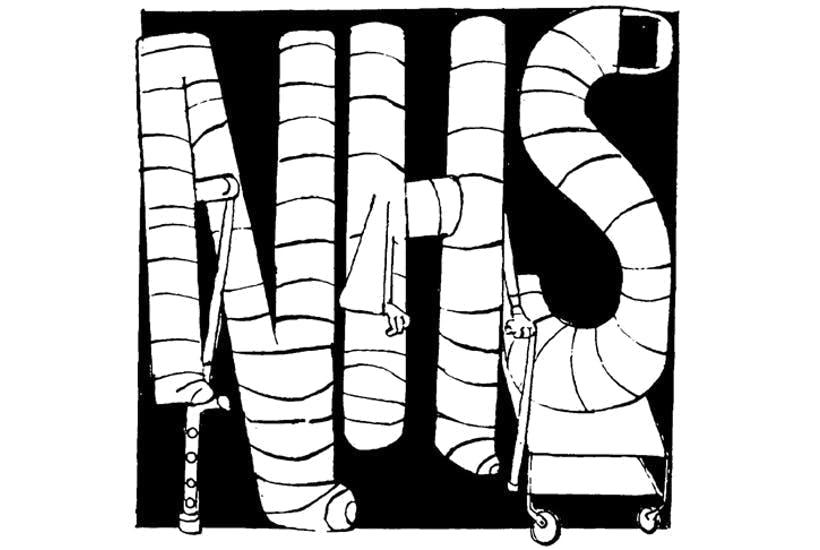

The main problem with the NHS is that it is treated like a religion and doesn’t suffer criticism well. And all attempts by politicians to improve it are doomed, unless the four major pillars on which it is currently tottering on are replaced with a more relevant structure, designed to withstand the ever increasing and changing demands placed on it.

The first of these pillars is the purchaser/provider split. Currently a regional panel commissions various services for its population, with hospitals and providers competing for ‘contracts’. The concept was designed to increase efficiency and keep costs down but has fallen foul of the law of unintended consequences, like so many other government initiatives. Multiple NHS hospitals now compete within their region for financially rewarding contracts, which leads to wasted resources, while there is a failure to provide services that are not deemed as rewarding. The managerial infrastructure that holds up the purchaser/provider system has been estimated to add an extra eight per cent of unnecessary costs to the health budget – an enormous amount of money that could instead support, for example, several new fully-staffed hospitals or over 300,000 nurses.

The second crumbling pillar is the private finance initiative (PFI), which was introduced by the Conservatives but embraced with gusto by Labour. It has led to up to £12 billion being borrowed to build hospitals and provide services, while incurring a cumulative cost to the tax payer of £97 billion over 20 odd years. At the end of each 20 year contract, the infrastructure, such as hospitals, will normally revert to the lenders. No sane person would ever have entered into any of these deals, either personally or commercially, especially when interest rates have been so low.

The third crumbling pillar is the absurd litigation structure that the government accepts. Patients are encouraged to sue for all kinds of unsatisfactory outcomes, often leading to large lump sum payouts for perceived errors of care, which can be in the millions. This outrageous situation was made worse when Liz Truss, as Lord Chancellor, increased the lump sums able to be claimed to compensate for low interest rates. Few people are aware of how badly this impacted the NHS’s finances.

At the time of the 2017 election there were £54 billion of outstanding claims on the NHS. Last year this had risen to £78 billion and this month, I am informed by the NHS confederation, it now stands at £85 billion. By next year, these obligations could equal the size of the entire annual NHS budget. Can something be done about this and is anybody at the NHS doing anything about it? The answers are yes, and no.

Australia had the same problem years ago and changed compensation liability so it covered severe negligence only, with no lump sum payments and any compensation paid monthly. Colleagues in Australia have benefited from year on year reductions in their insurance as claims have dropped to realistic levels, while in the UK we pay increasingly absurd sums of money for professional insurance to be protected from litigation. The rising cost of litigation is another reason GP numbers are falling and doctors are opting for early retirement.

The fourth and final collapsing pillar is the notion that a hierarchy of managers and chief executives without any healthcare experience can possibly manage this highly complex system. The very best hospital I ever worked in was run by a team of senior clinicians who oversaw a superb team of administrators in Australia. In the UK, management consultancy-driven organisation has led to hospitals being run by managers, with clinicians being used as the administrators. Many of these managers have no ‘coal face’ clinical experience and make poor decisions that have led to medical and other allied professions, such as nurses, being de-professionalised and made subject to constant email directives and bullying. This has led to a total collapse of morale amongst the profession with many taking early retirement, looking for other employment, or taking time off for work-related stress issues, thereby heaping even more work on the people remaining.

Meanwhile, many of my colleagues are no longer working the hours they otherwise might, because of Brown and Osborne’s ill-thought through tax and pension rule changes, which means consultants often have to pay to work extra hours. Between the two of them, the ex-Chancellors have done more damage to the NHS than the public will ever realise.

Unless these four broken pillars are replaced and dealt with, the NHS will sooner or later come crashing down, and be totally unable to provide the service that politicians promise. No amount of money thrown at the NHS will remedy these four crumbling pillars, which are self-evidently no longer able to hold up the NHS facade. Crucially, this is the point that all politicians to date have singularly failed to understand, presumably because they talk only to the ‘managers’ and not to senior clinicians.

Boris is in a unique position with a strong mandate to address these crumbling edifices, which are already leaving many people to die in ambulances and in the waiting rooms of overstretched emergency departments. Without such restructuring it will all get much, much worse. The start of a new Parliament and the strong mandate to do so is surely the best time to address this issue now.

Angus Dalgleish is professor of oncology at St George’s, University of London

Comments