One of the great unsung heroes of modern times is Lt Colonel Harald Jäger, an East German border guard who was the commanding officer at the Bornholmer Strasse checkpoint in central Berlin on that wondrous night of 9 November 1989.

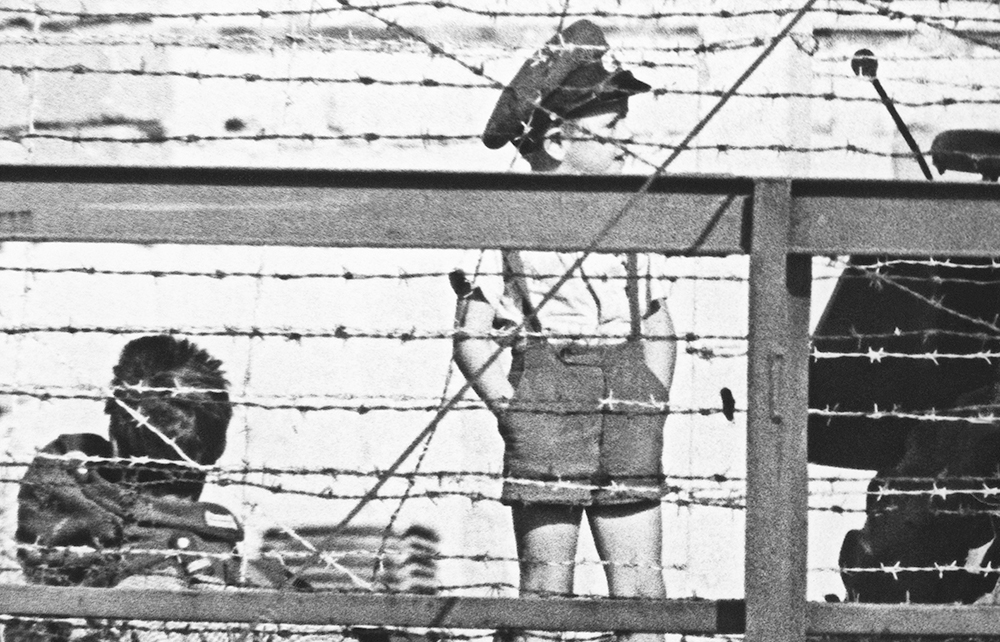

There are heart-rending stories of those who were shot ‘wall jumping’, the near-impossible method of escape

By 10.30 p.m., 20,000 people had massed in a narrow street, demanding to be allowed into the West, on the other side of the Wall – though at that crossing point the border was just a pair of gates. The mood was extraordinarily tense as the crowd became angrier. Whenever Jäger asked for instructions from his bosses in the Politburo or the higher brass in the army they panicked and told him to do nothing and wait. But things were too urgent. For the first time in his army life, I recall him telling me later, he disobeyed orders: ‘All I was concerned with was to avoid bloodshed. What if one of my men had shot, even in the air? I cannot imagine what might have happened.’ Entirely on his own, he decided to breach the Berlin Wall, ordered his men to open the red and white gates, and waved people through. The rest is history, which, despite some hype from a few liberal intellectuals in the following days, didn’t end that night.

Jäger is among a remarkable cast of characters – including top Communist party apparatchiks, dissident writers and priests, and workers – in this gripping narrative, full of vivid storytelling, about a deeply misunderstood place.

Katja Hoyer, now based in London, was born in the German Democratic Republic and was four years old when the Berlin Wall came down. Her parents had been born there, grew up there, bore children and built their lives there, and saw their country vanish almost overnight. She writes with passion and sympathy about a real place she knows and understands – not the one-dimensional Stasiland of grey monotony we in western Europe see depicted in movies:

Those with open eyes will find a world full of colour, not one of black and white. There were tears and anger, but also laughter and pride. The citizens of the GDR… worked and grew old. They went on holidays, made jokes about their politicians and raised their children.

Of course there was oppression and brutality in the most efficiently run police state in the Soviet world and Hoyer does not whitewash any of it. The GDR’s ruthless founder, Walter Ulbricht, who remained in charge for 25 years, was told by Stalin to make communist rule ‘look democratic, but ensure we hold the power’. Within a few years, all appearances of democracy disappeared, along with 120,000 opponents of the regime, in a series of purges.

Hoyer describes the key moments with brio, for example when Russian tanks suppressed a popular Berlin uprising in 1953 – a precursor to Budapest in 1956 and Prague in 1968. Describing the night in August 1961 when the Berlin Wall went up, she reminds us that a million and a half people, mostly the brightest and best, had fled the country the previous decade: ‘Entire cities were left without doctors.’ In the following pages, we read heart-rending stories of those who were shot ‘wall-jumping’ – as Berliners called the near-impossible method of escape.

By the time the ghastly Erich Honecker – a prime candidate for #MeToo complaints had they existed at the time – pushed Ulbricht out of power in 1970, the GDR’s failure was clear. The regime could feed people reasonably well by Soviet bloc standards through massive borrowing from western banks and dodgy deals, such as selling opposition-minded prisoners who wanted to leave the country to West Germany. By the time the GDR ceased to exist, the going rate for a dissident soul was more than US$ 100,000. In its last bankrupt years, Hoyer writes, ‘creating an illusion of progress became the principal state policy’.

But she is entirely right that there was more to East Germany than the Stasi, doped athletes and the Berlin Wall. Nowhere in the Eastern bloc, during the disastrous division in our continent imposed by the Soviets, were friendships, relationships and family as close and intense as in East Germany – as I know from personal experience as a journalist covering the region at the time. Hoyer has no nostalgia for the GDR, but she captures the intensity of daily living with deep perception in this balanced book – the best history yet written of the GDR.

Yes, she points out, there were around 500,000 regular informers working part time for the fearsome Stasi. As often as not what they didn’t tell their bosses was more important than the information they gave. And in the final analysis the Stasi were useless. They may have known what millions of people had for breakfast, but they couldn’t keep the Wall standing or save the state.

Comments